Between the 1970s and 1980s, music in Nigeria was not always a luxury or a jackpot when you had groups of military soldiers in your backyards always on alert. Back then, when critical music like Apala, Fuji, and Afrobeat was all over everywhere, before the Afro-pop of today, every day was like a war between military raids, arrests, and censorship for artists like Fela Kuti, Orlando Owoh, Chief Ebenizer Obeh, and co.

Particularly when I look back and see what Afrobeat is becoming, I wonder if we can still see a bit of what Fela did back then—the kind of crazy songs he sang and what he did with his music. Though it would be unfair to sideline Falz and Burna Boy, who have tried to sample his kind of songs, they still haven’t done a quarter of what Fela did.

However, this writer wasn’t born yet when those histories were made, but we learn from history, and stories like Afrobeat legend Fela Anikulapo Kuti can never be buried, because, like his name ‘Anikulapo’ implies, he holds death in his pocket.

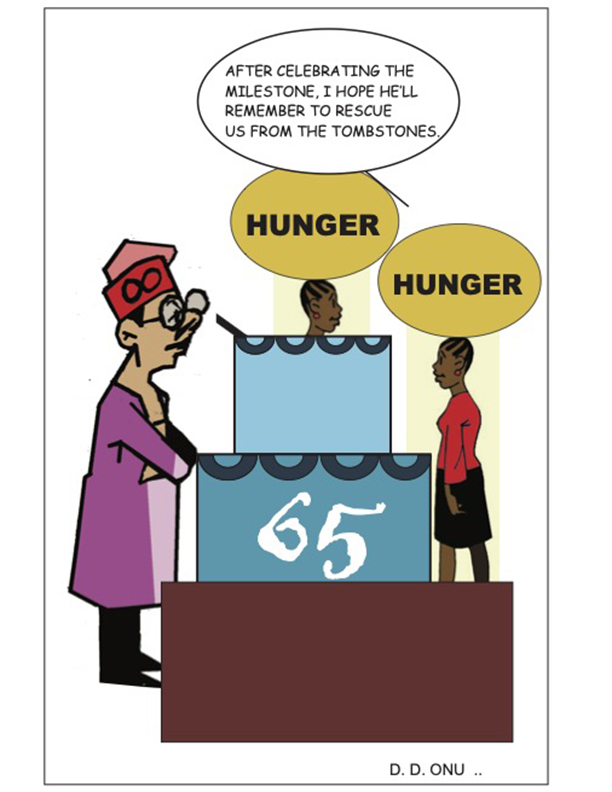

It’s been three decades now, yet Fela is still celebrated and glorified across several articles, documentaries, and publications. While some praise him as a genius, some critics condemned him because of how crazy he was with his revolutionary songs against his own country, which he saw as illegitimate—a testimony to the fact that postcolonial Nigeria is abysmal. Nigeria in this case has seen successive military coups, and there has been no change but to keep the oppressive state apparatus intact. Betrayal is what has compounded postcolonial Nigeria, and this was the betrayal that Fela pointed out with his Afrobeat, and such calling invited continued censorship, oppression, raids, and resistance.

When Fela Declared His Home an Independent Kalakuta Republic

What if it meant more than just a political theatre? Because like any great theatre, Kalakuta wasn’t just a place you went to watch. It was a place you went to become part of a movement.

