Chronic power shortages are shutting down essential services in some rural communities in Ogun State and quietly pushing patients away from government-owned primary health care centres that should be their first point of care. A visit to three PHCs in the state shows how workers now depend on generators, weak solar panels and patient-supported fuel to keep basic services running. IJEOMA NWANOSIKE and MUSA ADEKUNLE report.

The outages, which have persisted for years in many rural facilities, continue to drive residents away from PHCs despite being the closest and most affordable option. These gaps remain even as Nigeria expands solar energy investments nationwide.

According to Orodata Science’s 2024/2025 State of Power in PHCs report, Nigeria added 63.5MWp of new solar capacity in 2024, becoming Africa’s fifth largest installer. Yet allocations to PHCs remain untracked, donor-driven or anecdotal, leaving frontline clinics to operate on fragile, improvised power systems.

Health workers say this disconnect between national energy gains and local realities is now damaging maternal and child health in the communities that rely on them the most.

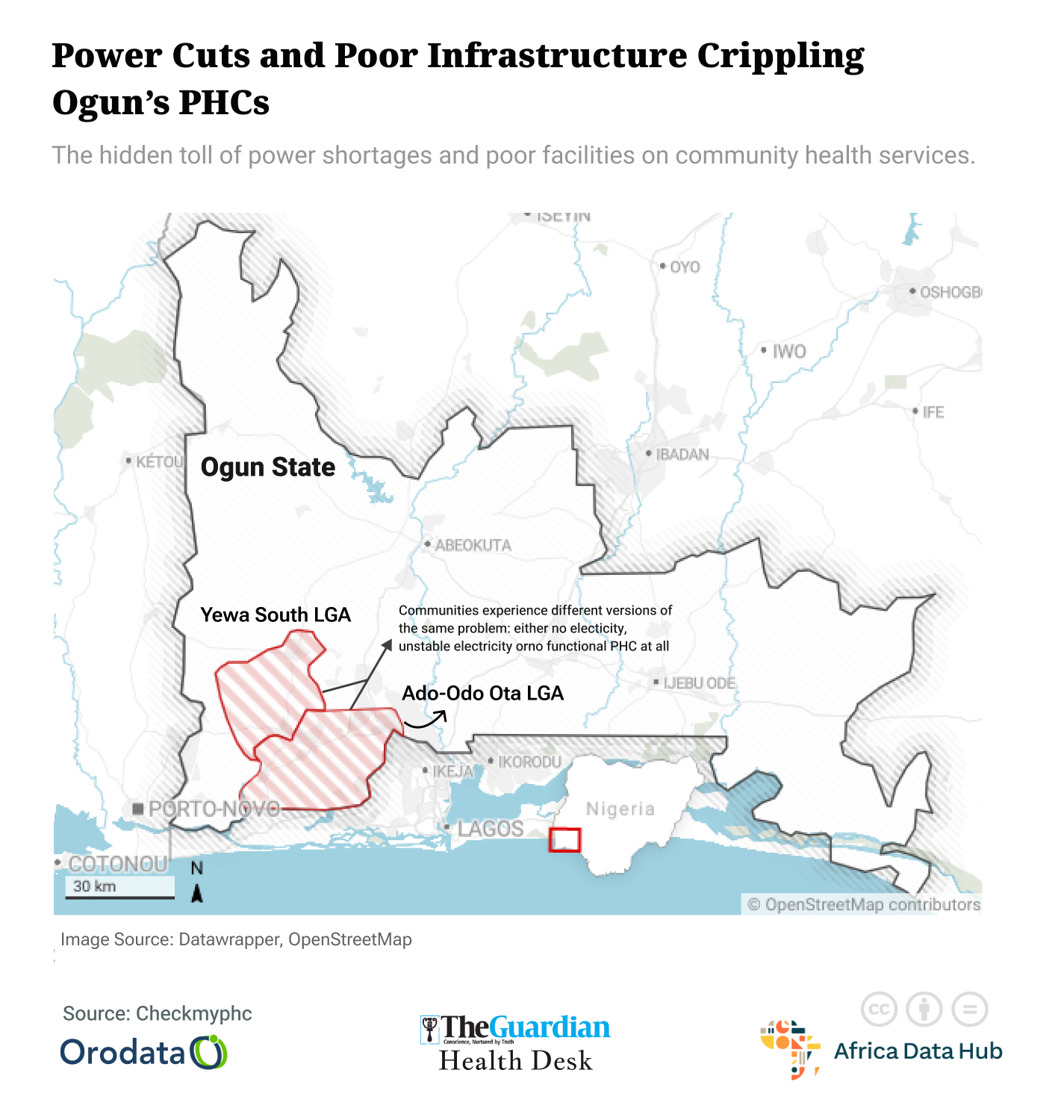

In Yewa South and parts of Ado-Odo/Ota, the consequences are immediate and structural. Deliveries are referred to state hospitals, vaccine storage depends entirely on solar power, and many residents now bypass nearby PHCs altogether.

