Without question, Nigeria’s examination bodies hold a pivotal, indispensable and irreplaceable role within the nation’s educational framework. They serve as the backbone for assessing learning outcomes, standardising academic achievement and safeguarding the credibility of certificates issued across all levels of education.

Beyond conducting examinations, these institutions help shape academic progression, determine access to higher education and employment opportunities, and reinforce public confidence in the education system. As such, their integrity, effectiveness and independence are critical not only to educational development but also to national growth and human capital advancement.

Nigeria’s major public examination institutions, including the Joint Admissions and Matriculation Board (JAMB), the West African Examinations Council (WAEC), the National Examinations Council (NECO), and the National Business and Technical Examinations Board (NABTEB), are far more than routine government departments or administrative outposts. They occupy a strategic and indispensable position within the nation’s education system as guardians of academic standards, arbiters of merit, and custodians of trust in how learning outcomes are assessed, admissions are determined, and certificates are awarded. Their work directly influences who progresses through the educational ladder and how Nigerian qualifications are regarded both locally and internationally.

The responsibilities of these bodies are not arbitrary. They are clearly defined in the statutes and legal instruments that brought them into existence, with mandates deliberately structured to protect Nigeria’s broader educational objectives. Central to these mandates is the commitment to fairness, transparency, uniformity, and credibility in the assessment of learners across the country. Through standardised examinations and regulated admissions processes, these agencies are meant to ensure that opportunity is earned through ability and preparation rather than privilege or manipulation.

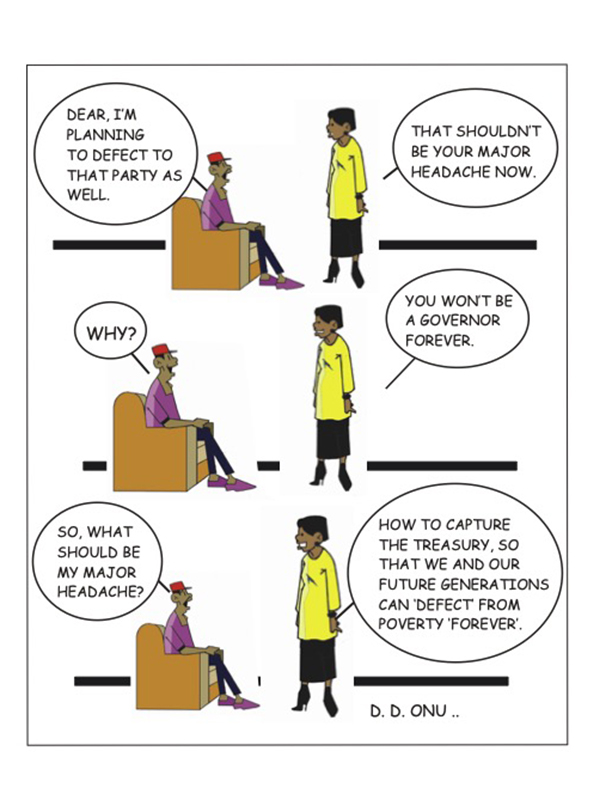

However, there are signs that pressures from outside the education sector, particularly political intrusions, are threatening to weaken the effectiveness and independence of these institutions, with potentially serious consequences for national standards.

Each examination body draws its authority and legitimacy from a specific legal framework. NABTEB, for example, was established under Decree 70, now Act 70, to focus on technical and business examinations. NECO was created in 1999 to conduct the Senior School Certificate Examination and expand Nigeria’s capacity for credible national assessment. JAMB was mandated to organise the Unified Tertiary Matriculation Examination, oversee admissions into tertiary institutions, and maintain a central admissions database that promotes equity and order in the transition from secondary to higher education. WAEC, operating as a regional organisation, conducts the West African Senior School Certificate Examination and issues certificates that are recognised not only across Anglophone West Africa but also in many parts of the world.

Although these bodies differ in scope and geography, their core responsibilities intersect. They are all involved in designing and administering examinations, certifying academic and vocational competence, maintaining standardisation and quality assurance, sharing essential admissions and assessment information, and continuously refining assessment techniques. Together, they form the foundation upon which Nigeria evaluates student preparedness for university education, skills acquisition, and participation in an increasingly competitive, knowledge-based global economy. Supporting this framework is the National Board for Educational Measurement, a professional institution charged with supervising assessment practices, validating test standards, and ensuring that both traditional and performance-based evaluations meet accepted benchmarks. Its existence underscores how seriously assessment integrity ought to be treated in a modern education system.

In recent years, the task facing examination bodies has become significantly more demanding. In addition to organising and marking millions of examination scripts across a vast and diverse country, these agencies are locked in a constant struggle against examination malpractice. What was once largely limited to impersonation and copying has evolved into a complex, technology-enabled enterprise involving parents, tutorial centres, schools, and even some computer-based test operators. This sophistication has forced examination bodies to rethink their strategies and invest heavily in modern tools and systems to protect credibility.

