• Legislative expansion pushes projected deficit to N14.2 trillion

• Legislative expansion pushes projected deficit to N14.2 trillion

• Pressure to perform may push fiscal deficit to over N20 trillion

Except the country significantly doubles down on its revenue mobilisation capacity, perhaps well above 100 per cent, this year, the expanded 2025 budget revenue target could weaken the already fragile fiscal position of the Federal Government.

Among others, the speed of debt accumulation could increase, which could raise the burden of servicing over time even as the government would be more active in domestic debt accumulation and potentially crowd out the private sector operators.

Unfunded deficit, a new trend that was sparked by the funding drought in 2023, could worsen if the domestic and increasing credit-shy foreign markets are unable to provide give lifeline.

The gross domestic product (GDP) rebasing, when it is eventually implemented, could significantly reduce the current debt-to-GDP level and create a false borrowing headroom that would eventually increase the propensity to increase fresh loan applications by the government.

Nigerians, and indeed the market, had baulked at the government’s ability to meet the originally set N36.35 trillion revenue target, which was almost 100 per cent above the country’s most impressive performance.

In the first half of last year, even in the face of huge foreign exchange gain earnings, the Federal Government’s total retained revenue was N8.47 trillion – an impressive improvement from the previous record.

In 2023, the total revenue for budget funding available to fund the budget was N12.48 trillion. The government would need to triple its mobilisation capacity to close the gap between what it was able to raise then and what President Bola Tinubu plans to achieve this year.

The 2024 full-year report, understandably, is not ready as the budget is still being implemented (another new anomaly in the budgeting system). From the half-year report, the annualised retained revenue is N17 trillion, which is less than 50 per cent of this year’s target.

