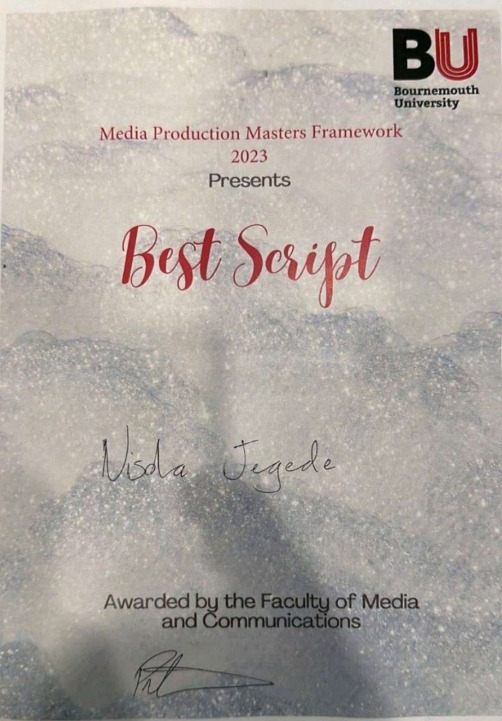

From storytelling and theatrical productions, Nisola Jegede is scripting a distinctive space for herself in the creative world. A Nigerian-born writer whose journey began behind the scenes, Nisola has evolved into a compelling voice for African dramatic narratives. Her training at the EbonyLife Creative Academy and award-winning master’s degree in Scriptwriting from Bournemouth University laid a strong foundation for crafting vibrant, character-driven work that resonates on and off the stage.

In this conversation with our correspondent, we unpack how she balances tradition and innovation, oral history and theatrical delivery to leave audiences moved, questioning, and inspired.

Let’s start from the beginning. What inspired you to start writing for theatre, and how has your journey as a stage storyteller evolved over the years?

Absolutely. I think I’ve always been developing stories—even if I wasn’t writing them down. As a child, I would watch movies and, if I didn’t like them, I’d immediately start reimagining how they could’ve been better. That instinct to reshape narrative has always been with me.

Growing up, my family lived beside a woman who sold books, and she was gracious enough to let me borrow them—as long as I returned them in pristine condition. I’d read and then start redeveloping the stories into something more reflective of what I felt or imagined.

But what truly drew me to theatre was my experience studying English and Literary Studies at Federal University Oye-Ekiti. I took some courses in the Theatre and Media Art Department, and that opened a whole new world for me. I made so many friends there who would invite me to their productions. And with each performance, I fell deeply in love with each production.

There’s something magical and enchanting about watching actors and actresses enact their roles and breathe life into lines. That experience helped me realize how rich and resonant our African stories are, and more importantly, that I wanted to be part of telling them.

I went on to connect with Mr. Taiwo Oloyede, and we started working together, specifically on crafting dialogue for theatre productions. We’ve been collaborating since 2020, just before the lockdown, and that has been a significant part of my growth as a storyteller in theatrical spaces.

The plays you have worked on often explore layered identities and lived realities. How does your Nigerian background influence the way you approach character development, dialogue, and staging in your theatrical work?

While I only worked on the dialogues of these plays, I would say my Nigerian background shapes every part of my creative process—from story development to rewriting. It influences how I approach characters, voice, and setting. In Nigerian storytelling, what a character says is rarely the whole story. There’s often a gesture, a silence, or a proverb tucked beneath the surface of the dialogue. That layered communication is central to how I build my characters. I try to reflect the richness and nuance of how we speak, implying deeper meaning without always saying it outright.

As a woman, have you faced particular challenges related to gender, either in the stories you tell or the spaces you navigate professionally?

Truthfully, I’ve faced only minimal gender-related conflict in the writing space myself. But the same can’t be said for my female characters. They’ve carried the weight of far more, especially the women in my published short stories. I often reflect on how the world tends to view Black women through a narrow lens: strong, angry, combative. I don’t want my stories to be the same way. But that portrayal doesn’t represent most African women I know. We’re just like women anywhere else—complex, tender, bold when needed—but the emphasis placed on intensity often feeds into the stereotype.

The media tends to reinforce this image, and I’m conscious of it when writing. I don’t want my stories to simply echo that portrayal. At the same time, it’s tricky. If my female characters are soft, people might say they lack spirit. If they show strength in an African way—through silence, endurance, wit, or controlled fire—it risks being misread as anger. So it’s a constant balancing act: telling the truth without feeding the trope. I suppose my challenge is writing characters who burn, but burn on their own terms.

