In a world of increasing financial complexity and economic instability, bank failure readiness is no longer a luxury but a necessity. Whilst Nigeria has taken strides in stabilising its banking sector since the 2009 crisis, many challenges persist.

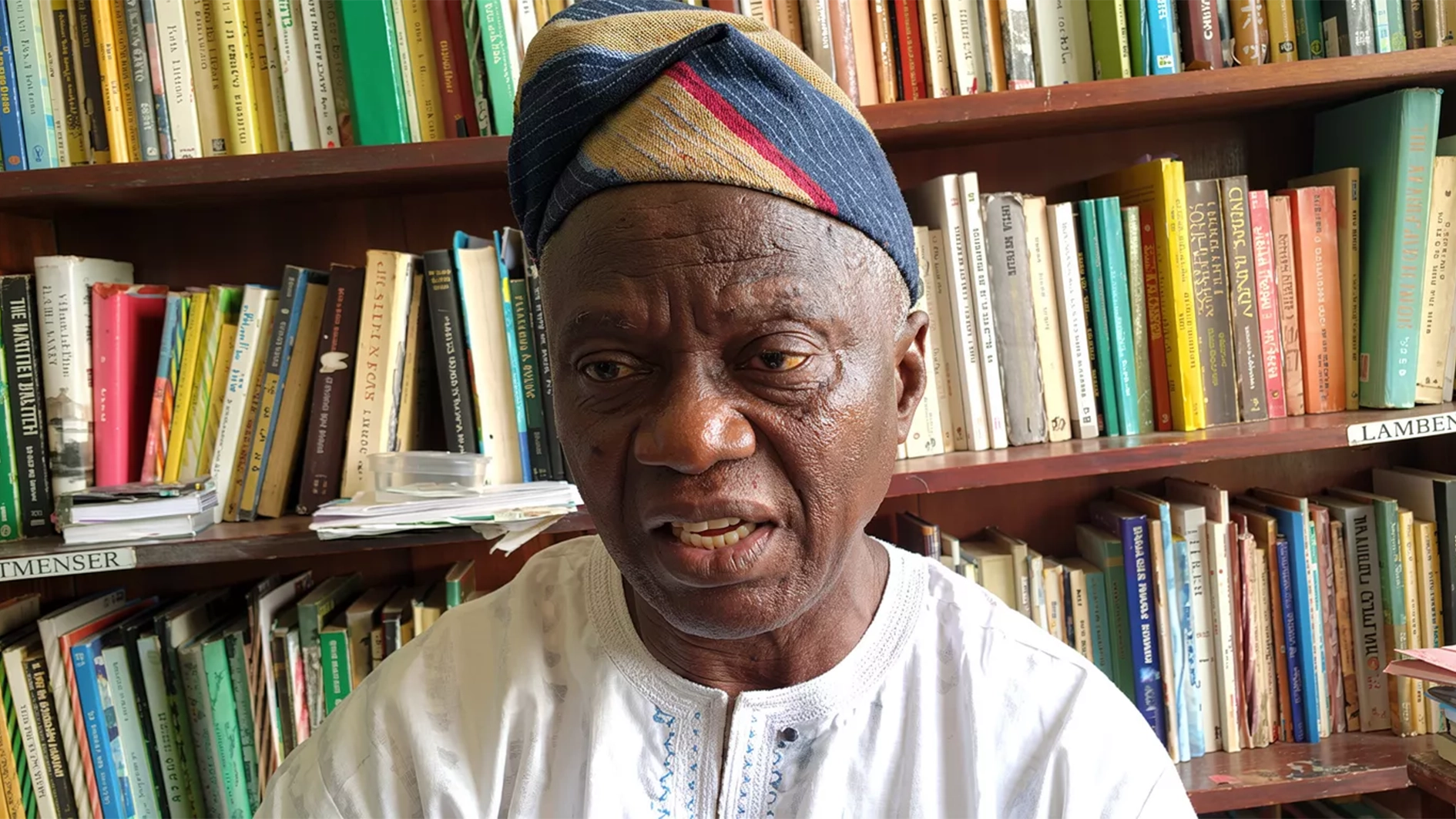

In this exclusive online interview with Gifty Aiyegbeni, a Nigerian data scientist and analyst currently working at the Financial Services Compensation Scheme (FSCS) in the United Kingdom, she explains how Nigeria can learn from the UK’s proactive approach to financial system protection. She previously worked as a financial analyst at one of Nigeria’s reputable financial services companies, Afrinvest (West Africa) Limited, which gives her solid understanding into Nigeria’s financial systems.