NECO’s experience illustrates the scale of this challenge. In an effort to curb impersonation and strengthen monitoring, the Council procured thousands of biometric machines and operational vehicles at a cost running into hundreds of millions of naira. Despite such investments, malpractice has not disappeared. During the 2025 Senior School Certificate Examination, NECO reportedly identified dozens of schools across multiple states involved in organised cheating, while several supervisors were recommended for sanctions due to misconduct ranging from aiding malpractice to insubordination. These incidents highlight how deeply entrenched the problem has become.

JAMB has faced similar pressures and has responded by continually upgrading its processes. Its examination systems now rely on multiple layers of technology designed to detect, deter, and prevent fraud. A special committee examining examination infractions even recommended the deployment of Artificial Intelligence to counter increasingly sophisticated malpractice techniques. The committee warned that cheating was becoming dangerously normalised, encouraged by weak enforcement frameworks and the involvement of multiple actors across the education ecosystem.

All of these measures come at a high cost. Advanced technology is expensive, nationwide logistics require substantial funding, and securing examination materials across thousands of centres demands careful planning and sustained investment. In such an environment, stability, concentration, and freedom from undue influence are not optional benefits but essential conditions for credibility. Examination bodies cannot effectively discharge their responsibilities if they are constantly distracted or destabilised by external pressures.

It is against this background that recent allegations of political interference have generated widespread concern. A coalition of civil society organisations has raised alarms over claims of intimidation and financial pressure involving the leadership of a legislative committee responsible for overseeing basic examinations. The groups allege that the oversight role has been used to exert pressure on the management of JAMB, WAEC, NECO, and NABTEB for financial contributions purportedly linked to committee activities. They further claim that these actions include irregular use of consultants, unilateral foreign trips funded through committee resources, and demands for sensitive financial documents from key government institutions, allegedly to coerce compliance from agency heads.

Questions have also been raised about substantial sums of money paid into and partially refunded from the committee’s account, with civil society actors calling for a transparent investigation. According to them, if such practices are allowed to persist, they risk reversing the progress examination bodies have made and eroding public confidence in the integrity of national assessments. They have therefore demanded decisive action, including leadership changes and accountability measures, warning that failure to act could provoke wider public protests. At the heart of their argument is the belief that institutions responsible for evaluating the futures of Nigerian children must be protected from intimidation, extortion, and political manipulation.

The financial implications of such interference do not end within the walls of these agencies. Ultimately, the burden is passed on to parents and students. Many Nigerian families already struggle to afford examination registration fees, and any additional strain on examination bodies, whether through diverted resources, forced contributions, or financial harassment, creates pressure to raise costs. Public examinations are meant to level the playing field, ensuring that progression is based on merit rather than wealth. Rising fees risk shutting out students from low- and middle-income households, deepening inequality and undermining the very rationale for standardised national assessments.

Another disturbing dimension of the situation is the relative silence of examination bodies in the face of alleged interference. While some may interpret this quietness as complicity, it more likely reflects institutional vulnerability within a system where power relations are uneven, and rules are not always applied consistently. When oversight becomes coercive, agency leaders may feel trapped, choosing discretion and survival over open resistance. Yet this silence carries its own risks, as it can embolden further interference and gradually normalise practices that threaten the integrity of public examinations. Agencies distracted by political pressure and financial demands cannot fully concentrate on fighting malpractice, investing in innovation, or maintaining public trust.

The stakes extend far beyond partisan politics or administrative disputes. The credibility of Nigeria’s examination system is a national concern. Certificates issued by JAMB, WAEC, NECO, and NABTEB determine access to higher education, vocational training, and employment, and they shape how Nigerian qualifications are viewed abroad. Nigeria also operates within a broader assessment environment that includes international examinations such as the International General Certificate of Secondary Education, commonly referred to locally as the Cambridge Examination. Nigerian students who take such exams often do so with the aim of studying overseas, where the integrity of assessment is non-negotiable. The coexistence of local and international assessment systems places an added responsibility on domestic examination bodies to uphold standards that can withstand global scrutiny.

Where allegations of intimidation or extortion arise, they cannot be dismissed as mere administrative disagreements. If proven, they point to ethical breaches and potential criminal conduct, making it appropriate for anti-graft agencies to step in. Legislative oversight is an essential component of democratic governance, but it must be exercised collectively, transparently, and strictly within the bounds of the law. It should strengthen institutions, not weaken them for personal or political gain. The National Assembly, therefore, bears responsibility for ensuring that its committees operate with integrity, competence, and a clear appreciation of the sensitivity of the sectors under their supervision.

At its core, the debate over external interference in examination bodies is a debate about Nigeria’s future. A country that aspires to economic competitiveness and social mobility cannot afford an assessment system compromised by greed, intimidation, or institutional fragility. Education remains one of the most powerful drivers of national development, and credible assessment is the backbone of that system. Examination bodies must be allowed to concentrate on their statutory duties: curbing malpractice, deploying modern technology, ensuring fairness, and sustaining public confidence. Any distraction from this mandate endangers not only institutions but also the aspirations of millions of Nigerian children whose futures depend on a trustworthy system of evaluation. Protecting these bodies from undue influence is, ultimately, about defending merit, equity, and the promise of education as a pathway to national progress.

AGBAJILEKE, a journalist and public affairs analyst, writes from Abuja.