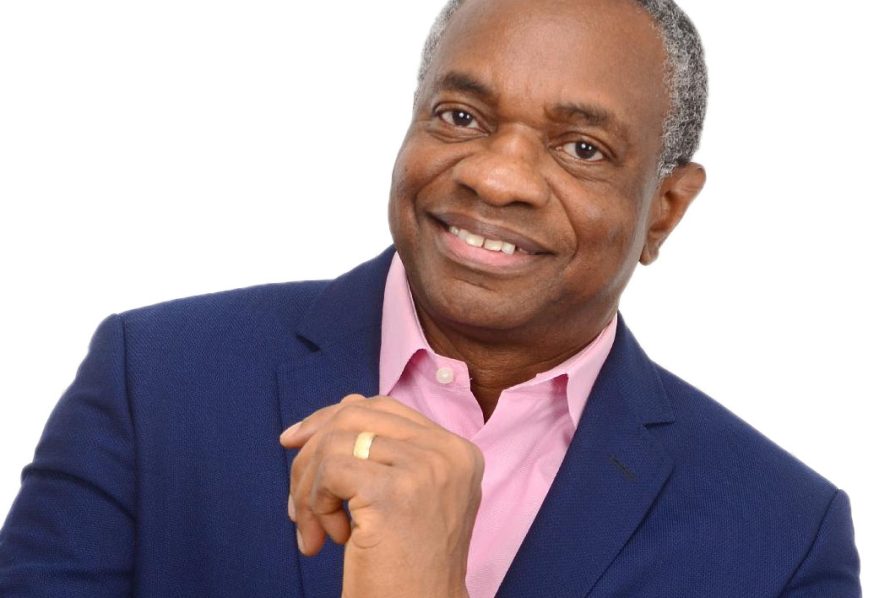

<strong>Dr. Udom Uko Inoyo retired as the Executive Vice Chairman of ExxonMobil Companies in Nigeria, in 2020, after a 31-year sojourn in the oil giant. With decades of experience in the oil sector under his belt, he makes a strong case for the deployment of technology to end oil theft in the country, as well as getting the refineries back to work. The former President/Chairman of the Council of the Chartered Institute of Personnel Management (CIPM) while insisting that the country must re-strategise to restore investors’ confidence and attract needed funds to exploit oil assets while fossil fuel remains relevant in the world economy. In this interview with ENO-ABASI SUNDAY, the Advisor to Inoyo Toro Foundation expressed regrets that most political leaders are not committed to education, adding that poor political leadership has trapped and created misery for the people. Inoyo also summarised his time at the international oil firm, spoke on the doctorate award recently bestowed on him by the University of Uyo, broached the issue of petrol subsidy removal, frequent coup d’états in Africa, Artificial Intelligence and technology-induced job losses, as well as stressed the need for Nigerians to be fiscally disciplined at corporate and personal levels.

It is obvious that Nigeria is not managing her oil fortunes well, as reflected in the massive and perennial theft of crude oil, the state of the country’s refineries, and the high pump price of petrol. Is crude oil constituting a problem for the nation now?

There is much to say here, but there is no need to rehearse what is already in the public domain. My only take is that we are collectively reaping what we have sown over the years: policy inconsistencies, mismanagement of resources, poor recruitment process, nepotism, and crass corruption. The blame can go around. However, if we genuinely want to reset, we must act right. Sounds complicated? No. Nigerians want the truth in all circumstances, which will engender effective followership. And there should be sanctions for policy violations or dishonest conduct. Take, for example, the status of the refineries.

If the Port Harcourt Refinery is to be fully functional in December, we need to trust the government. However, should it not be feasible, there must be consequences for those managing the refurbishment contract. In this era of technology, instead of constantly complaining about oil theft, the Presidency and NNPCL should use technology to address this problem by tracking criminality across international boundaries and prosecuting culprits. I know some international agencies and nations will support our efforts.

