At a time that military adventurism seems to threaten democratic stability in the West African region, the seamless transition featured in the recent general election held in Liberia presents a positive outlook to civil rule and offers deep lessons to African leaders with a sit-tight mentality. The Liberian election was held to elect a new President, and members of the National Parliament.

As with most elections in Africa, there was palpable tension and fear of the power of incumbency, and sundry imaginations that something could go wrong. However, Liberians proved book makers wrong. Perhaps, lessons of two civil wars sank into the psyche of the population that avoided the tipping point.

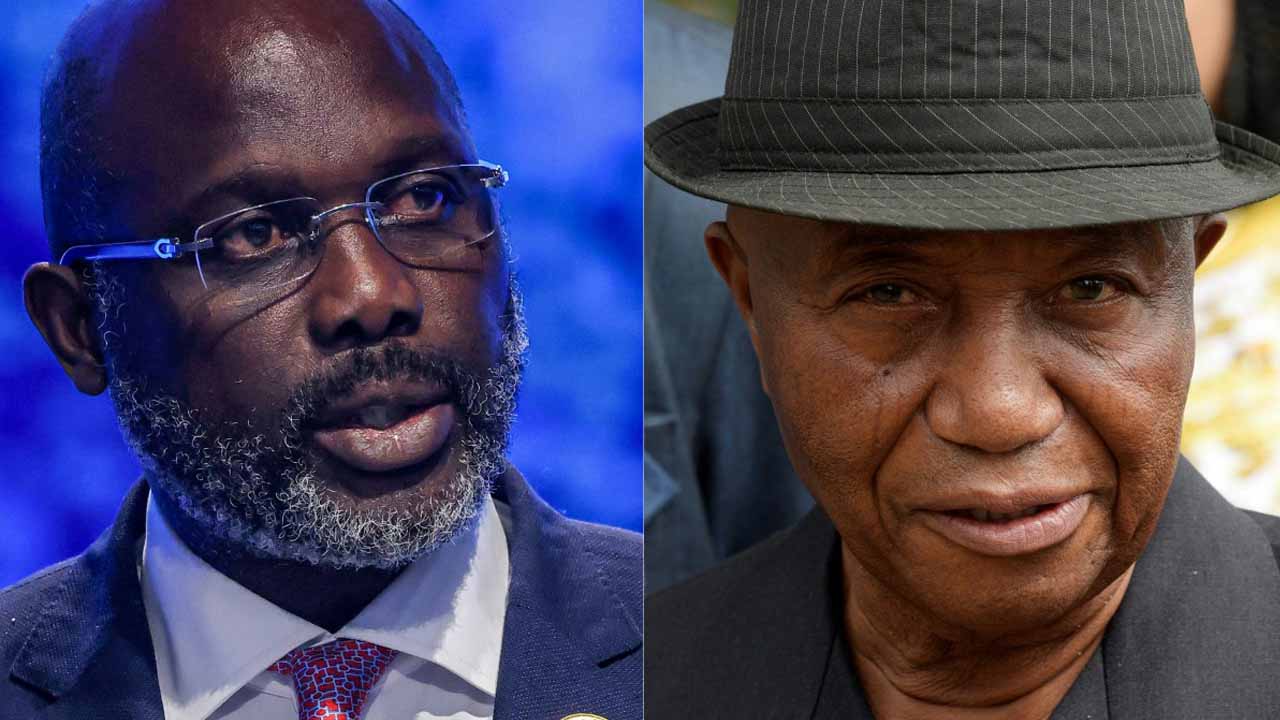

The election was the fourth since the end of the civil war, and was keenly contested, to the extent of a run-off in which the incumbent accepted defeat, even before the final tally, thereby edifying the Liberian democracy. Two major gladiators contested the election, namely, incumbent George Weah of the Congress for Democratic Change (CDC), and Joseph Boakai of the Unity Party (UP).

