Across Africa, the fight against terrorism has often relied on guns, raids, and rhetoric. From Mali to Mozambique, Sudan to South Sudan, and across the Sahel to the Horn of Africa, security forces are heavily focused on kinetic responses and brute force.

However, after every conflict, peace remains fragile, and violent extremism tends to resurface. This underscores the need for Africa to invest equally in social reintegration alongside military strength. As the African Union (AU) promotes its Agenda 2063 vision for a peaceful and prosperous continent, it faces a crucial realisation that Africa’s battle against terror cannot be won by force alone.

In Northeast Nigeria, where Boko Haram’s decade-long insurgency has left deep scars, a small but significant experiment offers a glimmer of hope.

The initiative, known as the “two-ratio-one” (2:1) model, reimagines counterterrorism as a process of restoration. Under this model, each rehabilitated ex-insurgent is paired with two victims who receive equivalent livelihood support at the point of community reintegration. It is a simple but powerful idea that signals a moral shift from punishment and neglect towards repair.

The approach acknowledges that the pain of victims and the transformation of offenders are two sides of the same coin. While it has inspired cautious optimism, it has also stirred controversy. Many victims perceive it as unfair that perpetrators receive state assistance while those they harmed remain forgotten. Uneven application of the program and perceptions of favouritism have deepened mistrust in some communities as well.

These tensions expose a flaw at the heart of many African counterterrorism efforts- an overreliance on militarism, symbolism, and material incentives with too little attention to justice, healing, and dignity.

Reconciliation cannot be transactional. True reintegration requires transparency, community participation, and sustained psychosocial support.

A sewing machine or a farming kit may offer income, but it cannot erase years of displacement, loss, or trauma. Many victims carry invisible wounds that demand counselling, legal aid, and emotional care. Without these, livelihood programs risk appearing as shallow compensation for unbearable suffering.

The 2:1 model also highlights the importance of social contact and cooperation. Empowering victims and ex-fighters separately may reduce hostility temporarily, but it does not build trust. Social psychology teaches that prejudice declines when people work together as equals toward shared goals. Community projects, cooperative ventures, and joint cultural initiatives can create common ground for recovery. In this sense, reintegration is not only an economic process but also deeply social and moral.

If refined, the 2:1 approach could help Africa rethink its broader counterterrorism frameworks. A new vision would rest on six guiding principles. First, humanise security by treating justice and rehabilitation as dual responsibilities of the state. Second, make victim inclusion transparent and non-negotiable. Third, promote cooperation between victims and returning fighters through shared projects. Fourth, make psychosocial healing (counselling, memorials, and trauma care) a core element of recovery. Fifth, anchor reintegration on fairness and accountability so that mercy does not become impunity.

Finally, regional institutions such as the African Union (AU) and the Economic Community for West African States (ECOWAS) should support local innovations, share lessons, and adapt successful models across contexts while respecting community ownership.

