Rumours, they say, travel faster even than the truth, but if they are not fact-checked early enough, they may become the truth. So is the story of suya in recent times. Many say it is dead animals; some say it is even human parts, which is why it is sold at night. But are these assumptions true?

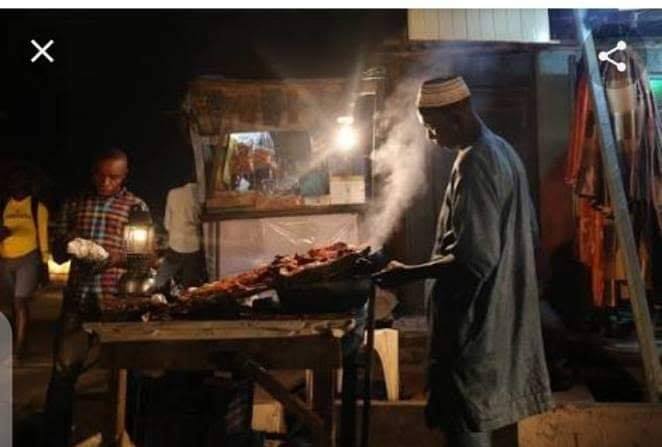

The sizzling sound of meat on charcoal, the sting of pepper in the air, and the sight of crowds clustering around makeshift wooden stands are familiar scenes across the city—from Surulere to Ojuelegba, Ikeja to Ajah.

Suya, the popular grilled meat delicacy originally from Northern Nigeria, has become a symbolic evening companion for Lagosians. But one question persists: why is it rarely sold during the day?

The Guardian journeyed to different joints and places where these delicacies are sold, and asked questions, but the reasons range from culture and climate to economics and psychology. In Lagos, suya is more than food; it is a nocturnal ritual.

Culture, climate and the pull of the night

The tradition of selling suya at night began with its roots. Originating from the Hausa people of Northern Nigeria, suya was typically consumed in the evenings after prayers or social gatherings. When Hausa migrants brought the practice to Lagos, they held on to the timing, even as the city’s character reshaped the business.

“Suya is an evening thing in our culture,” said Mohammed Garba, a mai suya operating in Ijesha under bridge in Surulere. “The way we prepare it, the way people eat it, it’s not fast food. People want to take their time.”

Climate also plays a role. The Lagos sun is harsh and unforgiving. Most vendors prepare the meat during the afternoon but wait for cooler evening temperatures before setting up their grills. The night offers the comfort needed for both the sellers and their customers.

“You can’t stand over hot charcoal at 1 p.m. under this sun,” said Ismaila Bala, who has been selling suya in Ikeja for nearly two decades. “Besides, people are not buying at that time. They’re at work or in traffic.”

Indeed, Lagosians spend a large part of the day navigating congested roads and busy schedules. It is only in the evening that the pace slows and people begin to seek moments of relaxation and something to eat.

Demand after dusk

For many Lagos residents, suya is not just food, it is a reward. After a long day of work or commuting, suya becomes the unofficial evening meal, often shared with friends or family.

“I don’t even think of suya until it’s night,” said Chiamaka Ogbonna, a UNILAG student. “It’s like a weekend thing or something you grab when hanging out. It’s not lunch food.”

This sentiment is also shared across the city. Whether bought on a Friday night after work or on the way home from a bar, suya has come to represent social bonding and end-of-day comfort.

Charles Effiong, a father of three, calls it a family tradition. “My dad used to buy suya on Friday nights. Now I do the same. It’s how we know the weekend has started.”

Beyond routine and sentiment, suya is part of Lagos nightlife in the marketplaces that include bars, lounges, roadside stalls, and night transport workers. The pairing of suya with drinks is particularly popular, and many mai suya intentionally set up shop near beer parlours or clubs.

“Suya and beer na brothers,” Garba said, as he attended to customers, sprinkling yaji (suya spice) over freshly grilled beef. “When people are drinking, they’ll always buy.”

Street food meets street life

The atmosphere surrounding suya is just as important as the meat itself. The streetlights, music blaring from nearby kiosks, and the smoky display of roasting meat all contribute to the suya experience. It’s a social event as much as a meal.

“You enjoy suya more when you’re standing by the fire, watching the man turn the sticks and slice the meat with that long knife,” said Frederick Ameh, a National Identification Number official, who had stopped at Ojuelegba’s popular suya joint. “That whole setup—you can’t replicate it at 2 p.m.”

The open-air model of suya selling relies on visibility and engagement. Customers often wait, chat, and even debate over who makes the best suya. Some argue that it is this relaxed street energy, absent during the hurried daytime hours, that makes suya special.

And while some restaurants now offer gourmet suya platters during lunch hours, many Lagosians find them inauthentic.

“I’ve eaten suya at a mall before,” said Kunle, a banker in Victoria Island. “But it wasn’t the same. Too clean, too organised. Suya is better when the seller hands it to you in an old newspaper.”

A ritual that may never change

Despite the changing food landscape and rise of online delivery services, the original suya sold under a dim bulb, on a Lagos street, after dark continues to thrive. It remains relatively affordable, widely accessible, and deeply rooted in both culture and city life.

“Even if you open suya shop by day, people no go come,” Garba said firmly. “They know say suya na night food.”

As night falls and the grills are lit across Lagos, the tradition continues. Flames rise, spices sizzle, and people gather—not just for a meal, but for something familiar, comforting, and uniquely Lagos.

Suya, it seems, is not just sold at night. It belongs to the night. And the various shared stories above bury rumours of the kind of meat people buy and the mai suya sells.