The first round of the election was held on October 10, and Weah polled a slim lead at 43.83 per cent of the vote, while Boakai had 43.44 per cent. The inability of either of the two frontrunners, President George Weah, and opposition leader Joseph Boakai, to secure enough votes, sparked off the motion towards a re-run.

The re-run held as scheduled and Joseph Boakai polled 50.89 per cent and President Weah, 49.11 per cent. In ways edifying, Weah accepted defeat while the vote count had yet to be completed in the November 14 re-run elections. The opposition was in a comfortable lead with 28,000 votes, a thoughtful Weah accepted defeat with the exemplary words “The Liberian people have spoken and we have heard their voice.” By this singular act, he opened up a new chapter in Africa’s electoral history, building on Nigeria’s Goodluck Jonathan concession in 2015.

Weah assumed power in Liberia in 2017 in an election in which he defeated the current victor, Boakai, with about 60 per cent of the votes rising on the waves of discontent over the patrimonial regime of Ellen Sirleaf who misgoverned the country, making it an appendage of the west and even volunteered to host the U.S. Africom at a time of Africa-wide opposition to the proposal. Besides, he appointed her children into vital government positions in a rapid expression of patrimonialism. Her son, Charles Sirleaf, was made the Governor of the Liberian Central Bank; the second son, Robert Sirleaf, was chief executive of the National Oil Company of Liberia, and the third son, Fombah Sirleaf, was head of the National Security Agency, the body responsible for internal security.

Sirleaf left behind an impoverished Liberia, the wave upon which Weah rose to power. Weah’s inability to manage the situation six years after, became his Achilles heels. He had essayed at populist approach to governance with a pay cut, revision of the school curriculum, capping of salaries of government officials at $7,800 and the Land Rights Act that delineates categories of land ownership.

Nevertheless, inflation spiked at over 20 per cent, and there was delay in the payment of salaries. The poverty rate increased with outbreaks of epidemic, such as Ebola and COVID-19. Over half of the 5.4 million population who live below the poverty line, were further traumatised, resulting in street protests. As many predicted, these social realities impacted the electoral outcome.

Customarily, the conduct of the election has attracted commendation from the election observers. The observers from the Economic Community of West African States noted “the generally peaceful conduct of the elections so far.” The European Union saw improvement in the election. In its preliminary statement, it noted that “Our 85 election observers reported from 326 polling places in rural and urban areas in all 15 counties and 63 out of 73 districts. EU EOM observers assessed the conduct of the voting process in observed polling stations as very good. Procedural irregularities were reduced in the run-off also thanks to a refresher training programme for the polling personnel organised by the National Elections Commission.”

There are a lot of lessons to be learnt from the Liberian election, seen as a test for democracy by sundry observers, and whose outcome has attracted a number of epithets, such as “Africa Rising” and “a breath of fresh air.” Indeed, it is somewhat an exceptionalism in a sub-region racked by coup d’états. A sportsmanship approach to politics can aid democratic consolidation and stability. For an election that finished with a narrow 49.36 per cent to 50.64 per cent margin, it could easily have been manipulated in a continent where incumbents do not organise elections to lose. As a commentator has rightly noted, “Weah wasn’t lacking in bad examples to follow. Guinea, Liberia’s northern neighbour, is under military rule, as are nearby Mali and Burkina Faso. Except for the late Jerry Rawlings of Ghana who exited at 53, African statesmen hardly retire at 57 or even 75 for that matter. The relics in Cameroon, Uganda and Equatorial Guinea are worth counting.”

Weah has blazed an exemplary path by his acceptance of defeat. Sit-tightism would obviously have compounded Liberia’s fragility, but his condescension and acceptance of defeat, offers the country a lease to face its numerous social problems. Besides, it offers the continent a worthy example of statesmanship, and subordination of personal interest to the general.

The victor, Mr Boakai, should discern from the tight race problematic faultlines, which he must address. The results, somehow, are indicative of a divided country. He must avoid the winner-takes-all inclination, and carry every segment of the Liberian society along in the task of nation-building and the share of reward. Also, he must unite the country and implement the unimplemented report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission since 2009.