Non-Agreement

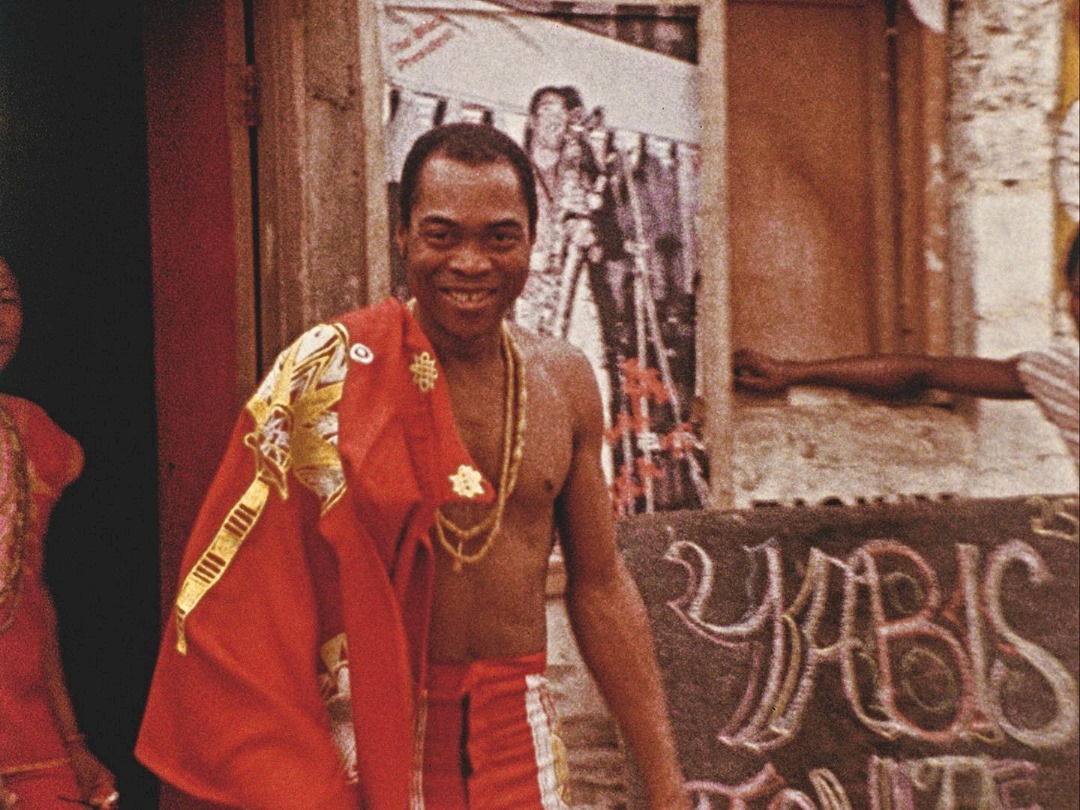

In 1970, upon his return from the United States, beyond his feel-good rhythm and spirit of highlife, Fela sought to create a space that idolised his ideals of freedom, unity, and self-determination. He named his compound “Kalakuta Republic,” an inspiration he got from a prison cell in “Kalakuta” where he had been detained.

