*Physical activity changes the metabolism of the immune system’s cytotoxic T cells, thereby improves their ability to attack tumour cells

New research has suggested that people who exercise early morning may have a reduced risk of developing cancer than those who exercise later in the day.

The research, appearing in the International Journal of Cancer, may help inform future research into the timing of exercise as a potential way of reducing cancer risk.

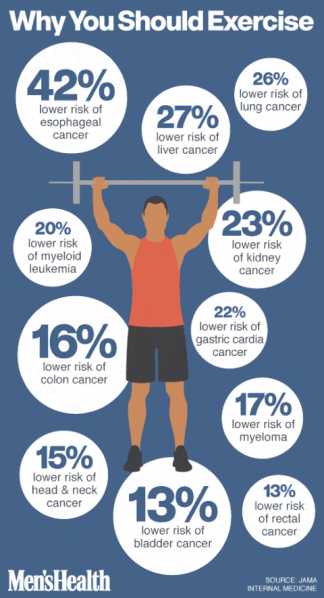

Research has shown that doing recreational exercise can reduce a person’s risk of developing many different cancers.

This information is important because of the high number of people who develop cancer and the significant number who die of the disease. For example, in the United States, scientists estimate that by the end of 2020, 1,806,590 people will receive a diagnosis of cancer, while 606,520 people will die from the disease.

Given the large numbers of people who develop cancer, even a change as small as changing the time a person exercises could make a significant contribution to reducing the impact of cancer across the whole population.

As of 2018, 46.7 per cent of adults in the U.S. did not meet the minimum aerobic physical activity guidelines. Increasing physical activity and optimizing when it is most effective might be a possible way of reducing the prevalence of cancer in society.

There is also evidence that a person’s circadian rhythm may have links to their chance of developing cancer. The phrase circadian rhythm refers to the biological processes that affect a person’s sleep-wake cycle.

The International Agency for Research on Cancer has classified the level of evidence linking night shift work that disrupts a person’s circadian rhythm as “probably” carcinogenic to humans.

In particular, researchers have linked night shift work to an increased risk of breast cancer. The evidence for prostate cancer remains unclear.

Scientists have shown that exercise also has a relationship with a person’s circadian rhythm. According to 2019 research, exercising during the day may help improve a person’s circadian rhythm and lessen the adverse effects of disrupted sleep patterns.

Given that exercise can potentially reduce the risks of cancer and improve circadian rhythms and disrupted circadian rhythms can increase cancer risk, the authors of the new research hypothesized that the timing of physical activity might affect cancer risk.

To test this hypothesis, the researchers behind the present study analyzed the data from 2,795 participants. The participants were a subset of the Spanish multi case-control study (MCC-Spain), which set out to understand factors causing common cancers in Spain and how to prevent them.

From 2008–2013, researchers interviewed the participants to find out their lifetime recreational and household physical activity. An average of 3 years later, researchers assessed the timing of when people exercised.

The researchers looked in particular at the 781 women who had breast cancer and also responded to the questionnaire about their physical activity and 504 men who had prostate cancer and provided data about the timing of their exercise.

The researchers chose the controls in the MCC-Spain study randomly from general practice records. The researchers matched them to people in the study with cancer who were of the same sex and similar age. The controls in this study also responded to the follow-up questions about physical activity and its timings.

The researchers found that physical activity between 8:00 a.m. and 10:00 a.m. had the strongest potential beneficial effect at reducing breast and prostate cancer.

About seven per cent of the people with breast cancer and nine per cent of people in the control group undertook most of their exercise in the early morning. About 12.7 per cent of people with prostate cancer and 14 per cent of the control group did early morning exercise.

The researchers developed a model that showed that the odds of developing breast cancer were potentially 25 per cent lower due to exercising in the morning compared with not exercising.

However, the statistical confidence of this estimate ranges from a 52 per cent reduction to a 15 per cent increase in risk.

The results show a similar picture of prostate cancer. The model predicted that those who exercised in the early morning had a 27 per cent reduced chance of having prostate cancer than non-exercisers. However, the range went from a 56 per cent reduction to a 20 per cent increase.

People who exercised in the evening, between 7:00 p.m. and 11:00 p.m., had a 25 per cent reduced risk for developing prostate cancer. However, as with the early morning findings, the evidence is not statistically significant.

The researchers suggest that any beneficial effects of early exercise for breast cancer risk may have links to estrogen. High estrogen levels have associations with an increased risk of breast cancer, and exercise can lower estrogen levels. Further, estrogen production is most active at around 7:00 a.m.

Melatonin may also be a factor. Researchers have shown that melatonin may protect against cancer risk and that exercise later in the day or at night can delay melatonin production.

MEANWHILE, another study has shown that people with cancer who exercise generally have a better prognosis than inactive patients. Now, researchers at Karolinska Institutet in Sweden have found a likely explanation of why exercise helps slow down cancer growth in mice: Physical activity changes the metabolism of the immune system’s cytotoxic T cells and thereby improves their ability to attack cancer cells.

The study is published in the journal eLife.

“The biology behind the positive effects of exercise can provide new insights into how the body maintains health as well as help us design and improve treatments against cancer,” said Randall Johnson, professor at the Department of Cell and Molecular Biology, Karolinska Institutet, and the study’s corresponding author.

Prior research has shown that physical activity can prevent unhealthy as well as improve the prognosis of several diseases including various forms of cancer.

Exactly how exercise exerts its protective effects against cancer is, however, still unknown, especially when it comes to the biological mechanisms. One plausible explanation is that physical activity activates the immune system and thereby bolsters the body’s ability to prevent and inhibit cancer growth.

In this study, researchers at Karolinska Institutet expanded on this hypothesis by examining how the immune system’s cytotoxic T cells, that is white blood cells specialized in killing cancer cells, respond to exercise.

They divided mice with cancer into two groups and let one group exercise regularly in a spinning wheel while the other remained inactive. The result showed that cancer growth slowed and mortality decreased in the trained animals compared with the untrained.

Next, the researchers examined the importance of cytotoxic T cells by injecting antibodies that remove these T cells in both trained and untrained mice. The antibodies knocked out the positive effect of exercise on both cancer growth and survival, which according to the researchers demonstrates the significance of these T cells for exercise-induced suppression of cancer.

The researchers also transferred cytotoxic T cells from trained to untrained mice with tumors, which improved their prospects compared with those who got cells from untrained animals.

To examine how exercise influenced cancer growth, the researchers isolated T cells, blood and tissue samples after training sessions and measured levels of common metabolites that are produced in muscle and excreted into plasma at high levels during exertion.

Some of these metabolites, such as lactate, altered the metabolism of the T cells and increased their activity. The researchers also found that T cells isolated from an exercised animal showed an altered metabolism compared to T cells from resting animals.

In addition, the researchers examined how these metabolites change in response to exercise in humans. They took blood samples from eight healthy men after 30 minutes of intense cycling and noticed that the same training-induced metabolites were released in humans.

“Our research shows that exercise affects the production of several molecules and metabolites that activate cancer-fighting immune cells and thereby inhibit cancer growth,” said Helene Rundqvist, a senior researcher at the Department of Laboratory Medicine, Karolinska Institutet, and the study’s first author. “We hope these results may contribute to a deeper understanding of how our lifestyle impacts our immune system and inform the development of new immunotherapies against cancer.”