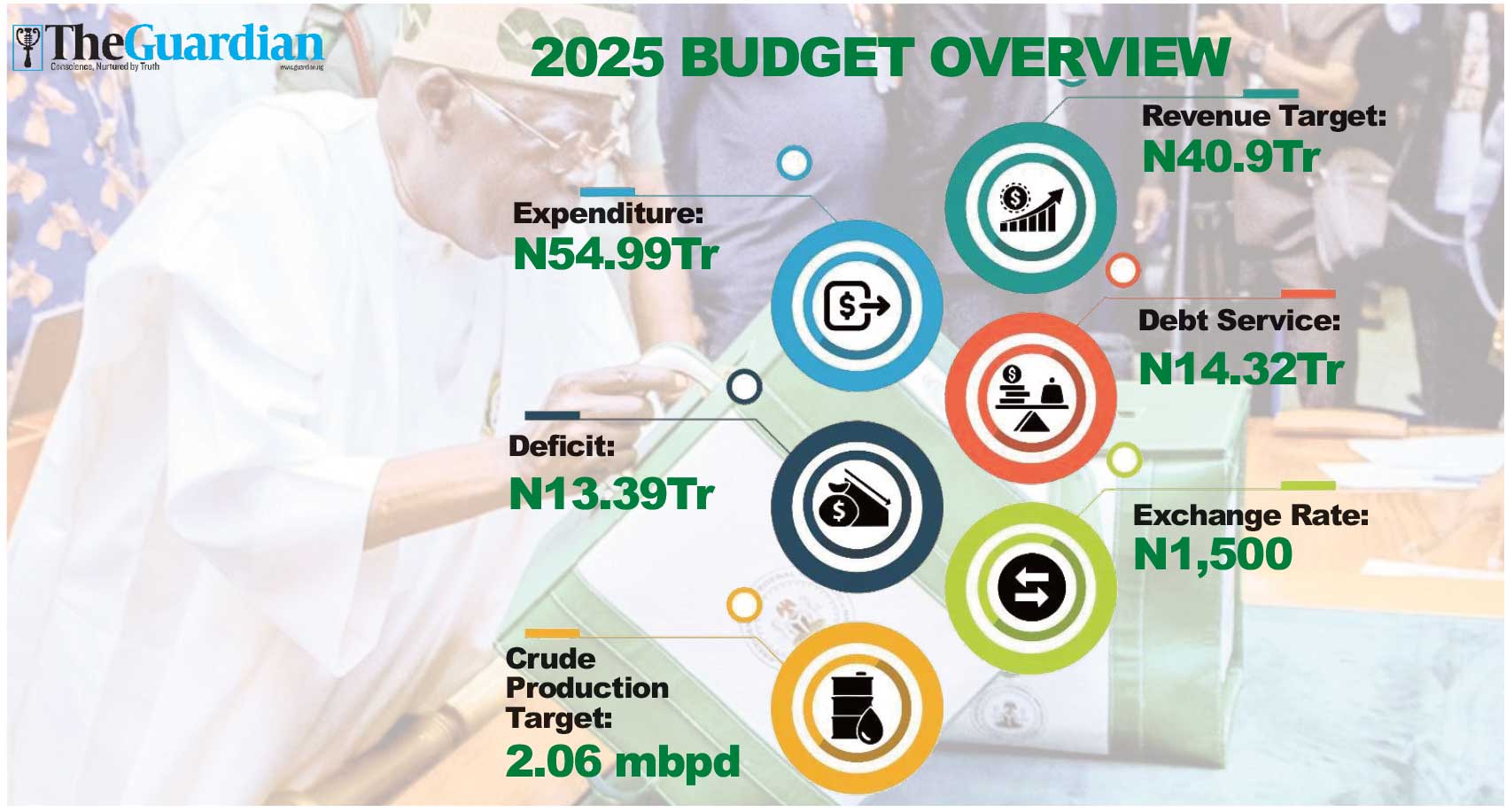

Leaning against widespread optimism, Tinubu wrote to the National Assembly while the budget was still under consideration informing the lawmakers of the potential growth in the expected revenue by N4.53 trillion, thus increasing the revenue side to N40.9 trillion.

The new target would be equal to the country’s best year (2023) stretched by nearly 300 per cent, which may be interpreted as an unreasonable target.

The current administration has embarked on new revenue drives and expanded tax programmes, anchored on overdue reforms, to raise public revenue. However, the reforms are stalled by political considerations; it is yet uncertain if the much-required implementation will take off this year.

If the reforms fail to secure legislative approval, the government’s desire to expand tax earnings to increase its revenue could remain a mere dream and restrain it to the old petrodollar source.

Sadly, crude earnings, as with other commodities whose prices are externally determined and influenced, are uncertain, especially with President Donald Trump’s America First campaign and all its trappings.

Still, the gross domestic product (GDP) data for last year as released last week says much about the foolery of depending on oil. For the first time in a while, the sector’s contribution to output buckled below five per cent, reinforcing the fear that crude, as the mainstay of the country’s public funding, has exceeded its peak and that it is retreating – a journey that is not particularly pleasant, whichever way it is considered.

If tax and crude fail the government, it could turn on more debts to fund its expanded programme, which the budget itself symbolises. For the first time, for instance, the proposed South-South Development Commission (SSDC), which is not significantly different from the Niger-Delta Development Commission (NDDC), was allocated N140 billion in anticipation of its take-off by lawmakers.

The expanded budget provisions for about N14.2 trillion deficits to be funded by new borrowings. But the figure could be much higher except the government bites the bullet – and reduces its expenditure. The projection is already much higher than last year’s number, going by the H1 report when the government reported N4.5 trillion and 2023 when it was N10.55 trillion (for the full year).

This year could see the government’s fiscal deficit pushing up to over N20 trillion, supposing the revenue projection stays at its historical average of 78 per cent performance. The government would be left with the option of running its expenditure as projected, leaving the deficit at the estimated N13.38 trillion (which Tinubu submitted) or 14.18 trillion (which the passed budget suggests).

In 2023, the revenue, for the first time, broke the target and recorded about 120 per cent performance. But 2023 was exceptional with front-loaded reform benefits such as subsidy removal revenue increase and exchange rate differential gains that came from FX market liberalisation.

With the normalisation of the economy, the government may not record such a spike in revenue inflow, a possibility that could push the performance of the revenue back into its historical average. Strapped of the 2023 boom, the five-year average performance is 68 per cent. In 2022, the government recorded 80 per cent, which was 10 percentage points higher than was recorded in 2021. In 2019 and 2020, actuals were 41 per cent and 35 per cent short of the targets respectively.

