At the moment, there are about 300 universities in Nigeria. As of early 2025, Nigeria has approximately 33 Federal Polytechnics, 60, State Polytechnics, and 27 Federal Colleges of Education, and 82 State Colleges of Education, plus some unspecified number of private Polytechnics and Colleges of Education. While the number of universities in Nigeria soars to 300, driven mainly by private institutions, experts have been warning that declining quality may threaten the future of higher education. This rapid expansion is largely driven by private universities, which now make up more than half of all institutions in the country. While this surge has broadened access to tertiary education, it has also raised serious concerns about the quality and sustainability of Nigeria’s tertiary institution system. Let’s take university education as the focal point here as most parents don’t want to introduce their children who are in Polytechnics and Colleges of Education. Specifically, federal and state governments have been upgrading Colleges of Education to Universities of Education – in this degree-crazy world.

In 1999, Nigeria had only 49 universities, including just a handful of private institutions. By 2025, the number has skyrocketed to 300, with 160 (53.3 percent) privately owned. The current landscape comprises 73 federal universities funded by the federal government, 67 state universities managed by state governments, and approximately 160 private universities. Federal universities have traditionally served as premier institutions focused on research and national development, while state universities provide regional access to higher education. The rapid growth of private universities, especially since the early 2000s, has been driven largely by soaring demand for tertiary education amid limited public capacity.

Although, the National Policy on Education, promotes the provision of equal access to educational opportunities for all citizens of the country at the primary, secondary and tertiary levels both inside and outside the formal school system; it states that for the philosophy of education to work harmoniously for Nigeria’s goals, education in Nigeria has to be tailored towards self realisation, right human relations, individual and national efficiency, effective citizenship, national consciousness, national unity as well as towards social, cultural, economic, political, scientific and technological progress.

To this end, some others have argued too that the Nigerian education system must be value-laden and tailored for the betterment of the citizens in order that they may live a better life and contribute to the advancement of society. For instance, some others have asked too: shouldn’t Nigeria be thinking about specialised universities in line with the agenda for the nation’s growth and development?

Meanwhile, while it is important to improve access to tertiary education, the issue of quality should be of concern to all. While there are good private universities, there are concerns that some of them have fallen short of expectation as their quality and standard of education have been markedly compromised. Some of the allegations levelled against the private universities include over inflation of unhealthy parallel grades to attract ‘customers’; inadequate funding; ownership interference, paucity of qualified teachers, among others.

Furthermore, there have been concerns on why NUC won’t take stock of the available manpower before approving more universities. There are reports that the number of lecturers available perhaps will only be adequate for about 40% of the existing universities in the country today. The implication of this is that even the resource verification carried out before approval of programmes, to a large extent, is merely ‘fulfilling righteousness’ because the name of one lecturer most often than not, appears on the list of lecturers for many private universities as an adjunct lecturer, some of which are in states that are very far from where the lecturer is working on full time. This raises questions about the frequency and quality of teaching that such an adjunct lecturer offers.

Many experts and academics have been warning therefore, that for a nation that is serious about its own sustenance and improvement, it should constantly look in the direction of the quality of its tertiary education, not just more institutions of higher learning, as some concerned citizens have posited. This situation calls for urgent action, because the situation is even more terrifying with obvious misplacement of priorities and celebration of mediocrity pushing the country’s education to the edge of a precipice. Something must be done now or else in the future, pundits will be trying to understand how Nigeria became, to use the words of our only Nobel laureate, Professor Wole Soyinka, “at best, yet another failed state, (and) at worst, an overcrowded necropolis where the hope of the future lies interred in unmarked graves.”

The points at issue on more or better tertiary educational institutions

Since 2016, I too have been writing and calling on senior and notable citizens, including those that had enjoyed ‘the good old days’ in this same country when universities were universities to support a motion that governments at all levels should stop all priority projects and declare emergency on education with a view to funding them ruthlessly. Specifically, I have won awards on articles written to support suggestions that there should be better and not more universities.

Where do we go from where Wole Soyinka once lamented?

I have been talking to the ideals on how to get to where we need to be in 21st century where education is fast changing the dynamics of development. The policy experts and scholars here and all of us need to understand that founding and funding a university isn’t for the fainthearted. Visitors who hold the fort for public universities constantly claim that they don’t have enough to fund education the way we want it in this same 21st century. In other words, if we look into the seeds of our education development times, what we will see now is that the education sector at home isn’t good and governments are only declaring emergencies whenever they want to hold general elections. We are talking at a time when most education leaders are again suggesting policies that will take us to where we can internationalise higher education again. That was the conclusion of my convocation lecture at the Adekunle Ajasin Univesity, Akungba, Ondo State in December 2023.

What is the real purpose of higher education for all citizens?

But let’s reflect on this classic to illustrate why demand for higher education should be more interesting to parents and leaders. According to Gasset (2005) on the Mission of the University. Why University Must Be Primarily: the University; Profession and Science. This is important for our leaders, policy makers and university owners.

(A) The university consists, primarily and basically of higher education which the ordinary man should receive.

