[dailymotion code=”x893u0w” autoplay=”yes”]

The performance of the country’s export sector has been on a downward slope. And it took what appeared to be a steep dive into the basement last year, exposing the sordid underbelly of the country’s export promotion and import substitution programmes.

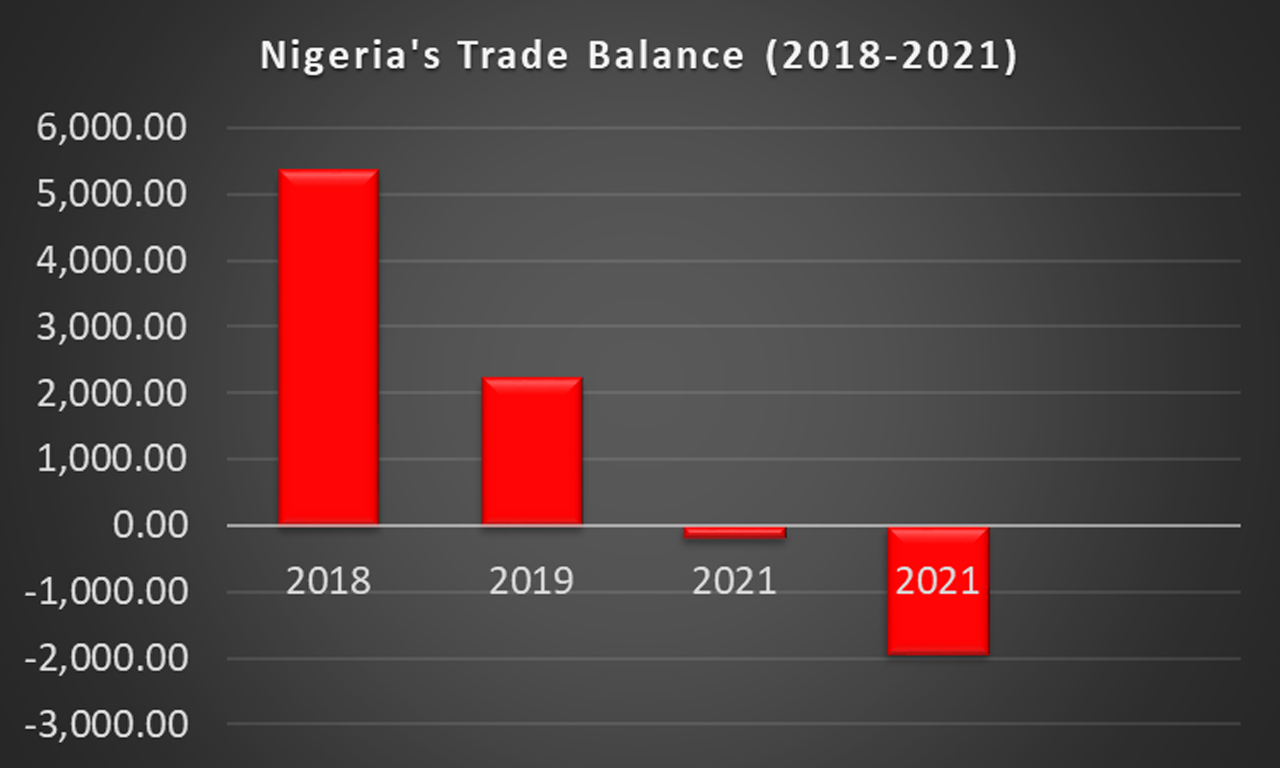

Nigeria’s trade balance had remained relatively healthy until sometime in 2019 when it started recording deficits. This got bad last year when it jumped 986 per cent, growing from N178 billion to an all-time high of N1.94 trillion. The shortfall is about 10 per cent of the total value of exports in the same year.

The amount is also about 2.7 per cent of the country’s real gross domestic product (GDP), which was estimated at N73.4 trillion last year.

If the huge trade deficit is worrisome, the data trend and pattern in recent years are, perhaps, frightening. In 2018, the country recorded a trade balance of N5.37 trillion; the figure slipped to N2.23 trillion in 2019 but that was still considered a healthy position.

