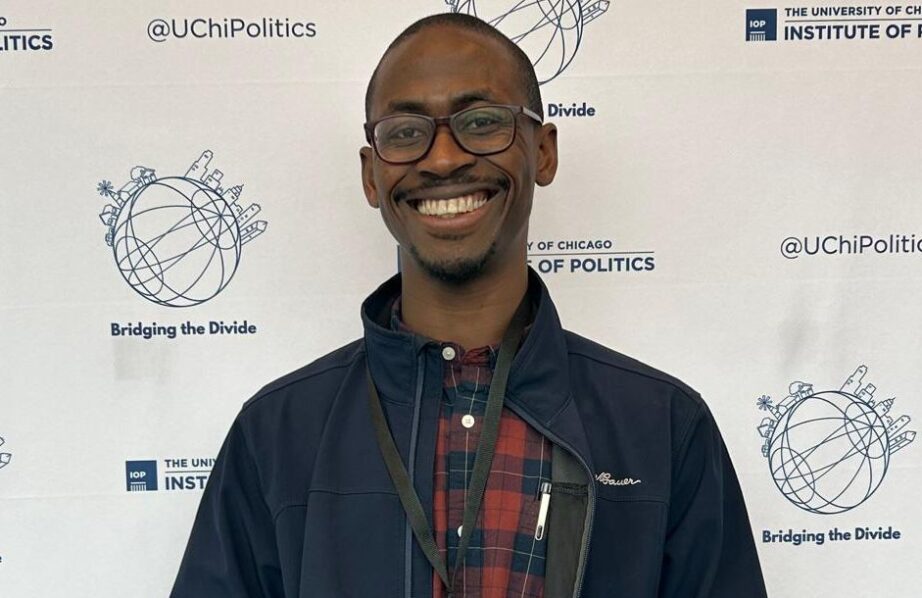

In a groundbreaking advancement for evidence-informed policymaking, Toyib Aremu, a doctoral researcher at the University of Vermont, is revolutionising how researchers engage with science to shape public policy. Aremu’s work, which is drawing attention globally, underscores his role as a leading voice in bridging the critical divide between scientific research and policy application, especially in Nigeria’s agricultural sector.

Policymakers often face criticism for not basing their decisions on sound scientific evidence. However, Aremu’s research sheds light on an overlooked issue: whether researchers produce science in ways that make it accessible and actionable for policymakers. “If policymakers are criticised for not using the best science, it’s crucial to ask whether researchers are creating this science in ways likely to be used by decision-makers,” Aremu explains. “This study addresses a key question: if evidence syntheses provide a more objective source for policymaking, are researchers producing them in ways that encourage policymakers to use them?”

Aremu’s recently published paper, “Towards Evidence-Informed Policymaking in Nigeria,” highlights important gaps in the use of evidence within Nigerian agricultural policy. “One major finding is that there are very few evidence syntheses on agriculture in Nigeria,” Aremu notes. “And those that do exist mostly focus on identifying policy problems rather than proposing solutions or strategies for implementation. This limits science’s impact on the decision-making process.”

Policymakers, he points out, prefer research that includes actionable statistics, such as the economic impact of a given policy solution. However, he found that Nigerian researchers often lack the primary data necessary to conduct quantitative syntheses, underscoring the need for more primary studies and consistent metrics. Aremu also calls for Nigerian universities to provide more targeted training to help researchers effectively communicate their findings to policymakers.

Aremu believes that building stronger partnerships between researchers and policymakers is crucial. “Our study shows that there is limited collaboration, suggesting that both parties often work with different goals and approaches,” he says. “Most syntheses we reviewed aimed to address research gaps rather than solve specific policy issues. However, if researchers and policymakers worked more closely, researchers could tailor their work to policy priorities and share findings directly with relevant policymakers.”

The significance of Aremu’s work goes beyond his study’s findings. His paper offers practical recommendations to bridge the science-policy divide in Nigeria and beyond. “Researchers must understand that a policy audience differs from a research audience,” he advises. “Communicating findings might mean publishing news articles in accessible language or crafting clear, actionable recommendations in their papers, so policymakers can grasp the implications immediately. I also urge funding bodies to support evidence syntheses, especially those focused on policy solutions, implementation, and effectiveness evaluations.”

Aremu’s study serves as a vital call to action for Nigerian research institutions, universities, funding partners and policymakers to work together and elevate the role of science in policymaking, ensuring decisions are not only informed by evidence but also effective and impactful.