With a professional background that intersects financial analytics, data science, machine learning, regulatory compliance, and financial safety net frameworks, Gifty offers unique insights into how Nigeria can build a more resilient banking system.

Tell us a bit about FSCS and your current role.

Thank you for having me. The Financial Services Compensation Scheme (FSCS) is the UK’s deposit insurance and financial protection body, similar to NDIC in Nigeria. It compensates customers when financial institutions fail, which is currently up to £85,000 per person, per institution. At FSCS, I work as a Data Assurance Analyst, where I conduct regulatory reviews and data quality checks. My job involves analysing financial institutions’ data for red flags, ensuring compliance with UK regulations, and supporting early detection of financial distress through data-driven processes and many more.

How important is data governance in preventing or mitigating bank failures?

Extremely important. Poor data governance can blind regulators to early warning signs. At FSCS, data integrity, transparency, and ethical use are central to everything we do. Nigeria needs to prioritise standardised reporting, ensure that banks submit accurate and timely data, and train more professionals in data auditing and regulatory analytics.

Many Nigerians are still sceptical about regulatory effectiveness. What would you say to policymakers and the public?

I’d say build trust through consistency and transparency. Policymakers must invest in systems that don’t just react when there’s a failure but are constantly evaluating risk and preparing for it. The public also needs to be better informed about what protections are in place and how they can access support if their bank fails. Trust is built on communication, and that’s an area Nigeria can strengthen.

How can Nigeria better support small banks and microfinance institutions in building financial resilience?

Nigeria must recognise that small banks and microfinance institutions serve a vital role in financial inclusion. These institutions often lack the resources for strong internal risk monitoring, so regulatory bodies should provide tailored guidance and subsidised access to compliance tools and training. It’s not enough to regulate; they should also support and uplift these players so they can operate safely and sustainably.

From your vantage point, what are some key strategies Nigeria could adopt from FSCS to improve its readiness for potential bank failures?

There are several, but I’d highlight these three:

1. Bank Data Testing Systems:

One of the key lessons from the FSCS is the importance of data testing systems that allow banks to proactively assess the quality of their own data. In the UK, banks are required to participate in regular data testing to ensure their customer records are complete, accurate, and ready for use in the event of a failure. Nigeria could implement a similar framework where banks use standardised tools to evaluate the accuracy and reliability of depositor information. This not only improves internal data governance but also ensures that, should a failure occur, a payout can be made swiftly and efficiently with minimal errors.

2. Data Testing Drills and Grading:

In addition to internal data testing, FSCS organises structured data testing drills where selected banks are assessed on their readiness to provide clean, actionable data in case of default. These exercises simulate real payout conditions, and banks are graded based on how well their data performs under pressure. Nigeria can adopt this model through periodic drills led by the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) or the Nigeria Deposit Insurance Corporation (NDIC), helping to measure and improve the operational readiness of each institution. The grades can serve as indicators of a bank’s stability and preparedness, enhancing transparency for both regulators and the public.

3. Public Awareness and Speedy Compensation:

Many UK consumers are aware of the FSCS guarantee, and payouts are typically made within seven days. Nigeria’s NDIC has a similar role but could improve public trust by increasing awareness and automating compensation using the Bank Verification Number (BVN) system. This would reduce panic and restore confidence quickly in case of a crisis.

Could fintech collaboration help improve bank failure response mechanisms in Nigeria?

Yes. Fintech companies can support real-time monitoring, identity verification, and faster disbursement of compensation. In the UK, there is growing collaboration between financial regulators and the fintech ecosystem to modernise safety nets. We are currently working on improved payment methods to better satisfy customers. Nigeria should follow this lead. In Nigeria, fintechs can provide data infrastructure and innovation, whilst regulators ensure it aligns with public interest.

Given your background, do you see yourself contributing more directly to Nigeria’s financial system in the future?

Absolutely. I remain deeply connected to Nigeria and am always open to collaboration, be it through research, policy advising, or training programmes. My long-term vision includes helping to shape risk management practices and data frameworks in Nigeria’s financial sector by advancing data-driven innovation to enhance financial integrity, regulatory compliance, public sector accountability, the promotion of data transparency, the protection of financial consumers, and the advancement of sustainable, tech-enabled governance systems, especially in underserved areas. We have the talent; we just need stronger systems and better coordination.

Do you have any final words for Nigeria’s financial institutions?

Yes, don’t wait for a crisis to take action. Nigeria must move from crisis response to prevention. The cost of prevention is far less than the cost of rescue. Let’s embrace smart data, strategic collaboration, and public engagement to build a safer, more reliable banking system for all Nigerians.