Interestingly, with the 2027 elections approaching, the government would be under pressure to spend (on both capital and recurrent items). This is a major case against achieving the much-needed fiscal consolidation to reduce fiscal rascality.

Except for political convenience, a strong point to call, the President may not be in a hurry to append his signature on the budget as there the supposed clean document is still riddled with contentious figures ‘smuggled’ into it during the legislative process.

Reports said an order paper containing the highlights of the passed budget suggested that the SSDC N140 billion even though the bill proposing its establishment is yet to be signed into law.

The media space is also awash with reports of allocation of the allocation of N400 billion to light rail projects in Lagos, Kaduna, Kano and Ogun states – projects that are the responsibilities of state governments.

The spending items were not captured in the original bills sent to the parliament for deliberation. Critics are already drawing the attention of the government to the anomaly, saying the fund should have been channelled to one of the many national rail projects that have stalled due to poor funding.

The Presidency may seek, according to findings, the cooperation of the lawmakers to expunge such allocations, a request that may delay the signing of the budget into law.

“In an extreme case, the budget would be returned to the National Assembly, which could mean extending the legislative cycle,” a source said.

The 2025 budget is meant to run from January to December 2025 after the implementation ceases. In the past few years, executions have extended by as much as over one year.

For instance, the capital component of the 2023 appropriation was extended three times and only ended on December 31, 2024.

The Guardian had reported that the 2025 budget implementation take-office date might be pushed beyond the traditional January 1 to the beginning of the second quarter.

With February ending this week, the government is in a race against time to start implementation of the budget on April 1.

Leveraging his cordial relationship with the lawmakers, the President could push necessary adjustments through in less than a week or less and sign the important fiscal document.

But the January to December implementation cycle may have been missed with the government now saddled with the responsibility of giving legal teeth to the new cycle going forward.

The Senate and House of Representatives had passed the bill over a week ago after it raised the spending envelope by about N5.3 trillion to increase the total sum to N54.99 trillion to the chagrin of millions of Nigerians who felt initial proposed N13.39 trillion deficit was ultra-high for a country that has been burdened by debts.

In the run-up to the legislative passage, Tinubu requested the National Assembly to raise the budget by an additional N4.53 trillion on account of an increase in revenue made by some government-owned agencies (GOEs), pushing the total expenditure to N54.2 trillion.

An increase in allocation to some spending channels by the lawmakers pushed the figure up higher to almost N54.99 trillion, a figure the President signed into law on Friday to the disappointment of those who felt the chief executive would seek further clearance on some grey areas.

Rather than reducing the original estimated 27 per cent deficit, both the executive and National Assembly opted to increase the number of spending items and the amount allocated to some.

The debt service provision was reduced from N16.33 trillion to N14.31 trillion – a moderation a presidential source said reflected the government’s improved fiscal position.

“That is progress. It means our fiscal position is getting better as a country. The President Tinubu administration has worked to rebalance the ratio of government revenue to debt servicing. We have moved from spending over 90 per cent of government revenue on debt servicing to 67 per cent. This gives the government better headroom to fund development priorities in education, healthcare, security, food security and critical economic infrastructure,” the aide said.

The source, however, declined to comment on the extent of consultation with the President by the leadership of the National Assembly before going ahead with the significant changes in the figures, directing The Guardian to respective authorities at the National Assembly who would neither comment on the issue.

Despite the N2.1 trillion mark-down in debt funding, the budget strained further away from the much-desired fiscal consolidation as the expenditure was raised in response to the perceived improved earnings as supposed to narrow the deficit gap towards achieving the desired black hole (debt brake) budgeting.

Significant last-minute legislative reviews pushed the deficit to over N14 trillion, from the initially estimated N13.39 trillion. The National Assembly increased the expenditure by N0.79 trillion without clearly articulating additional funding support. With the original N13.39 trillion, the deficit may have ballooned to N14.18 trillion.

But if the revenue projection, which the President, by his recent upward review, put at N40.9 trillion, underperforms, the fiscal deficit may be well over N14.2 trillion, which would further strain the fiscal position of the government.