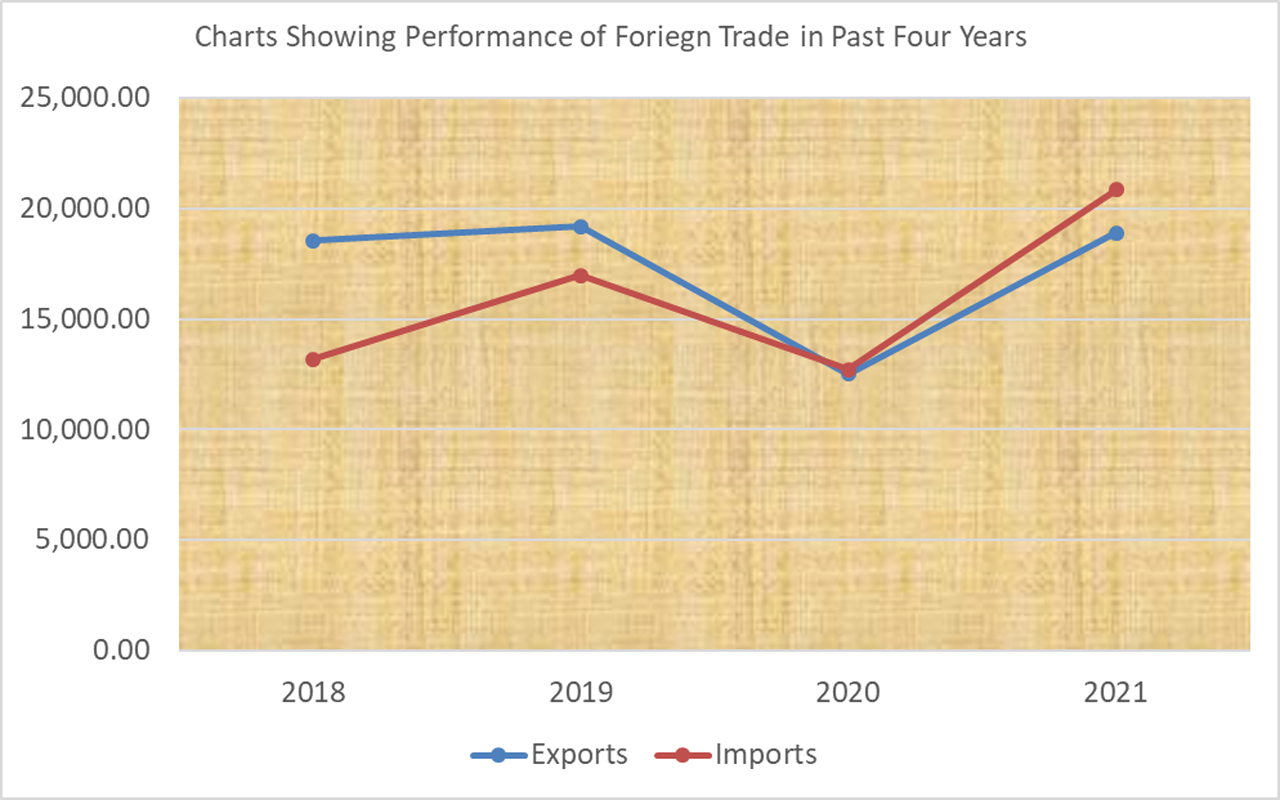

The following year, trade volume slumped globally as the economy grappled with the restriction of movement of persons. Nigeria’s exports suffered a haircut of 35 per cent, climbing down from N19.19 trillion to N12.52 trillion. Imports also fell substantially but not just enough to cancel out completely the wide hole created by the falling crude prices in the export figures.

At the close of the year, Nigeria’s hitherto positive balance of trade went into the negative region, leaving a deficit of N178.26 billion only for the figure to balloon to nearly N2 trillion last year.

Trade, of course, is a flow variable. As expected of every sector, it should expand continuously to match the speed of economic and population growth. Thus, the value of trade between Nigeria and other countries grew by 25 per cent between 2018 and 2021, during which the figures moved from N31.7 trillion to N39.25 trillion. However, the growth was driven by the export component.

In 2018, Nigeria’s yearly exports were valued at N18.53 trillion and only gained marginally to reach N18.91 trillion last year, implying that the country’s exports grew by only two per cent. In dollar terms, what the country earned in the form of the export injection last year was less than the value of earning four years earlier. This is because the value of naira had depreciated by, at least, 10 per cent at the official market, within the period.