In communities where promised PHCs were never completed, the situation is even more dire. Residents travel long distances for emergencies in a system meant to bring care closer to their homes. As health workers continue to struggle with unreliable infrastructure, confidence in rural clinics is eroding, deepening concerns about access, affordability and safety.

For many Nigerians, the shout of “Up Nepa” still reflects the country’s long struggle with electricity. Inside primary health centres, however, this same power crisis is quietly weakening the services meant to protect women and children.

During the visit to two PHCs in Yewa South and Ado-Odo Ota, The Guardian found that the Igbogidi, Leslie, and Ijako–Isorosi communities are experiencing different versions of the same problem: either no electricity, unstable electricity, or no functional PHC at all.

At Igbogidi PHC, workers said the facility lost its power supply after a moving lorry dragged down the cable connected to the building.

One health worker said, “A truck passed this road and cut our wire. Since that day, we have been on fuel and Solar. We only use the solar when the sun is strong because it does not carry much.”

The centre’s generator, which sat idle during our visit, is only switched on when strictly necessary.

A staff member added, “We cannot put on the generator every minute. We only use it when we want to pump water or when a patient comes with something urgent.”

Another said, “People do not come to the hospital; now they depend on agbo, they put leaves together and drink.”

At Leslie PHC, the situation was worse. Workers said residents now bypass the clinic for state or federal hospitals because they know the centre cannot cope with the prolonged power outage.

A staff member said, “People prefer to go to the state hospital. They know we do not have light here. It is affecting us because even ordinary fan cannot work.”

He noted that the centre survives on patient-supported fuel payments.

He said, “It is the money patients pay that we use to buy fuel. That is how we survive here. We even generate money for the government.”

He added, “Delivery needs light. Dressing a wound needs light. Even storing vaccines needs light. Without power, everything becomes stressful.”

Residents living around the centres said trust in PHCs is dropping, especially among pregnant women afraid of being left in the dark during labour.

The conditions at Igbogidi and Leslie mirror earlier findings in Ogun State, where health workers rely on fuel, candles or patient contributions to deliver care.

They say restoring trust will require stable electricity and regular supervision to ensure rural facilities are not abandoned.

One of them said, “If government gives us steady light, these places will come back to life. People will return. But until then, they will keep running to big hospitals.”

The situation raises deeper concerns about the future of primary health care delivery in rural Ogun communities and how Nigeria’s energy crisis continues to shape health outcomes.

These local problems reflect national gaps flagged in the country’s energy health system. Budget records show that although states, including Ogun, reported significant health spending, electrification of PHCs remains inconsistent. Ogun State’s 2025 Approved Budget includes ₦33.5 million for PHC utilities and more than ₦27 billion for primary health services, yet rural workers say these allocations have not improved electricity access.

