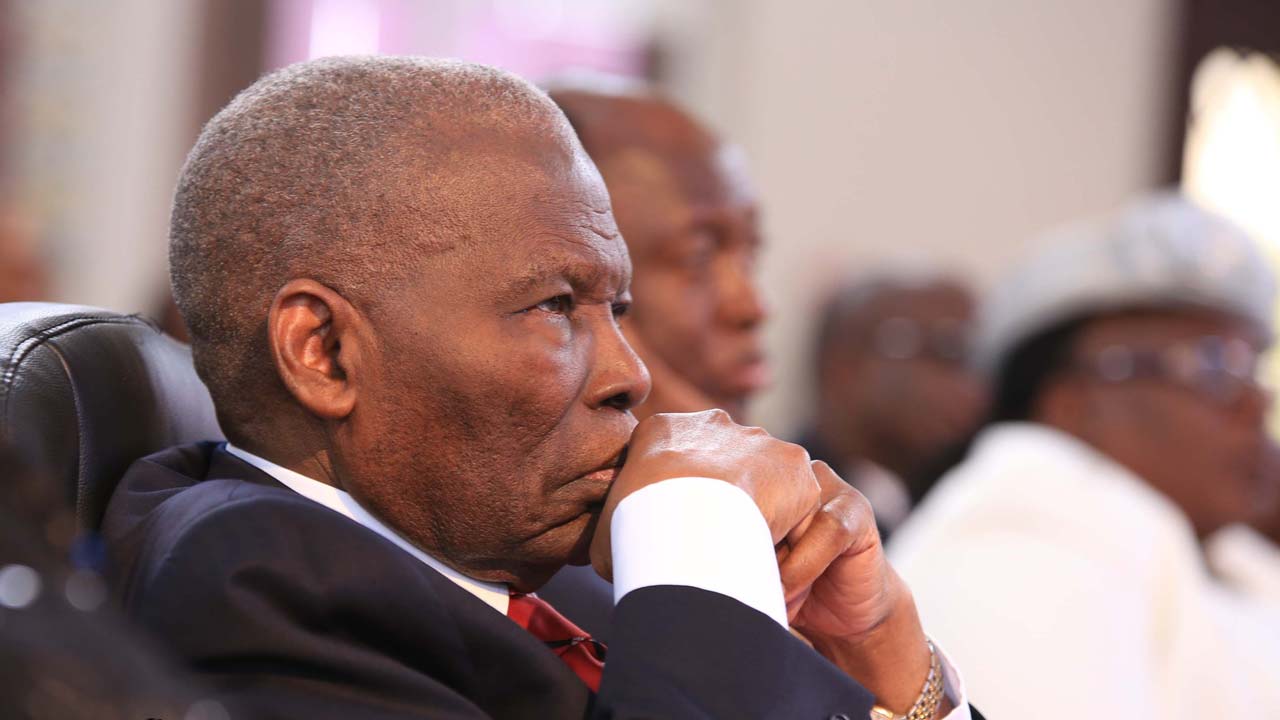

On Sunday, July 13, 2025, Paul Barthélemy Biya’a bi Mvondo, President of Cameroon, widely known as Paul Biya, added another feather to a brand of ignoble achievements. Already the second-longest-ruling president in Africa (after Equatorial Guinea’s Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo), the current oldest head of state in the world, and the longest consecutively serving current non-royal national leader in the world, Biya took to the X social media platform, announcing, “I am a candidate for the October 12, 2025 presidential election. Rest assured that my determination to serve you is commensurate with the serious challenges facing us. Together, there are no challenges we cannot meet. The best is still to come.”

With the declaration, 92-year-old Biya, born February 13, 1933, became (currently) the world’s oldest person contesting political office. The Internet had not been officially born (January 1, 1983) when the Cameroonian leader took power on November 6, 1982 — 42 years ago! Ronald Reagan was President of the United States at the time. Since then, the US has had a lineup of six presidencies — George H. W. Bush (1989–1993), Bill Clinton (1993–2001); George W. Bush (2001–2009); Barack Obama (2009–2017); Donald Trump (2017–2021); Joe Biden (2021-2025) — and a seventh, being Trump’s second coming.