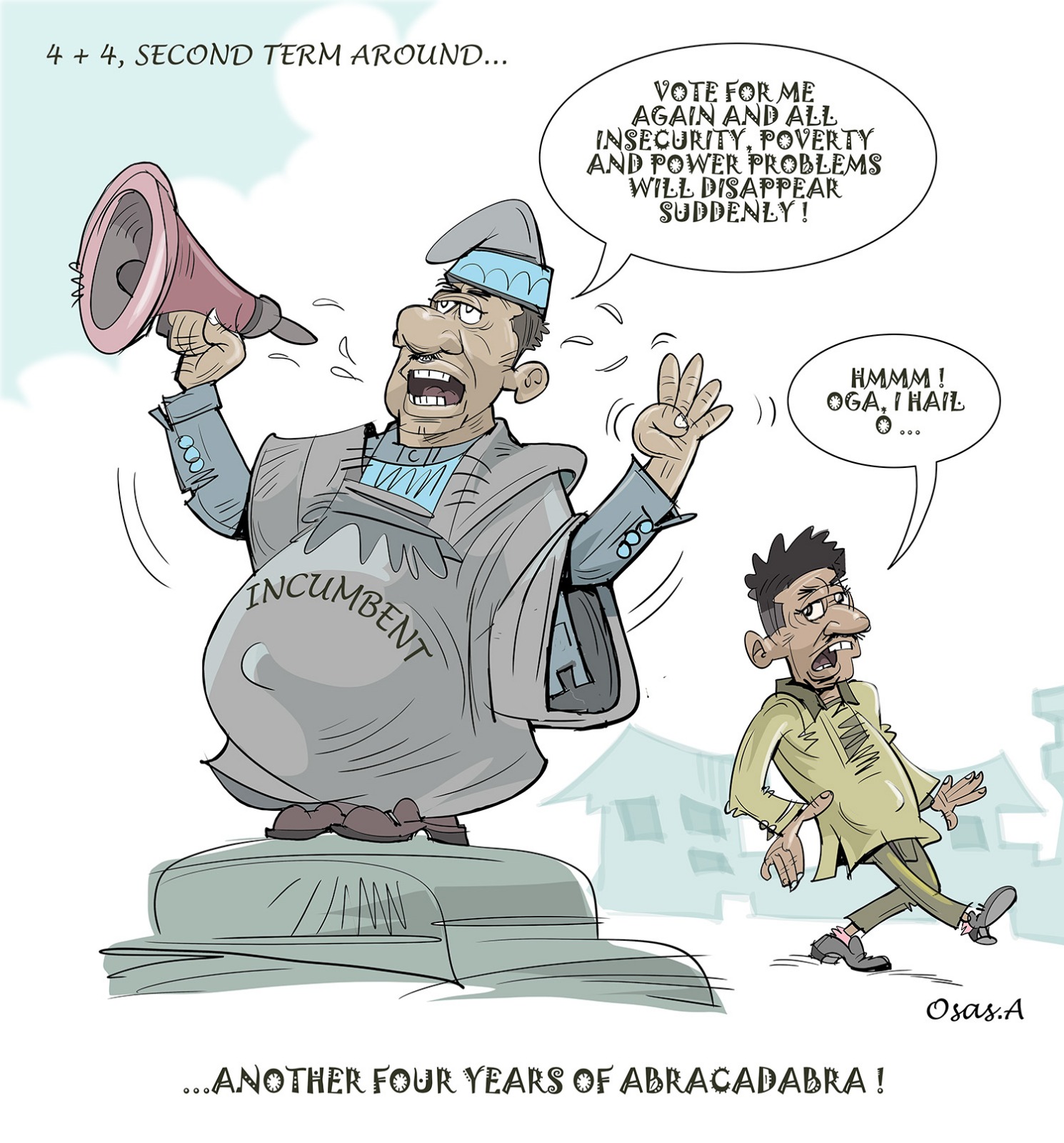

Beyond policy, this shift represents a moral argument about the social contract between citizens and their governments. Terrorism thrives where people lose faith in the state’s capacity to protect them or deliver justice. When governments appear distant, corrupt, or unjust, extremist narratives find fertile ground.

By contrast, reintegration programs that visibly empower victims and hold perpetrators accountable rebuild trust in governance. They demonstrate that peace is not simply the absence of war, but the presence of fairness and inclusion.

As the AU reviews its Continental Counter-Terrorism Framework, first adopted in 2002, the continent has an opportunity to shift its focus from military dominance to community resilience. The lessons from Borno, Diffa, and Kismayo show that African solutions rooted in justice, empathy, and shared recovery rather than imported models can emerge from within.

Although imperfect, Nigeria’s 2:1 initiative embodies a distinctly African ethos which implies that forgiveness must walk hand in hand with fairness, and reconciliation must come with trusted repair. If scaled and refined, it could become a moral compass for Africa’s next phase of security thinking, one that sees the victim not as a passive sufferer but as a partner in rebuilding.

After years of devastation, Africa’s greatest battle is no longer on the battlefield but in the hearts and minds of its people. The continent’s leaders must now pursue a victory measured not by the number of insurgents defeated, but by the trust restored and the justice rebuilt. The true triumph lies not in ending war, but in restoring faith in the promise of peace.

Ujene is a sociologist and criminologist at Miva Open University, Nigeria, and a postdoctoral fellow at the Centre for Education Rights and Transformation, University of Johannesburg, South Africa. He is currently a visiting scholar at the Nordic Africa Institute, Uppsala, Sweden.