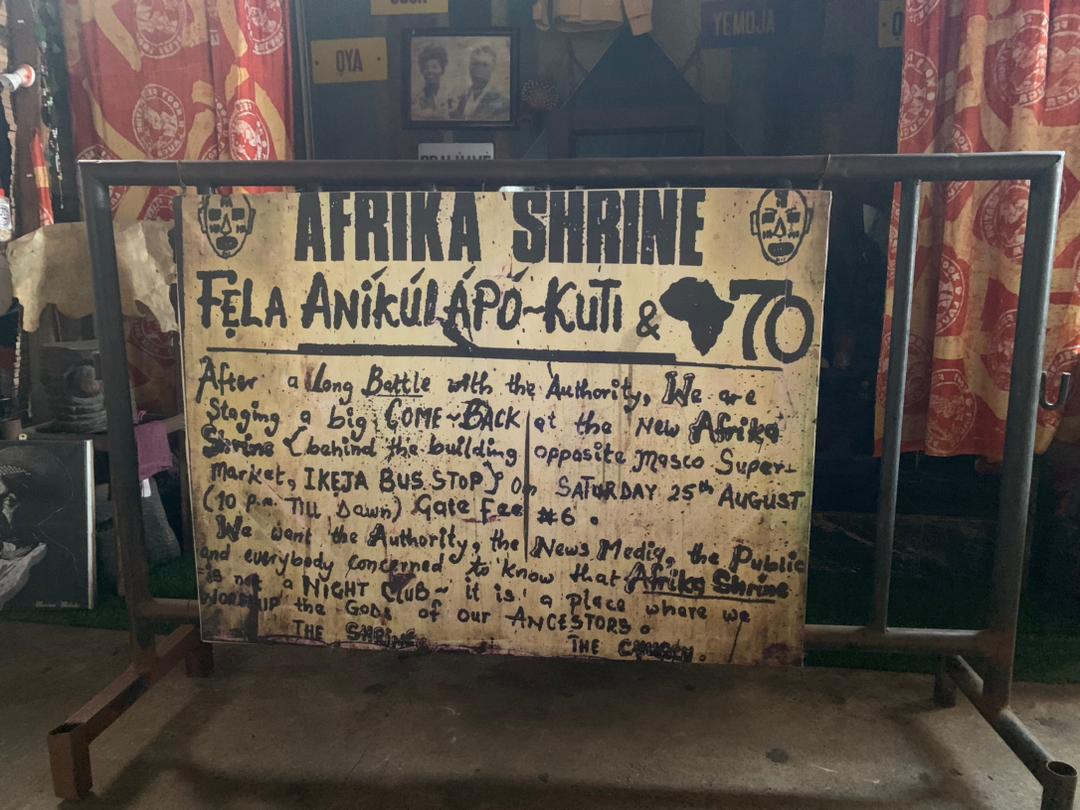

The term “Kalakuta” was said to be derived from the Yoruba word “kalakutu,” meaning “rascal,” symbolising how Fela’s republic should be projected—a place of rebellion and nonconformity. Situated around Agege Motor Road in the Mushin area of Lagos, the half-a-plot-size commune became a living space for his family, a recording studio for him and his band, a nightclub, and later known as the “Afrika Shrine” when he abandoned Christianity to embrace the African traditional religion.

Fela said, “I wanted to identify the ways of myself or someone who didn’t agree with that Federal Republic of Nigeria created by the British. I was in non-agreement.” At the time he made this statement, Kalakuta Republic had become his vision of an independent state—a place where he and his followers could live free from the tyranny of military rule, social constraints, and colonial hangovers. His declaration of Kalakuta as a “republic” was a firm stand against the “Federal Republic of Nigeria,” a country he believed was built on colonial foundations by the British.

No Space Belongs to Anyone

Beyond the political activism and revolutionary movement, Kalakuta was many things. Emmanuel Daraloye, an Afrobeat critic, describes Kalakuta as “a venue for the marginalised, a place where everyone could express themselves freely.” It was like a community for those who had no voice, a space where creativity flourished regardless of the oppressive forces surrounding it. “Kalakuta was a home for the outcasts, the misfits,” Daraloye adds, “a place where they could find purpose, unity, and purpose through music and art.”

“There are about 80 people or more living inside Kalakuta with Fela, and this house is just half a plot, but there is space everywhere. The place was so rowdy and crowded. Every space, you see people, but Fela would always say no space belongs to anybody,” says Lemi Ghariokwu, the artist who designed most of Fela’s album covers.

Kalakuta was like a half ghetto–half theatre. It was a place where anybody could walk in. It belonged to no one, although his mother, the late Olufunmilayo Ransome Kuti, owned the house.

One day, a boy came to see Fela and complained to him that his parents were hard on him. He had left home and had been sleeping on the streets. He asked Fela if he could come there. Fela said, “Okay, you can join. But nobody gets any space here,” Lemi Ghariokwu added.

From the frequent sex, mostly with ladies inside the Kalakuta compound, to smoking of weeds, gossiping, and yabing, these were part of the order of the day inside Kalakuta, which became part of Fela’s vision of a ‘radical freedom.’ Here, people lived as they wished, free to speak their minds and create without the threat of military harassment.

The daily rituals, the music itself, the worship, and entertainment were all part of his resistance movement inside Kalakuta. Everything he did in Kalakuta made his music become a weapon and made him less of an average human being—abami eda.

Kalakuta Queens and Yellow Fever

The Kalakuta girls, who are now famously called ‘Kalakuta Queens,’ were part of the many wonders in Kalakuta. They were part of what made the Kalakuta Republic an embodiment of mystery. The women were not only Fela’s partners but also active contributors to the commune’s artistic and political life. Against the widely known narrative that surrounds the inspiration behind Fela’s ‘Yellow Fever,’ the Kalakuta ladies were actually the ones who inspired the phrase.

On Lemi Ghariokwu’s account, “In 1976, when the military government set up traffic wardens, they used to be called ‘yellow fever.’ They gave the job to a colonel called Paul Tarfa to handle the traffic situation in Lagos in preparation for FESTAC 77. Tarfa came out with a rule that any offending driver caught should be dragged out of the car and given a bloody beating with Koboko. The day the traffic wardens were officially launched, some of Fela’s girls went to the market. When they got back to Kalakuta, they told Fela that those traffic wardens ‘don start again.’ They told Fela they saw the wardens, so he asked them to describe what they were wearing because Fela didn’t go out much. The girls said yellow fever.” That was how the phrase yellow fever came about.

“Some of those words that come out in Fela’s lyrics that have become national slogans sometimes come from the girls or the boys in the house because they are always high and they go out in the street,” says Lemi Ghariokwu.

Aside from the gossip, the Kalakuta ladies basically were Fela’s dancers, backup singers, and composers, who played pivotal roles in the creation of Afrobeat music and the performances at the Shrine. Later in 1978, in what was described to be a symbolic act of solidarity, Fela married 27 of his backup singers in a mass wedding as a response to the societal stigma and legal challenges faced by the women.

