“Putin thinks he is strong because Russia is the second-largest oil exporter in the world. But he is weak because he has put himself in your hands and you are angry because he is terrorising Ukrainian civilians and threatening the world,” a traumatised Oleg Ustenko, an adviser to the Ukrainian President on economic issues, said in an article seeking global blockage of Russian oil.

“Putin thinks he is strong because Russia is the second-largest oil exporter in the world. But he is weak because he has put himself in your hands and you are angry because he is terrorising Ukrainian civilians and threatening the world,” a traumatised Oleg Ustenko, an adviser to the Ukrainian President on economic issues, said in an article seeking global blockage of Russian oil.

Reference to the article is not much about the Russian onslaught in Ukraine, but the importance crude plays in global politics, especially in wartime. Indeed, President Putin’s strongest convincing point that he can get away with what his critics have described as impunity is that “Russia is the second-largest oil exporter in the world” and that Europe, especially, cannot as much contemplate a world without Russia’s daily five-million-barrel supply.

An average of 35 per cent of oil and gas consumed by the European Union (EU) is supplied by Russia. If the region can do without ‘blood oil’ (as Russia’s crude has been brutally labelled since the war outbreak, Putin knows he could kill more Europeans if the EU dares him by cutting off the gas supply. And he has threatened to, so, the world should block oil vessels from Russia.

Already, this has caused a dilemma, with some members of the EU rejecting the plan to ban oil supply from aggressive Russia.

So, the hesitation of the West, particularly Europe, is understandable and reinforces the notion that a barrel of crude is more valuable than blood in wartime. This paradox, with the invasion, could not have come at a worse time.

According to the February U.S. consumer price index (CPI), gas price has increased by 38 per cent year-on-year (YoY), accounting for a third of the index monthly rise. Europe has had to deal with the worst apprehension over surging gas prices and disruption from its major supply source will be a devastating addition.

Like other regions, European governments are becoming increasingly concerned about rising inflation, which has transitioned beyond a mere passing phenomenon. From the US to Europe, economies are posting inflation data not seen in the past three to four decades.

Last week, the President of European Central Bank (ECB), warned that the attack on Ukraine, which she described as a “watershed moment” could escalate the situation, cautioning policy makers against turning their backs against rising prices.

There are sufficient analyses on how supply shock could set new price floors for some commodities and raise the concern over steep inflation. As at weekend, the global price of wheat, with a quarter of global supply sourced from Russia and Ukraine, was 34.3 per cent up in the past month. As bad as the situation is, the global economy may yet be enjoying a lag waiting for the full impacts of the war on oil prices.

Since World War II, energy cost has been treated as a distinct variable in production modelling as the commodity could have an equal or more serious impact on the overall cost as other factor inputs – labour and capital. Households are, once again, at a critical point as rising energy cost threatens major disruptions in prices, and experts are wondering if the western governments are prepared to deal with the upheavals.

Last week, Brent oil futures traded for as high as $139.13, the highest in 14 years. The market has printed green candlesticks since the war outbreak, with some energy economists already contemplating the possibility of $200 per barrel crude. As typical of a bull run, market reversal appears increasingly remote with each spike. Saudi Arabia has become even more relevant as the US considers it the only producer with the leverage power to crash or, at least, stabilise the prices to keep the cost of production relatively stable.

Like others, the Saudi de facto ruler, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, may have seen the bull as an opportunity to make up for the shortfall at the height of COVID-19 lockdown when crude prices could barely cover the cost of production so he played a hide-and-seek game with the US. The debate over energy transition has been reinforced but it is also obvious the switch will not happen faster than it took humanity to ditch a horse for the automobile. Infrastructure was built just as new infrastructure will be built to transform transportation, which consumes about 25 per cent of global energy.

There is also a question on why the world panics over hydrocarbon shortage. If it were becoming useless as a pro-alternative energy claim, why worry over the shock in its supply? Perhaps, the oil-producing countries will still celebrate one or two more bull runs before the final rug pull by energy transition enthusiasts.