Security challenges in the Niger Delta have kept oil production low, robbing the country of increased forex. How much is the country’s inability to go beyond 1.4 million barrels per day (including condensate 1.7 million barrels per day) strangulating the nation’s economy?

Beyond the many sincere and intellectually driven opinions about how to stimulate the economy, even beyond oil and gas, given the centrality of foreign exchange earnings from the oil sector at a time of high price, it is painful that we cannot meet our OPEC target.

In the late 1990s, Mobil Producing Nigeria had plans to increase its daily oil production to 900 thousand barrels. Other IOCs did the same, leading NAPIMS to announce that by 2010, Nigeria was targeting two million barrels of daily production. Then, a series of events slipped in, including the government’s inability to fund its share of the expansion and operational costs. Thankfully, Dr. Ibe Kachikwu came on board as Minister of State for Petroleum and negotiated terms that persuaded the oil majors to reduce the amount owed to them for an amicable settlement. Though confidence was already severely shaken, there was a reprieve, and operations continued. What followed next? A new law, the Petroleum Industry Act, arrived at ‘curing’ all the oil industry’s challenges, including funding. So, what is the issue? If we have missed anything, what must be done to recover quickly? I remember vividly my interaction with senior government officials and bringing some of the concerns of the IOCs to their attention; the refrain was always dismissive- ‘The companies can go.’ Despite the active participation of several government agencies in crude oil lifting processes, the Federal Government turned around to accuse several IOCs of under-declaration of liftings worth hundreds of millions of dollars. Of course, some of the cases were discontinued after a review of relevant documentation to which the government had access.

Knowing how vital the sector is, Mr. President, as the Petroleum Minister, must re-strategise to restore investor confidence and attract the funds needed to exploit our rich oil assets within the timeframe that fossil fuel will remain relevant in the world economy. Any IOC seeking to divest should be allowed to do so. This would enable new players to come in and commence active drilling activities since the current players are no longer investing as expected. If you talk to any operator, I am sure they will admit that failure to do so creates an average of about 20 per cent production decline, and only an active work programme will stabilise or reverse such.

How wise a decision was it for the Federal Government to remove subsidy payment on petrol when none of the nation’s refineries was working?

There is never a good or bad time to do what is necessary. Subsidy removal was long overdue, and Mr. President did the right thing. Let’s focus on getting our refineries to work. And let us also be fiscally disciplined at corporate and personal levels.

As a former president of CIPM, what do you make of the quality of political leadership the country has had over the years?

I think we deserve the leaders that we have and should, therefore, not complain. As alluded to earlier, what is baffling is that we are happy to identify with top-tier clubs in the English Premiership but, at home, reject some of our best and brightest. In our business organisations, we ensure that capacity and competence are critical factors in hiring. Still, we come up with strange parameters for recruiting the leadership for the governance of a people seeking economic rescue. We are making no progress with such actions.

To what extent does the frequency of coup d’états in Africa point to the parlous state of governance on the continent, and how much of a curse do bad leaders constitute to the continent?

A military coup is neither a solution nor a political coup d’état desirable. But no one can disagree that poor leadership has trapped and created misery for the people. Efforts must, therefore, be made to change this through purposeful democratic governance. Regarding Nigeria, the next round of elections may be more problematic regarding voter apathy. That is not going to help us. One way to ensure public confidence in INEC is a public inquiry about what went wrong. That way, we can push forward with renewed hope.

Poorly resourced leaders have remained an albatross to the country and continent. Why is it difficult for African leaders to peer-review themselves, or at least learn lessons from the misfortunes of their contemporaries?

I doubt if member states of the African Union are rowing in the same direction. I also doubt if there is one African leader who is a shining example and respected by its citizens and within the continent. It is also difficult to point to an African leader who has built a good relationship with global leaders to champion such an initiative. Even if there was such an outstanding African leader, there is also the much-touted non-interference in the affairs of other African countries. We are collectively off the mark. Sadly, things are worsening.

Most corporate bodies now seem threatened by the unending departure of their tested hands to foreign lands. This development, known locally as Japa syndrome, is causing panic in the public and private sectors. Can this be a disincentive to national development in the long run?