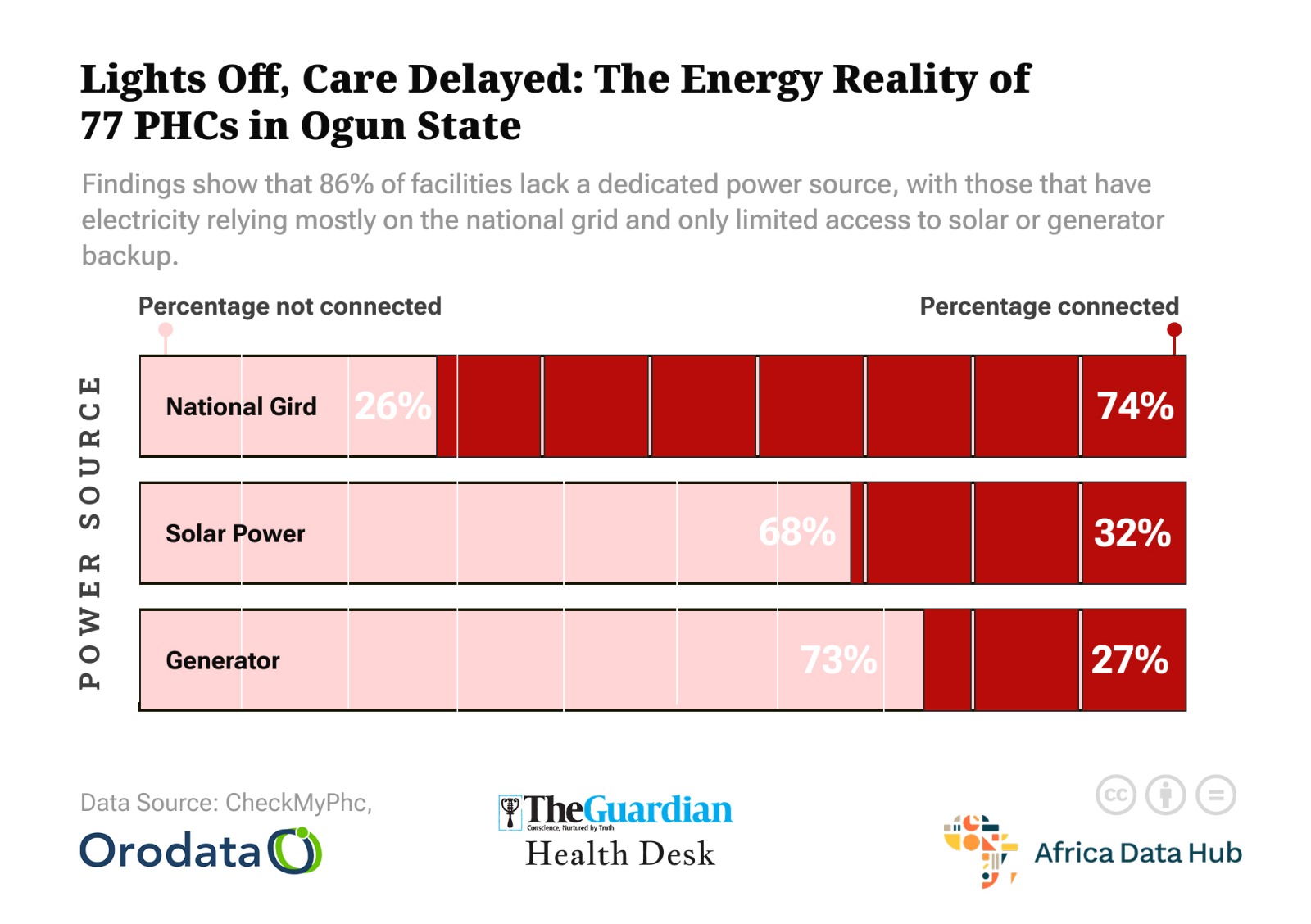

The Orodata review also highlights heavy reliance on scattered solar donations without a coordinated energy health strategy, limited collaboration between ministries, and little performance tracking linking electricity to health outcomes. Without maintenance plans, many solar systems installed in PHCs remain weak or non-functional, leaving antenatal care, labour services and vaccine storage vulnerable to interruptions.

In Ijako–Isorosi, near the Sango axis of Ado-Odo Ota, the challenge is different but equally severe. The community has no functional PHC. Leaders said land for a PHC was donated in 2007, yet nearly two decades later, the building remains uncompleted. Residents contributed money to buy blocks and cement, but construction stalled at the lintel stage.

Village head Chief Muhamadu Jamiu told The Guardian that the absence of a PHC forces residents to travel long distances to Owode or Ewupe for emergencies, delays he said have claimed lives. He said some leaders can afford private care, but most residents cannot.

Former ACDC chairman, Chief Rasheed Adekanbi, who has championed the project for years, recalled multiple deaths that occurred while transporting patients to faraway hospitals. He cited a woman who died after a severe headache because help did not arrive in time.

The community is calling for government intervention to complete and equip the PHC.

These realities unfold against national health indicators that continue to worsen. The 2024 Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey shows that only 46 per cent of births in Nigeria were attended by skilled personnel. Antenatal care coverage dropped from 67 per cent in 2018 to 63 per cent in 2024, taking the country back to 2013 levels.

Child health outcomes also declined. Zero dose children rose from 19 per cent in 2018 to 30 per cent in 2024. Health workers in Ogun say these numbers reflect what they witness daily: families avoiding PHCs because of power failures, incomplete buildings and unreliable services.

Until electricity becomes stable, infrastructure is completed, and public confidence is restored, they fear that Nigeria’s primary health care system will continue to weaken, with consequences that extend far beyond.

This story was produced by the Guardian Newspaper Health Desk, supported by the Africa Data Hub and Orodata Science.