Sadly, Nigeria may just be as worried about the current rising oil prices as the United States or any other high-volume consumers like China or Japan. The rising prices of crude mean more spending on petroleum imports and provision for subsidy. This will widen the fiscal deficit in the 2022 budget, which was initially estimated at N6.4 trillion.

When oil prices buckled under the weight of COVID-19, the situation had a semblance of a falling knife on the economy as the pittances earned was just not enough for anything. With huge debt overhang, rising infrastructure needs and other contingencies, the government could barely pay salaries. But with prices of crude almost doubling the budget benchmark, the worry has only shifted elsewhere – rising premium motor spirit (PMS) subsidy burden has become a pain point.

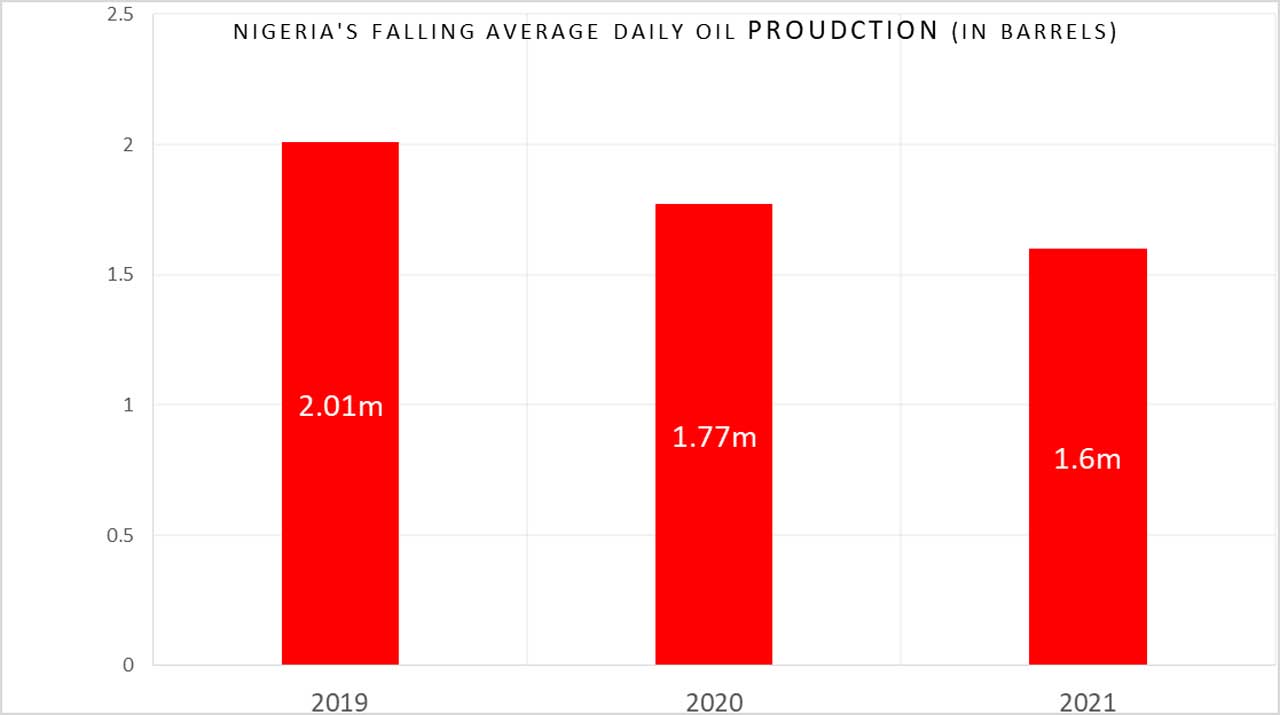

Whether the petrodollar economy can be sustained by the reserve is contentious but what is clear is that the country has not demonstrated that it can sufficiently optimise its production. The figures are telling of the falling performance, and the recent three-year trend is most evident of the sloppy pattern.

