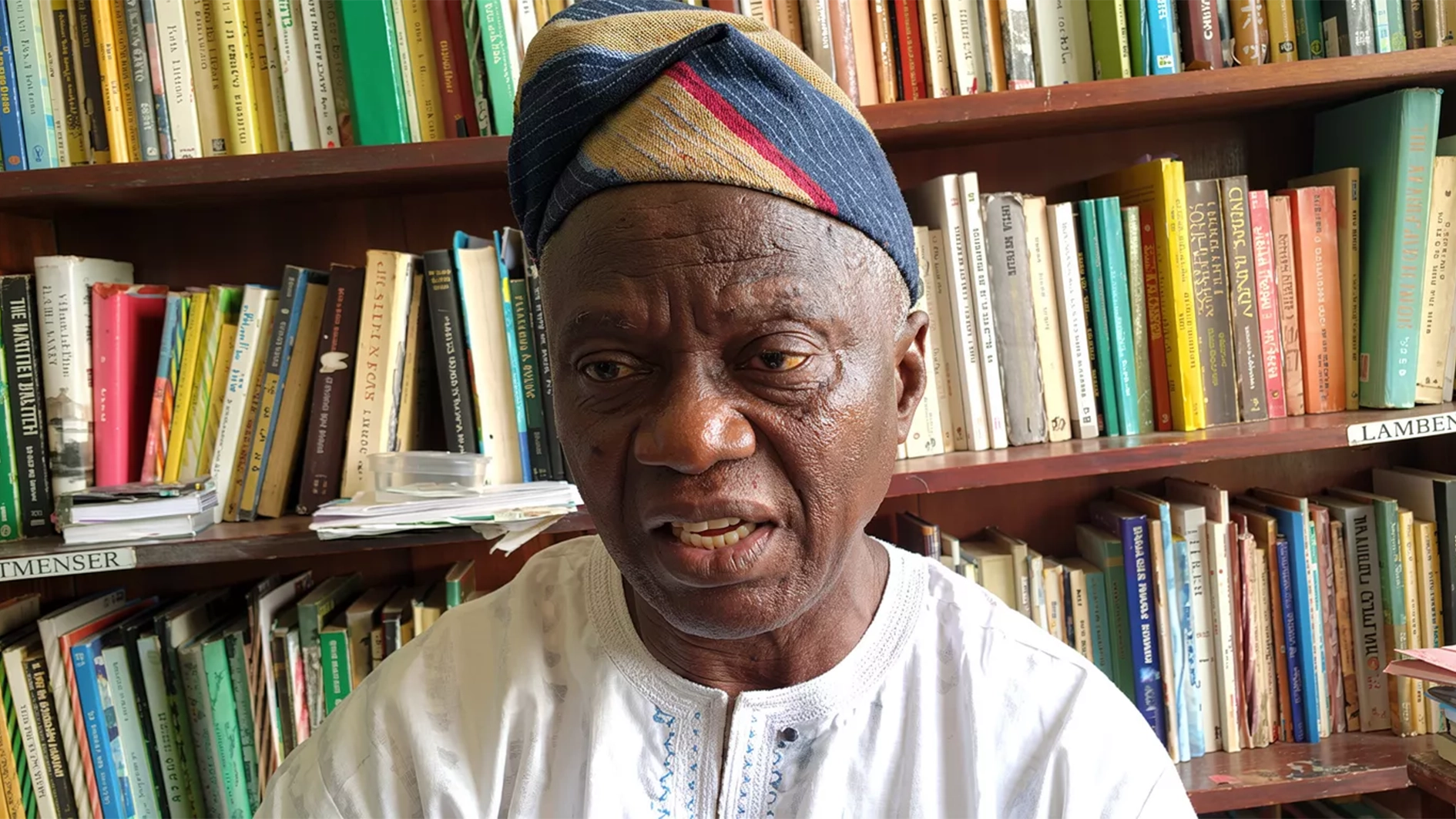

Dr Mustapha Abdul-Hamid is the President of the African Refiners and Distributors Association (ARDA). In an interview with KINGSLEY JEREMIAH, he raises concerns over continuous reliance on fuel importation across Africa amidst rising idle refineries and suggests solutions to funding regional infrastructure.

We have seen a trend across Africa where many refineries remain idle or underperforming. In Nigeria, for example, only a few are functioning while the state-owned assets are largely dormant. This seems to be a pattern across the continent. Are you concerned about this?

ABSOLUTELY. It is a major concern. One of the most effective pathways for Africa to make petroleum products more affordable and accessible to its citizens is by ramping up local refining capacity. That’s why the Executive Secretary of ARDA (African Refiners and Distributors Association) has consistently emphasised the mantra: ‘Refine or Die’.

However, the challenge lies in capacity; both technical and financial. Many African nations simply lack the financial muscle to install or upgrade refineries that can produce fuels meeting modern specifications. For instance, Ghana’s state refinery, the Tema Oil Refinery, was built in the early 1960s. The equipment is outdated, and despite Ghana now requiring fuels with a maximum of 50ppm (parts per million) sulphur content, the refinery cannot currently meet this specification.

During a recent visit to Nigeria’s OTL conference, I spoke with representatives from Crude Oil Refinery-owners Association of Nigeria (CORAN) and they raised the same concerns. They simply cannot afford the machinery necessary to refine cleaner fuels. This is not unique to Nigeria; Ghana faces the same problem.