(B) It is necessary to make this ordinary man first of all, a cultured person: to put him at the height of the times. It follows then that the primary function of the university is to teach the great cultural discipline namely:

1. The physical scheme of the world (Physics)

2. The fundamental themes of organic life (Biology)

3.The historical process of the human species (History)

4.The structure and functioning of social life (Sociology)

5 The Plan of the universe (Philosophy)

(C) It is necessary to make the ordinary man a good professional. Besides his apprenticeship to culture, the university will teach him, by the most economical, direct and efficacious procedures intellect can devise, to be a good doctor, a good judge, a good teacher of mathematics or of history.

The specific character of this professional teaching must be set aside, however for further discussion. So, whether it is local or ‘glocal’, the university should be equipped enough to play its primary role of turning the ordinary man to be what he wants to be: a professional. But can our tertiary institutions play this role today in this age of digital technologies?

Let’s look at the expediency of quantity too: we need more but qualitative tertiary institutions too…

I have consistently criticised my state for having four apparently ill-equipped universities at the moment. But then a recent survey has taught me some lessons that we need more universities, after all. Most of the universities in Nigeria always have enough students at all times. We are more than 200 million at the moment with about 300 universities. Let’s look at the population of our students in secondary schools seeking admission at all times.

#WAEC Statistics

A total of 1,973,253 SS3 students sat for this year’s May/June West African Senior School Certificate Examinations (WASSCE), which began on Thursday, April 24, 2025, nationwide. The students are from 23, 554 government and approved private secondary schools across the country.

# NECO Statistics:

Total candidates: 1,367,210 registered for the 2025 SSCE: 685,551 candidates are male while 681, 300 are female

JAMB/UTME Statistics:

Out of the 1, 957,000 million candidates who sat for the 2025 UTME, a staggering 1.3 million, roughly 70.7%, failed to hit the 200-mark threshold, according to new data released by the examination body. Only 565,988 candidates, or 29.3%, scored above 200, while a mere 6% managed to cross the 250-point mark.

Meanwhile, out of the about two million candidates that always apply for admissions only about 30% get admission organically in the end every year. In other words, despite all the alleged proliferations, all the 300 universities in the country are at this time of the year under pressure for admissions, especially for certain professional courses, notably Medicine and Surgery, Law, Nursing, Computer Science, Engineering, Accounting, Media studies, et cetera.

We need more, after all

That is why it is quite tricky to conclude that we don’t need more universities in Nigeria. Let’s turn to a avery prosperous Asian country Japan to deepen our understanding of why we need to do a different kind of restructuring and in fact a renewing of our mind about quantity and quality of tertiary education in Africa’s most populous country and hope of the black race.

Universities in Japan

The current population of Japan is 122,944,755 as of Sunday, September 28, 2025, based on Worldometer’s elaboration of the latest United Nations data..

But there are 1, 116 universities in Japan. Tokyo, the capital alone has 148 universities. Nigeria’s capital, Abuja has only six (6) as the seventh (7th) one captured in a databank, Bingham University is actually in Nasarawa State, near Abuja.

The number of private institutions in Japan is greater, as there are currently 86 national, 101 public, and 620 private undergraduate level universities, and 14 public and 295 private junior colleges.

Talking about the quality of their universities in Japan too, promoters make this claim:

Japanese universities do not follow trends — they set them.

It is here where the world’s most advanced laboratories are located, revolutionary discoveries are being made at local universities, and the quality of Japanese products, equipment and training is renowned around the world.

For many years, the Land of the Rising Sun was closed to foreigners, but at the end of the 19th century the doors of the majority of Japanese universities were opened for young people who plan to connect their lives with advanced technologies, innovative developments and science…

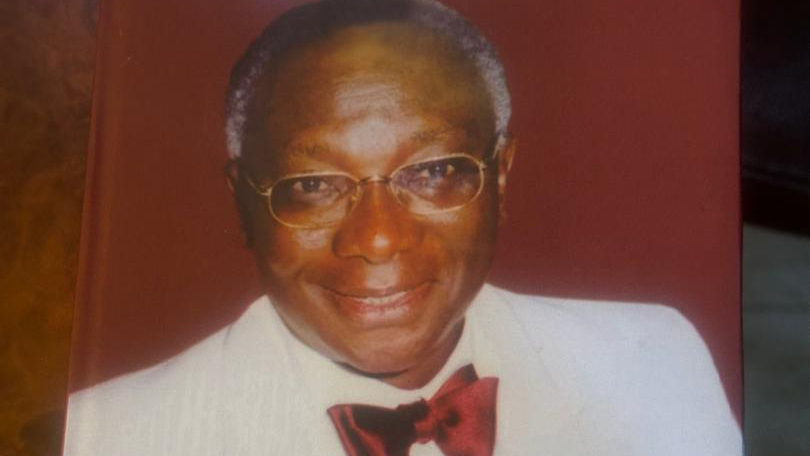

This is an excerpt from a 13, 884 page lecture Titled: “Do we need more or better tertiary educational institutions in Nigeria?” at the Ekiti State University 2025 Registry Annual Lecture/Award on October 16 by MARTINS OLOJA…

To be continued