Absolutely! Hiring good hands is challenging; losing such after a few years destabilises an organisation. And it worsens with an increase in the number of those leaving. But it is what it is, and organisations must rethink their operating models, focus more on training and technology utilisation, where applicable, and use the services of retired personnel, especially in critical areas. Gladly, remote work can lessen the disruption, but competitive remuneration may pose a challenge.

Artificial Intelligence and other science-based solutions to human challenges will eventually engender technology-induced job losses. Since we may not have control over these things, how do we mitigate the consequences if we cannot keep pace with the rest of the world?

Nigerians are intelligent and have the capacity to adjust to technological advancements. So, there is no need to be worried or offer excuses. Let me use this simple case to buttress my point. Last year, Mr. Ephraim Inyangudoh, a physics teacher in a rural public school in Akwa Ibom State and our foundation’s awardee for teaching excellence, became a United States Fulbright Teaching recipient. He arrived in the US and was exposed to new techniques in which he excelled. Now, he has a grant to train other teachers on applying creative imagination to innovate and invent machines to solve unique challenges. Talent abounds here just as technology is transferable. But in case anyone still debates the issue, such a person should reflect on what Alvin Toffler said more than 50 years ago in his futuristic book, Powershift: Knowledge, Wealth and Power at the Edge of the Twenty-first Century. Toffler wrote: ‘The illiterate of the 21st century will not be those who cannot read and write, but those who cannot learn, unlearn, and relearn.’

As past President of CIPM, how compelling is the need for government and private organisations to retool their workforce and equip them with the skills required in the new/evolving era to engender efficiency, speed, and improve service delivery?

This speaks directly to the quality of service delivery, and increased productivity, and, therefore, cannot be overemphasised. But I must also add that there is a cost to it, and where an employee is not adding value following such support, separation should be considered. There is no employment in perpetuity, especially where talents abound.

At the behest of the Presidency, between 2017 and 2019, you served as an examiner representing the private sector in appointing permanent secretaries in the Federal Civil Service. The Federal Civil Service (FCS) as the heartbeat of the government’s bureaucracy, many say, has been disappointing. What’s your assessment of the FCS and its contributions to national development?

Before answering your question, please allow me to make a little diversion: I do not know if many Nigerians are aware of the incredible investment of Mr. Aigboje Aig-Imoukhuede, the former managing director of Access Bank Plc., in transforming the Nigerian public service since 2017. If not, we should highlight them as he deserves our commendation.

My father retired as a permanent secretary, and I started my career as an administrative secretary. I know what the service was like in those days, but unfortunately, the quality has been diluted, and we are still paying for it. So, when I received a letter from Mrs. Winifred Oyo-Ita, the then HoS of the Federation, communicating my nomination by the Presidency to help in the interview process, I couldn’t turn it down.

Two things surprised me- the thorough interview process, which included a computer-based assessment, and the quality of the interviewees, all directors from different federation states for which vacancies existed. Given the thoroughness of the process, the candidates nominated were approved without any external intervention. That means our problem is not about capacity; these folks can competently take the initiative and drive national development. But there is an essential layer of concern- the political leadership. An often-tainted recruitment process of political leadership compromises operating a general interest, value-based public service sustainably.’

Last Saturday, the University of Uyo conferred on you, a Doctor of Law Honoris Causa as a result “of your track record of service to humanity, especially your credible contributions to education in Nigeria and beyond.” Does this honour impose on you any challenge going forward?

I don’t think it will pose a challenge, as my passion for philanthropy is aligned with my upbringing. We grew up cleaning the church premises on Saturdays, helping the elderly, and sharing with those in need, even though sometimes the latter was problematic when guests arrived while we were at the dining table. I am contented, and I don’t believe in too much wealth accumulation.