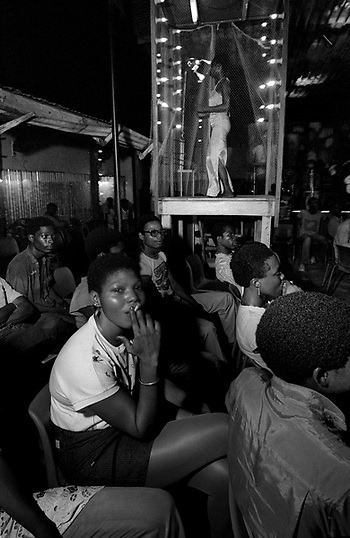

Yabis Night

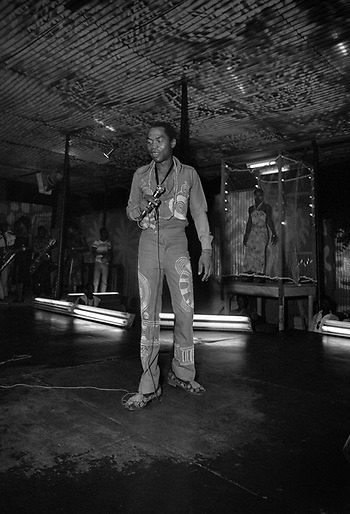

Three times a week, Fela would take to the stage, most notably on Yabis Night. Tuesday night was ladies’ night, so ladies were free, but their boyfriends would pay. “That’s why Fela got a lot of girls,” Lemi Ghariokwu said.

Yabis Night was a Friday event that attracted the largest crowds. Yabis, a term that eventually became embedded in the Nigerian lexicon, is Fela’s unique style of light-hearted sarcasm directed at serious issues. It is the night when people who were politically inclined would come to talk politics.

Fela would start by mocking himself, then his band, the audience, and lastly the government. Each show was a political act, where Fela’s sharp lyrics and infectious Afrobeat rhythms were intertwined with pointed social critiques. From mocking government inefficiency to celebrating the beauty of women in often explicit ways, Fela’s performances were a bold assertion of freedom in a time of oppression.

Saturday was a comprehensive show. That day would be a full show in the sense that he would have about 20 dancers doing choreography. Saturdays were also the day he did traditional worship. He would kill a chicken, pour libation, but he didn’t evangelise or force anyone to join him.

YAP News

Life within Kalakuta walls was also an embodiment of Pan-African ideals, discussions about African unity, and the collective struggle for freedom from the remnants of colonialism. This gave birth to the creation of the Young African Pioneers (YAP); however, its history is not well known or documented like other parts of life within Kalakuta.

When Ghanaian first president, Kwame Nkrumah, the acclaimed father of Pan-Africanism, wrote his books such as Africa Must Unite and The Challenge of the Congo, he was laying the foundation for what would later become Fela’s Young African Pioneers (YAP), a replica of Nkrumah’s Ghana Young Pioneers. Fela introduced the young boys in Kalakuta to many books, particularly those by Nkrumah, who was a real progressive Pan-Africanist, leading to the setting up of the YAP movement.

“I grew up in a place where everyone believed that Africa had to be free,” Kunle recalls. “There was a lot of Pan-Africanism. We were all learning, reading books, discussing how we could make Nigeria a better place.”

Lemi Ghariokwu, Durotimi Ikujenyo, and Kayode Mabinuori Idowu were the three founding members of Young African Pioneers. It was the inspiration they got from Nkrumah’s books that led them to introduce the idea of setting up the YAP movement. Fela embraced the

idea with the intention to start re-educating and brainwashing the young boys, and also to use that idea to replace the Boy Scouts, Guest Guides, Boys Brigade, and all other structures that the colonialists set up to brainwash Nigerians.

Gradually, YAP began to expand its scope to a broader umbrella. Its membership grew to about a thousand followers. At that time, Sunday Punch, which is today called Punch, was Fela’s most trusted news press, but with the birth of YAP News, it began its weekly newsletter column as a way to continue criticising the military government. “In 1977, Fela purchased a new printing machine worth $40,000 for his YAP News. Lemi Ghariokwu was the column designer and also designed the membership I.D. card,” said Lemi Ghariokwu.

