The year was unthinkable. There was a pandemic that stung the global economy and, for several months, refused to let go.

After the mid-year, there was a momentary relief when it appeared that the curves were, indeed, flattening. But the economy could get a brief lift when the second wave, and all the unpleasant news about resurgent impacts on the economy, struck once more.

The challenging 2020 closed with so much worry about the second wave (perhaps, this is a generic name for a returning COVID-19 as the globe has experienced a second wave more than twice). There were also breakthroughs in vaccinations.

Sadly, a few countries have also reported new strains of the virus just as infectious disease experts believe there is yet an end to its mutation. These have raised fresh concerns about the medical challenge that has dealt a deadly blow to the economy.

But it is not much about COVID-19 in the case of Nigeria. The outbreak has only exposed the underbelly of a weak economy as experts believe that Nigeria had been battling with self-inflicted systemic challenges.

For instance, Head of Macroeconomic Research, EFG Hermes, Mohamed Abu Basha, says “the economy has yet to adjust to this drop in oil prices” that triggered the 2016 recession, which lasted for five quarters.

The economy has, in the past decades, spiraled downwards over sore points ranging from fiscal indiscipline, executive recklessness, official graft, policy summersault, currency crisis, unemployment, reliance on importation, narrow economic base, poor capacity utilisation to inadequate infrastructure. The government, according to Bala Zakka, a financial analyst, has only paid lip service to “fixing these systemic challenges”.

From the days of military dictatorship and even after 1999, when the current democratic experience birthed, it has been a boom-and-bust cycle. When oil prices rally, as they do occasionally, the economy gets a relief, albeit temporary. During the oil crisis, it drifts, gets battered, and bleeds. The cycle has continued and has become the economic norm.

Efforts at addressing the unfortunate challenges by successive administrations have, at best, been knee-jerk, which Dr. Chiwuike Uba, a development economist, and consultant to the World Bank, says is incapable of addressing deep-seated “systemic economic challenges”.

As COVID-19 ran amok last year, the economic palliatives of past years, in the form of policies and interventions, were washed off, leaving the economy naked. This manifested in weak revenue earnings, soaring public debts, deteriorating infrastructure, weakening naira, escalating inflation, and frightening unemployment

Needless to say that COVID-19 has been friendlier with Nigeria than with many other parts of the world. For instance, one in every 2,258 Nigerians has been infected with the nebulous virus as against a global average infection ratio of 1:93. Also, Nigeria’s fatality rate is 1.5 per cent compared to a global average of 2.2 per cent.

But Nigeria’s negative economic response is near disaster, experts say. In the second quarter of the year, the country began a sad return to a recession about three years after it exited one. The gross domestic product (GDP) lost 6.1 per cent the same period the economy of China, where COVID-19 started in 2019, grew by 3.2 per cent, 70 basis points above experts’ predictions.

In Q3, the contraction was mild, at 3.62 per cent, raising the hope that the economy could exit recession early this year. The governor of the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN), Godwin Emefiele, did say he was “cautiously optimistic” the economy would return to positive growth in Q4 2020.

Many other economists, including Dr. Biodun Adedipe, a leading financial expert, agree with Emefiele that the economy has begun the journey to recovery.

Adeola Adenikinju, a professor at the University of Ibadan, who sits at the Monetary Policy Committee with Emefiele, points out the recuperating international oil market as a case for Nigeria’s positive growth.

Indeed, between Q2 when Nigeria slumped by over six per cent and December 31, 2020, oil prices had witnessed a price rally of over 100 per cent. As the curtain fell on the year, Prices hit an average of $50, still far below the pre-COVID-19 era but strong enough to stir hope for economies that depend on hydrocarbons.

Of course, this is the major challenge with Nigeria’s economy – an economy that is constrained and driven by the oil market!

Even in the face of a resurging oil market, the most optimistic economists admit that there are still sufficient headwinds to cause reasonable worries. Prof. Adenikinju, who is also the Director of the Centre for Petroleum, Energy Economics and Law of the University of Ibadan, says the international market is “still very uncertain”.

The crisis in the international oil market has caused a major stir in Nigeria’s foreign exchange market – an irritation the country had to live by in the whole of the year. As foreign exchange earnings nosedived, the apex became increasingly incapacitated in its efforts to defend the tumbling naira across FX windows while the external reserve kept depleting, dropping to less than $35 billion by mid-December

Rising exchange rate, which has become like a falling knife on Nigerians, was particularly troubling last year. At the turn of the year, the naira traded at a CBN official rate of N305/$ but it closed the year at 379/$, losing 24 per cent of its value against the dollar in just 12 months.

But the trouble was much deeper in the parallel market, where the local currency lost about 30 per cent. It could have been higher but for the recent adjustment in remittance management policies, which saw the spiraling dollar retreating from about N500/$ to N470/$ at the close of the year.