The position of both export and import on the trade chart in 2018 as against last year is also revealing of a scary future in the near- to medium-term. In 2018, the share of exports in the total foreign trade was 58 per cent. But as of last year, imports had grown by about 58 per cent reversing the ratio to 52:48 in favour of imports.

The value of the country’s imports has been growing at a speed not seen in the history of the country while exports revolve around a constant figure. In economic theory, imports are considered as leakages while exports are injections. The latter increases local capacity utilisation, including jobs, while the former fritters away or creates jobs for other economies. This relationship, except it changes soon, suggests the labour market outlook is very scary.

Beneath the broad categories, disaggregated analysis of the trade data also gives an insight into the low capacity of the local economy to create jobs and build inclusive growth.

In the four years reviewed, crude and oil products accounted for an average of 89.4 per cent of the total goods exported, leaving industries and agriculture where the bulk of the jobs are created with about 10 per cent. Despite the renewed campaign for non-oil exports, oil still controlled 88.7 per cent of the export basket last year.

Of the meagre 10 per cent controlled by other sectors, raw material accounted for 2.68 per cent. The dominance of the country’s export mix by raw materials and commodities, whose prices and volumes are determined by external factors, is compounded by Nigerians’ growing appetite for foreign manufactured goods.

Last year, for instance, manufactured goods accounted for 49.82 per cent of the value of imports. This figure excludes oil products, which took 30.96 per cent. The two items – which are essentially by-products of raw materials sourced from developing countries, including Nigeria – took away N16.84 trillion in foreign earnings from the economy last year. The amount equates 81 per cent of all the export leakages. In sharp contrast, less than three of the export earnings of last year came from manufactured goods.

This has a huge consequence for the foreign exchange (FX) market and employment creation. The country, with enormous unemployment and FX challenges, is by implication ‘outsourcing’ critical segments of the economy that create jobs (secondary production) to other economies. In simple terms, Nigeria has continued to export jobs owing to its inability to domesticate heavy factor industries.

Some experts are genuinely worried that these paradoxes are an invitation to major socio-economic crises whose full manifestation the country may not cope with.

The leadership of the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) shared this concern recently when it was compelled to respond to the shrinking non-oil commodity processing through the RT200 FX Programme, a policy thrust that targets yearly repatriation of $200 billion from non-oil exports in the next three to five years.

Nigeria produces about 770,000 metric tonnes of sesame, cashew and cocoa in 2019. Of the number, about 12,000 metric tonnes are consumed locally while 758,000 metric tonnes are exported. The unfortunate thing though is that of the 758,000 metric tonnes that were exported, only 16.8 per cent was processed. The rest was exported as raw, thereby denying Nigerian farmers a significant share in the value chain.

Also, the global chocolate industry was estimated at $130 billion in 2019. Sadly, Cote D’Ivoire, Ghana and Nigeria, which controls about 72 per cent of the cocoa exports did not receive more than five per cent of the windfall or $6.3 billion. According to the CBN Governor, Godwin Emefiele, the three West African countries in that order generated about $3.6 billion, $1.9 billion and $804 million from the industry in the reference year.

“In contrast to West African countries, Belgium accounted for 11 per cent of global chocolate exports in 2019, at a value of $3.16 billion. Similarly, Germany’s chocolate exports were worth $5.14 billion in the same year. These numbers are the same for other commodities as well,” Emefiele said.

The poor performance of the country’s exports, economists have argued, has a strong correlation with the labour market. Last year, the country’s unemployment rate relapsed to what many analysts described as a crisis level – 33.3 per cent — while youth unemployment exceeded 40 per cent.

Unemployment and FX crisis-induced inflation are among the endless social challenges caused by low industrialisation. Dr. Austen Nwanze, who teaches entrepreneurship and business management at the Lagos Business School, added that insecurity is a major effect of the challenge. Unfortunately, insecurity has graduated to a cause and effect in the dysfunctional system that has become part of the country’s economic culture.

As the majority of young people cannot get jobs, they take up arms against society, kidnapping for ransoms while engaging in other violent crimes. These in turn raise economic risks, which further narrow the business space and the capacity of the economy to create or retain jobs. The vicious circle could continue indefinitely. Breaking this ring can potentially increase the prospect of building a prosperous future, some stakeholders have advised.