One of the most controversial publications by YAP News was the real Fela’s FESTAC 77 nine-point proposal as a member of the committee, but he later renounced his participation when his proposal was not accepted. Major General Ibrahim Bata Malgwi Haruna, who was the head of the Nigerian National Participation Committee for FESTAC 77, discredited Fela’s proposal by claiming that Fela had requested that the government should ‘purchase new equipment for him,’ which Fela denied. It was believed that Pan-African ideas underscored Fela’s proposal. For example, his second point reads: ‘Specifically, the festival should attempt to re-educate the common man in Nigeria and Africa about the role of colonisation on African history and religion.’ It was believed that the Pan-African focus of Fela’s proposal might have been the basis for its rejection.

However, Young African Pioneers didn’t last for long. Things went into disarray after the 1977 inferno, when Fela’s home was burned to the ground by the military government. Within a year, YAP ceased to exist and metamorphosed into the Movement of the People (MOP) after Fela decided to run for the presidency.

1977 Inferno

A few days after the conclusion of FESTAC 77, the most singular event in Kalakuta happened. This was believed to be one of Fela’s darkest episodes and most documented moments in his music career, which ironically cemented the climax of his revolutionary movement against the military government. Perhaps, if this event hadn’t happened, Fela might not have been glorified or at least released those powerful jams like Coffin for Head of State.

On 18 February 1977, six days after FESTAC, about 1,000 military soldiers led by Major Daudu stormed Kalakuta, crippled his mother, and burnt the whole place to the ground.

In Fela’s biography by Carlos Moore, Fela described what the raid was like: “The soldiers were everywhere! They beat up the girls, raped some of them… They beat up my boys… They beat my brother, Dr. Beko, who was trying to protect my mother. They fractured his leg, his arm… Then, they grabbed my mother. And you know what they did to this seventy-seven-year-old woman, man? They threw her out of the window of the first floor. And me? Oh, man, I could hear my own bones being broken by the blows! Then, the whole Kalakuta Republic… went up in flames. The soldiers had set fire to the house.”

“I was conscious, like in my teen years, maybe 13 or 14 when they came. They came with tear gas unannounced. Once I started seeing tear gas flying, cannons of tear gas flying everywhere, then I knew they were here,” Kunle Kuti, Fela’s son, recalled.

The Kalakuta inferno epitomises Fela’s resistance against the military government and advocacy for justice. When his mother, Olufunmilayo Ransome Kuti, died a few months after the incident, Fela carried her coffin and took it to Dodan Military Barracks, which was the seat of military power during General Olusegun Obasanjo’s regime.

“It affected him deeply; it was a devastating time. But my father never gave up. He used the pain to fuel his music and his activism,” Kunle Kuti said.

A few months later, Fela released two songs: Sorrow, Tears and Blood and Coffin for Head of State, in which he sang frankly against how the military government killed his mother and how he carried her coffin to Dodan Barracks. Both songs criticised the social injustices, authoritarian violence, and oppression by the Nigerian government. After the destruction of the Kalakuta Republic, Fela had to move his shows to the Crossroads Hotel and made the Ikeja area of Lagos his new home.

Kalakuta Died

When Fela died in 1997, so too did Kalakuta. His death marked the end of the era of Kalakuta, though its legacy, hard to trace today, still continues through Fela’s sons, like Seun, Femi, Kunle, and grandson Made Kuti.

If Kalakuta were to exist today, it would undoubtedly look different. The rise of social media and digital platforms has given birth to a new kind of activism, one that is faster, more global, and more accessible. Today’s artists and activists have the opportunity to challenge authority in ways that Fela could only dream of. But, as Emmanuel Daraloye points out, “The consciousness level today is low. Artists are more focused on commercial success than political resistance.” The artists who claim to be inspired and motivated by Fela are nowhere to be found on the frontline of his advocacy.

Fela’s revolutionary spirit was not just about music; it was also about how he set up a republic that gave voice to the voiceless. Perhaps the most profound lesson from Kalakuta is that resistance is not just about music or art; it is about challenging the status quo, questioning authority, and never backing down, no matter the cost. Even in the face of death, Fela never backed down.

Kalakuta was more than just a stage or its physical structure. It was a blueprint for resistance, a place where music, politics, and everyday life married together to create one of the most famous and powerful movements that continues to challenge the oppressive Nigerian government.

After many years, it surprises me to see the same government that crucified Fela back then now on the frontline celebrating and immortalising his legacy. In 2012, the Lagos State government immortalised his last residence at 18 Gbemisola Street, Ikeja, Lagos, into a museum.

James, a freelance health journalist, is currently based in Adamawa State