But I must confess that I was surprised that the university nominated me for the award, given that I am not currently in a position of authority, not holding a political office, and I do not know anyone in the university hierarchy. Nowadays, relationships are mainly transactional or based on a quid pro quo arrangement; to be identified for 16 years of private sector investment in education is much appreciated. However, the honour goes to the talented public school teachers who work under harsh conditions to shape the future of the next generation.

As the initiator of what is now arguably Nigeria’s longest-running teacher reward programme, how did your love for scholarship and professionalism contribute to the founding of the Inoyo Toro Foundation?

Perhaps I should indicate that my father started his career as a teacher. My family background exposed me to the pre-eminent position and often unappreciated role of teachers in our society.

While the love of education and the passion for excellence were the main drivers behind the founding of the foundation, the project would have collapsed without some key enablers. I always thank His Excellency Senator Godswill Akpabio, who, as the Governor of Akwa Ibom State, refused to buy into the blackmail of some government officials who misperceived this programme. Late Professor Ebong Willie Mbipom, as the pioneer chairman of the screening committee, did an excellent job bringing on board, committed members with integrity. Yinka Sanni of StanbicIBTC, and John Addey of Total gave us kick-off funds, and Mrs. Ntekpe Inoyo, my wife, who, while identifying with my passion, knew I had no resources to fund the project. She has been incredibly supportive over the years. We have been blessed with a professionally sound board, dedicated screening committee members, passionate mentors, and subject sponsors. Today, Savannah Energy is on board with additional programmes. However, I would be remiss not to state that most political stakeholders are not committed to education.

Many see the Ray Ekpu Awards for Investigative Journalism, which you instituted in honour of the beneficiary, as an attempt by you to turn an adversary into empowerment. What informed the award, and how did the onslaught against you in the local media contribute to its birth?

Well, both assertions are correct. I never knew Akwa Ibom State hosted such a high number of journalists or, in some cases, news peddlers. I was aware of the capacity for mainstreaming hearsay or ‘ebo-ete’ (they said…), but when I realised that some peddlers were on political actors’ payroll, I knew I was in trouble. They operated from unknown addresses and, even when identified, were not worthy of a libel lawsuit. I honoured an invitation from the Nigeria Union of Journalists, and the chairman, Amos Etuk, was very professional. I considered what best to do for the chapter and invested in immediate capacity training. However, I set up the award for sustainability in honour of a man of letters whom we all respect and call Uncle Ray.

You showed interest in governing Akwa Ibom State but got off the radar just before the election. What informed that decision or sudden loss of interest?

That engagement remains one of the best experiences of my life, as it also validated common fears about our brand of politics, which will be detailed in my memoir. But suffice it to say that when the state governor met with key political, religious, and traditional stakeholders and anointed his preferred candidate, it was needless to continue the journey, except one is a stranger to politics in a developing economy. Since service was my only consideration, I can offer the same outside of politics, as evidenced by our increasing intervention in the education sector.

Your long and rewarding career at ExxonMobil saw you rise to the apex of your career. What were the highlights of that sojourn?

My joining the company in 1989 was a proverbial case of preparation meeting opportunity. With a Political Science degree, I returned to study Law and was called to the Nigerian Bar in 1988. In 1989, I was notified that a company wanted a lawyer with an administration background, so I applied. When I joined the Human Resources function, I could understand why, and I opted to make a career of it, providing advice on employment and labour-related matters, driving policies and guidelines, recruiting, and compensation and Benefits. By 1998, I was on work assignments in the US and Belgium. In 2001, I returned to Nigeria and assumed the Human Resources Policy and Programmes Manager position. My next career move took me by surprise.

We had been working to identify a candidate to manage the External Affairs function, but the successful candidate turned down the offer at the last moment. Unknown to me, I had earlier been identified for this role, but my function, which gave me almost four years of exposure, was unwilling to release me. Now, at a critical juncture, the managing director stopped by my office to ask that we not proceed further with other candidates for the position. He offered me the position of General Manager, External Affairs, and membership of the Leadership Council.