In 2019, the average daily production stood at two 2.01million barrels. The figure nosedived to 1.77 million in 2020, which could be excused based on the global lockdown. But the recovery witnessed across sectors last year could not lift the production profile. Rather, output dipped to a record low of 1.6 million barrels per day.

But that is not all. The southward movement in crude production has been most consistent in the past three years. Last year only seemed to have consolidated on the slide on a quarter-by-quarter basis – in the first quarter, the daily production averaged 1.72 million barrels, and shrank to 1.61 million in the second quarter. In the third and fourth quarter, the production level dropped further to 1.57 million and 1.5 million respectively.

In absolute terms, the real output of the sector was N5.2 trillion last year as against 5.7 trillion achieved in 2020 – a year many analysts would jokingly describe as non-existent. The sector bucked the trend last year, sliding by 8.3 per cent amid 3.4 per cent growth recorded by the economy. In 2020, understandably, it slumped by 8.89 per cent. The declining crude production is often attributed to theft, another abnormality nurtured by the country’s peculiarity. The oil companies report losses to theft regularly but, as usual, no concrete actions have been taken to address it.

In response, the international oil companies (IOCs), who have provided the finance, technical capacity and expertise relied on historically to turn the mineral deposit into cash have been divesting. Two weeks ago, Seplat Energy Plc, a leading Nigerian company, said its plans to acquire the entire share capital of Mobil Producing Nigeria Unlimited (MPNU) from Exxon Mobil Corporation Delaware (USA Incorporated) had reached an advanced stage and was awaiting regulatory approval. Shell Petroleum Development Company of Nigeria has been scaling down its investments and could close out its interest in the country in a matter of time.

There is nothing in the book yet to doubt the capacity of local companies to take over from the foreign companies; that may be sufficiently tested sooner than expected. But that is not as important as knowing how the country intends to make the most use of the commodity. Supposing the local firms rise to the occasion, their exploit may not change anytime, just has the IOCs have not in the past decades if the country continues to sell oil, in its crudest form, only to have the foreign earning swallowed by PMS importation cost, which is a rising function of crude prices at the international market.

The foreign exchange market has continued to face enormous pressure from rising import liabilities, with refined products contributing a large portion to the import bills. The most recent foreign trade data available (third quarter, 2021), for instance, motor spirit alone contributed as much as 12.9 per cent to the country’s total imported goods. Petroleum by-products, in general terms, consumed N1.36 trillion or 16.6 per cent of the importation. The figure was less than N1 trillion the preceding quarter. Then, petroleum products shared a total of 15.3 per cent of the total imports. And that has been the trend in recent times – each year, the country spends additional foreign exchange on imported petroleum products while the crude production takes a haircut.

Trade in crude and its by-products essentially symbolises Nigeria’s foreign trade direction. The country exports extractive commodities at compromised prices fixed by the international market and buys them back at exorbitant prices dictated by foreign manufacturers soon after they have been processed. A trade expert and professor of economics, Ken Ife, said the unprofitable practice is a major threat to the country’s trade relations even within the African region.

“Except you add value, you can’t optimise the value of the commodities. Other West African countries come to buy up Nigeria’s agricultural produce, add value (process and package) and re-export to Nigeria to sell at higher prices. We must invest in agriculture, produce value chain and processing to solve this challenge,” Ife said.

Ife’s advice is very relevant to the current stage of agricultural development. The country exports cocoa at give-away prices and imports chocolate at a cut-throat cost. Perhaps, the counsel is relevant to crude oil, not as a matter of need but survival. The level of spending on petrol products and the dimension PMS subsidy has assumed, the economy may have been on life support. And experts have warned that nothing short of inward-looking actions for energy consumption may save the situation.