That said, we found a temporary solution in Ghana. While our import specification is 50ppm, most of the imports we receive, largely from Rotterdam and Europe, are of even better quality, often around 10–15ppm, due to stricter European regulations. So, we have allowed the Tema Refinery to produce higher sulphur fuels, say, 1,500ppm and we then blend them with the low-sulphur imports. This blending process helps us meet the required specification overall.

Now, since the refinery produces higher-sulphur fuel at a lower cost but sells it at 50ppm market rates, they make a profit. The government then redirects that profit into a dedicated fund to finance machinery upgrades in the future. It’s not a perfect system, but it’s pragmatic. Other African nations could adopt a similar model while working toward long-term refinery upgrades.

Let’s talk about ARDA’s role in addressing the broader issues. Are there specific initiatives or achievements that you believe are already helping to close the supply gap and improve local energy markets, not just for petroleum but also for LPG and other products?

Certainly, ARDA’s ultimate goals align with Africa’s broader energy objectives of accessibility, affordability, and environmental sustainability.

Let us begin with affordability. ARDA has been advocating for regional trading using local currencies. Francophone West African countries already use the CFA franc, making energy trading more seamless. The anglophone bloc has discussed a common currency, the “Eco” but implementation has been slow. Nonetheless, using local currencies could reduce reliance on dollars, easing import costs and making energy more affordable.

On accessibility, infrastructure is key. We can’t talk about affordability without addressing infrastructure. As we’ve heard repeatedly, regional pipelines and distribution networks are critical. There’s already a West Africa Gas Pipeline, and recently we’ve seen moves toward a Central Africa Petroleum Pipeline. We could develop a continent-wide integrated petroleum infrastructure if we connect these regional networks in West, Central, East and Southern Africa.

ARDA has taken a bold step on clean cooking by launching a $1 billion LPG fund for Africa. We are working hard to raise those funds and have begun integrating clean cooking access into global energy dialogues. For instance, ARDA participated in the International Energy Agency’s Clean Cooking Forum in Paris last year.

This advocacy has led many member countries to begin prioritising clean cooking. In Ghana, for example, we’re shifting from the conventional “filling station model” where users refill cylinders to a “cylinder recirculation model” (CRM). Under CRM, users exchange empty cylinders for filled ones at safe, certified points rather than refilling directly. This improves safety and extends access to rural areas through mobile distribution using tricycles.

We have also seen international attention on carbon credits and reforestation, partly due to ARDA’s advocacy. A company based in Texas is now planting one billion trees in Ghana’s Volta Region. Our goal is to ensure every member country develops clear carbon credit policies, encouraging sustainable environmental practices while creating new revenue streams.

Beyond advocacy and technical support, is ARDA exploring new ways to fund other sectors beyond LPG, especially given that talking at conferences alone won’t solve the continent’s energy crisis?

That is a valid point. ARDA is, at its core, an advocacy and technical platform, not a political union. We’re made up of institutions that represent countries, such as Ghana’s National Petroleum Authority. These institutions are responsible for taking ARDA’s recommendations back to their governments and shaping national policy.

Fortunately, ARDA’s influence is growing. The African Union has now recognised ARDA as a strategic partner in its push for fuel specification harmonisation across the continent. This is a clear sign that our ‘barking’ is beginning to lead to real ‘biting’.

On global trade disruptions such as the policies of U.S. President Trump, which prioritised domestic interests, do you think there are lessons African governments can draw from that approach?

Absolutely. In fact, it is just common sense. Africa cannot develop if it remains a net exporter of raw materials and a net importer of refined products. We must begin to add value locally.

Take rice, for instance. Nigeria banned the importation of foreign rice and invested in local production. Today, it’s largely self-sufficient in rice. I often joke that if Ghanaian jollof is losing to Nigerian jollof, it’s probably because Nigerians are cooking with fresher, locally-produced rice while Ghana uses foreign rice.

The same applies to petroleum. Fuel prices remain high across Africa, largely due to two factors: currency depreciation and reliance on imports. Ghana alone spends about $400 million monthly to import fuel. Now, imagine the demand in Nigeria.

If we continue chasing dollars for imports, our local currencies will remain weak. This drives up the cost of fuel, which in turn raises prices across goods and services. The only way out is to boost local refining and reduce our import dependence.

With Dangote’s 650,000 bpd refinery expected to fully come onstream, there is hope. If it produces enough to meet Nigeria’s demand and exports to West Africa, it could reduce regional prices and help stabilise local currencies but the product must meet specifications to enter countries like Ghana.

Financing remains a critical issue. Are there out-of-the-box solutions ARDA is considering, like pooled investment mechanisms or sovereign wealth redirection?

That’s an excellent and timely question because, indeed, without innovative financing models, many of our dreams will remain just dreams.

At ARDA, we recognise that while advocacy, planning and technical assistance are important, they must be backed by real money. So yes, we’re increasingly looking beyond traditional funding sources. One of the key strategies we’re promoting is regional collaboration through pooled financing mechanisms. For instance, if several countries in a region agree on a shared infrastructure need like a regional LPG depot, pipeline, or refinery, they could jointly invest in it. This reduces the financial burden on any single country and also spreads the risk.

Sovereign wealth funds and national petroleum funds are also being looked at. Many African countries have resource-backed funds sitting idle or poorly managed. Redirecting a portion of these funds toward energy infrastructure, particularly projects that will create long-term economic returns, is something we believe in strongly.

We’re also working with multilateral development banks to design blended finance models where public funding de-risks projects enough to attract private capital. This is especially useful for clean cooking and LPG projects, which are essential but often underfunded.

Ultimately, the key is cooperation between countries working together, aligning policies, and recognising that regional integration can unlock financing opportunities that are simply not possible when acting alone.