Given the Niger Delta crises and resource control agitation by oil-producing states, this position had landmines embedded in it. I thought my background and contacts had given me enough exposure to dealing with the public and government. Still, nothing prepared me for the baptism of fire I would experience in that position.

Thankfully, things went well, and two years later, I was appointed Executive Director. By 2006, I became the In-country HR Manager/Executive Director and retired as the Executive Vice Chairman in 2020, spending thirty-one years with the company.

These service years were fulfilling despite occasional hiccups. I vividly recall my Day One onboarding process and the subsequent embarrassment I felt when escorted to my workstation and shown a box called a desktop. Coming from the Civil Service, where we had secretaries and typists, one was accustomed to writing in long hand that would be typed and printed out for signature. I was expected to do all my work by myself, including responding to emails. To quickly adjust, I befriended a colleague who had studied in the United Kingdom for immediate training. Though helpful, he never failed to extract a few bottles of Gulder beer and a plate of Isi-ewu each time we had a session.

After a few years, and as I became exposed to international opportunities, first with short overseas training and subsequently a work assignment, a significant challenge became breaking stereotypes about Nigerians. Generally, we are a great people, but sometimes, a few of us could conduct ourselves in a manner that typically creates a wrong impression about Nigerians. I needed to address behaviours such as tardiness, poor grooming, untidiness, lack of decorum, transparency deficit, etc. Not the hard stuff, but those things our parents and teachers taught us as we were growing up. I constantly reminded myself that the ‘self’ disappears quickly in an international audience, as one now represents the ‘us.’ So, there was no room for sloppiness. By 1996, I had my diary of the Simple things that matter and was always eager to share with friends and colleagues.

The hardest part of my work experience was when I got into leadership roles, mainly being unexpectedly appointed Executive Director in 2006. Of all the congratulatory messages I received, the most intentional yet confusing came from a senior colleague, Mr. Mathew Anuyah. He asked me: ‘to continue to be myself’ but added that I ‘must remember that the organisation that found me suitable for the position expected me to behave in a certain way.’ I met him later for clarification, and it was a matter of time before his counsel fully manifested. I had lost my freedom and now, viewed from the company’s lens, faced enormous pressure for conformity and excellence.

Leadership in a complex and transactional society is difficult, and it is worse when one works in a sector with historical scrutiny worldwide. The oil and gas industry is loathed by some and misunderstood by many. Sadly, even those who should know better, including government officials, find it politically convenient to blame the oil companies for the government’s negligence. We know that any foreign investor coming to Nigeria is attracted by the high return on investment (ROI). But there came a time when Nigeria started losing its place as an investment destination of choice, as investment funds were moved to other more profitable climes. The shareholders needed a more robust justification for investing in a country, which had refused to play by the rules and was owing vast sums of money without any certainty on payment timelines. On top of this was a deteriorating operational environment where vendors and employees were constantly being harassed by community members, including often distracting summons and inquisitions by government agencies. New taxes were introduced that impacted expected profits. Then, internal tensions with the workforce were almost calendarised.

When I became the Vice Chairman of ExxonMobil companies in Nigeria, and the communities, through the instrumentality of Chief Assam Assam, SAN, hosted me to a luncheon, I had cause to unburden my heart in my remarks titled The dilemma of an oil industry leader.’ Luckily, my good friend Osagie Okunbor, Country Chair of Shell, was in the audience, and he connected with my address.

If you wonder if I have regrets, let me assure you that I thoroughly enjoyed my career with a company that rewarded me handsomely in material terms and with opportunities that shaped my worldview. However, one major regret remains the conflict between company values and the dominant societal culture.

Working for an international organisation with best-practice operational models and strict rules was not a walk in the park. Regrettably, the expectation was that the same attitude of cutting corners, being nepotic, violating policies, and stealing would subsist here. Some employees, through pressure, got their fingers burnt, which hurt me as a Nigerian. But mark you, I have no sympathy for those who were deliberate in their violations. Looking back, I feel sad that actions that would in other climates earn people a badge of honour are repudiated here. Is it any surprise then that unethical acts are endemic in the country?