Now, based on your creative journey as a whole, how do you navigate and explore the complexities of Nigerian identity, diaspora identity, and perhaps even a broader global identity, in your fiction?

For me, I don’t see identities as fixed categories. I feel characters overlap, conflict, and reshape each other depending on where the story is being told and who is reading it. In my work, especially in some of the stories I contributed to, I often explore characters who exist between things, between tradition and self-identity, between inherited beliefs and personal truth, between where they are from and where they are now. That in-between space is where I feel most creatively alive, because it mirrors what it means to live across cultures: to constantly translate yourself, even to yourself.

Do you find yourself writing back to home, or writing forward into new cultural terrains in your stories?

I always find myself writing home, but this is for a reason that cannot really be explained. Like, I write back home to uncover, question, and sometimes challenge the things I grew up around but don’t understand, and I am trying to. So, my stories often return to home as a concept, a conflict, or a memory that I would like to fully understand. This may be among the things that make my characters very human. They look for those answers and don’t get everything all the time. However, they always find fulfilment in the journey of the search for those answers.

As a woman navigating both the literary and theatrical worlds, what barriers or breakthroughs have defined your creative journey so far?

Hmmm. One of the key challenges I have faced is balancing vulnerability with authority. In both literary and theatrical spaces, women are often expected to write emotionally but not be “too assertive” or to lead quietly. Another defining part of the journey has been collaboration. Unlike literary writing, which is often solitary, theatre is deeply collective. Working on Folklore and the Gyration of the Oppressed taught me how to let go of control, to allow the writer and director, the actors, and designers to reinterpret my words without losing their essence. The real breakthrough came when I started treating both worlds not as separate lanes but as parts of the same creative language. Whether I am writing a short story or shaping dialogue for the stage, the goal is the same: to tell stories that feel honest, layered, and rooted. Once I understood that, everything became more fluid and more fulfilling.

What aspects of female experience and empowerment in Nigeria do you aim to highlight through your stage characters, and what messages do you hope to convey about gender roles and societal expectations in your works?

I am drawn to what makes most Nigerian women, them. Most of the women around me are people who have shown small acts of resistance, survival, and redefinition that happen in everyday life. You know, the actions that are quieter, often overlooked aspects of the female experience. These are the women I am interested in. The woman who stays but changes the rules, the girl who questions tradition without fully rejecting it, the matriarch who carries both power and silence. The message is not always about breaking free. Sometimes, it can be about shifting shapes. About adapting, questioning, and rewriting roles from within. Because empowerment doesn’t always look like defiance, it can look like a woman choosing to name herself differently, even in the same room.

I am drawn to what makes most Nigerian women, them. Most of the women around me are people who have shown small acts of resistance, survival, and redefinition that happen in everyday life. You know, the actions that are quieter, often overlooked aspects of the female experience. These are the women I am interested in. The woman who stays but changes the rules, the girl who questions tradition without fully rejecting it, the matriarch who carries both power and silence. The message is not always about breaking free. Sometimes, it can be about shifting shapes. About adapting, questioning, and rewriting roles from within. Because empowerment doesn’t always look like defiance, it can look like a woman choosing to name herself differently, even in the same room.

You mentioned you have written a short African fantasy, and you are hoping to focus on that genre. How did you bridge the game between African mythology and fantasy with social critique by the use of imagination to address issues around dependence, agency, and belief systems in your story?

For me, imagination is a tool that should be used to sharpen the truth. With it, I ask myself: What happens when tradition becomes a trap? What does agency look like when the divine has already spoken? Fantasy gave me the tools to explore those questions without having to flatten the complexity of belief, obedience, and selfhood. In Unwilled, I approached African fantasy as a space of confrontation. I approached it as a space where myth and magic reveal the quiet conflicts people carry. The story is rooted in spiritual inheritance, but at its core, it is about choice or the illusion of it. I was able to use the elements of African mythology to frame a world where belief systems can be both external forces and internal burdens.

Finally, what continues to drive you to write, and what kinds of stories do you still hope to tell about identity, gender, and place in the years to come?

I am into several forms of writing. Literature and theatre. However, what drives me to write remains the same and that is the need to explore identity as a negotiation. I believe it shouldn’t be a fixed label as long as nothing illegal has been committed. I want to write about genders in ways that should. Also, I want to write about the silent conflicts or the emotional weight women carry without using their words. I write to explore those things, even if they can’t be resolved sometimes.