The situation was worse for other major currencies. Against the Euro, the naira lost about 40 per cent of its value, trading at N570/€ on December 31 compared with N409/€ it opened the year with at the parallel market. The naira also traded for N455/£ while Nigeria welcomed 2020. But the pound would later move up the ladder steadily to hit N628//£ on the last day of the year, translating to a 38 per cent gain in favour of the former colonialist currency.

Against Asian and African currencies, the naira kept tumbling. And it signed off the year with a reasonable haircut when it fell further to N410.25/$ at the Nigerian Autonomous Foreign Exchange (NAFEX) window on December 31.

A tumbling naira also meant an unbearable cost of living that has continued into the new year. For Dr. Ayo Teriba, an economist, Nigerians will need to live with the excruciating pains of the high cost of living until the country grows its non-oil earning to a reasonable level.

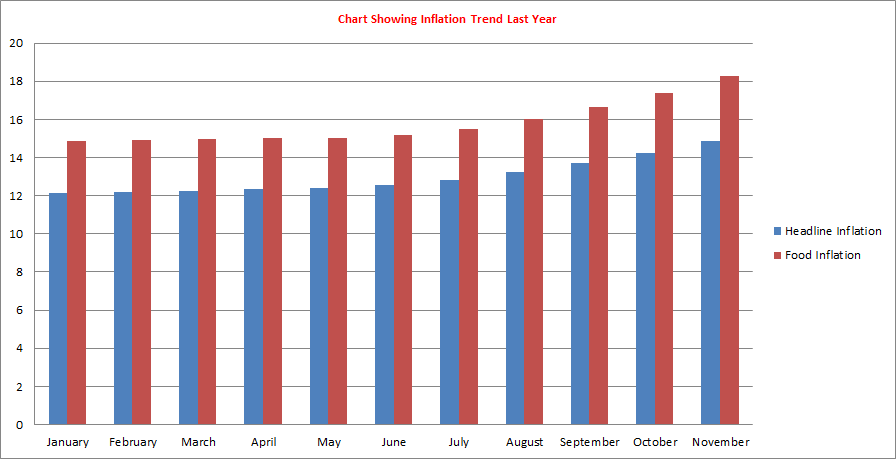

In the figure, the year started with headline inflation of 12.13 per cent and remained on an upward trend month-on-month through the year to hit 14.89 as of November, gaining 2.76 parentage points in nine months. The rise was steeper than the 0.48 percentage point gained in the corresponding period last year.

Also last year, the headline inflation maintained an unbroken month-on-month positive pattern. The closest was in 2015 but the trend flattened in November 2013 when the inflation retreated from 9.4 per cent to 9.3 per cent.

Food inflation became even more worrisome in the Consumer Price Index (CPI). At the turn of the year, it was 14.85, almost 100 basis points higher than the composite inflation. A month to the close of the year described as extraordinary, the difference between the two parameters was 250 basis points plus, as food inflation stood at a three-year high of 18.3 per cent.

In 2020, Nigeria overstretched its fiscal position up to what many people consider as a fiscal cliff. The country entered the year with a total debt profile of N27.4 trillion. As of September, the debt stock had risen to 32.2 trillion, growing by approximately 4.8 trillion in three quarters as against N3 trillion accumulated in the whole of 2019.

The burden of servicing the debt is already eating the government’s cash flow. In Q1 2020, for instance, the Federal Government spent 99 per cent of its total earnings on debt service, which is disastrously high going by World Bank’s recommendation.

In 2019, there were reliable and acceptable figures on the country’s labour market but last year, the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) gave the country some data to worry about. The unemployment rate, in Q2 2020, soared from 23.1 per cent it was the previous time a survey was conducted (Q3 2018) to 27.1 per cent. The underemployment rate was even higher at 28.6 per cent, up from 20.1 per cent two years earlier.

In summary, 55.7 per cent of those in the labour market estimated at 80,291,894 were either jobless or not fully engaged. By implication, 44.7 million individuals who were willing and able to work were either partially redundant or unemployed.

But the devil was evil more in the analysis of the employment figures versus the number of persons in the economically active or working-age population (15 – 64 years) which was estimated at 116,871,186. This is over 45 per cent higher than the size of the labour market. There could be different reasons why such a high number of people do not participate in the labour market. A number of them could be in school or preoccupied with other responsibilities (including harmful ones) that could also be disturbing. In the Nigeria case, exhaustion and despair could also be reasons some people do not see themselves as job applicants.

Notwithstanding the exhilarating immediate past, Nigerian firms, in the December 2020 Business Expectations Survey Report, say the country can look forward to a positive 2021 as the year begins in earnest.