That President Biya professes a desire to lift his country’s fortunes is, in itself, commendable. Every leader ought to wish the best for their people. However, proclaiming “the best is still to come” after four decades on the saddle of governance suggests a rider who has either succumbed to unrealism or a nation-state so numbed by inept leadership that it can no longer envision renewal. While some may argue that Papa Biya has several more tricks up his political sleeve, the Cameroonian economy and other indicators seem to point to a downward slide.

Insecurity persists in the west and north, where secessionist movements and terrorism have led to the death and displacement of thousands. There is endemic corruption and high poverty, with 38 per cent of citizens living below the international threshold as of 2022. Alongside its autocratic regime, Cameroon ranked 136th out of 167 countries in the 2024 EIU Democracy Index. Its economy relies heavily on commodity exports, such as oil, making it vulnerable to fluctuations in global oil prices. Biya’s longevity has not been accidental; it is the product of deliberate constitutional engineering that dismantled checks on presidential power. In 2008, Cameroon’s parliament amended the constitution to abolish term limits, granting Biya and future leaders the legal cover for indefinite rule. That same amendment also provided immunity from prosecution after leaving office, insulating incumbents from accountability. These manoeuvres illustrate how institutions were weakened to serve the whims of one man, leaving little space for genuine democratic competition. Such systemic distortions have eroded public trust, deepened apathy, and normalised a culture of impunity in Cameroonian politics.

Ironically, several African nations share related challenges. However, Cameroon’s case bears a resemblance to a leadership that has deliberately opted to lock itself and its people into a vicious cycle of democratic hopelessness, demonstrating gross unwillingness to embrace positive change. The Biya administration has repeatedly stifled political opposition. Following the disputed 2018 presidential election, the main contender and runner-up, Maurice Kamto, was arrested on January 28, 2019, along with over 200 of his supporters. They were subsequently charged with multiple offences, including insurrection, before the charges were dropped. He was released on October 5, 2019, after approximately nine months in detention. In a further blow, the electoral commission, ELECAM, announced in July 2025 that Kamto’s candidacy for the upcoming October 12, 2025, poll had been rejected. The decision effectively silenced what little remained of the opposition’s already weakened and fragmented challenge.

The muted reaction of the international community has further emboldened Biya’s reign. Western allies often prioritise security cooperation in the fight against terrorism over pressing Yaoundé for reforms, while regional bodies such as the African Union frequently fall back on the principle of non-interference. This lack of sustained external pressure has allowed Biya to present himself as a bulwark of stability, even as his governance fuels instability at home. In the end, the world’s silence in the face of repression and democratic backsliding has functioned as tacit approval, leaving Cameroonians with little external leverage to force a political transition.

Unless Cameroon’s leadership casts aside its cloak of wilful amnesia and self-serving ambition, the country risks steering itself into a political storm. The Biya years may have held the nation together, preventing outright collapse, but that stability is little more than a façade. Millions of citizens — especially the young and energetic generation — have never been given a valid opportunity to conceive a credible alternative to President Biya. The deliberate suffocation of opposition has left Cameroonians wrestling with a troubling question: if not Biya, then who? Yet an even more unsettling question lingers: if Biya were suddenly gone, is the country truly prepared for what comes next? That appearance of national cohesion has not stemmed from any strengthening of democratic principles. Instead, it is the by-product of a circle of loyal political acolytes sustaining what some analysts describe as a frail figurehead at the Unity Palace in Yaounde. At the centre of this arrangement is Ferdinand Ngoh Ngoh, the Secretary-General to the President, who is widely believed to have assumed much of the president’s authority. He reportedly approves nearly every document requiring the head of state’s signature and has become the dominant face of governance, leading diplomatic missions, managing crises, and arbitrating disputes within the ruling Cameroon People’s Democratic Movement (CPDM): roles traditionally reserved for the president himself.

There does not appear to be a single remedy to pull Cameroon back from its hurtle toward the precipice of uncertainty. Beyond whatever pressure the international community may exert, the real solution to the country’s democratic stagnation rests with its people. Cameroonians must confront their reality and decide the kind of nation they wish to build. Rather than continue laying the bricks of political disaster, they must summon the courage to demand accountability, insist on transparent institutions, and reclaim their civic space.

As Biya seeks yet another term, the poser before Cameroon is whether a nation can reinvent itself after decades of arrested development. Real transformation will require citizens reclaiming their agency, rebuilding civic institutions, and insisting that leadership must serve the people, not entrench itself against them. Until then, Cameroon will remain trapped in a cycle where hope is postponed and the future mortgaged to one man’s ambition.