• Becoming VC Was Divine Assignment, Not Ambition – Babalola

• Warns That Over-Reliance On AI Can Destroy Creativity, Weaken Minds

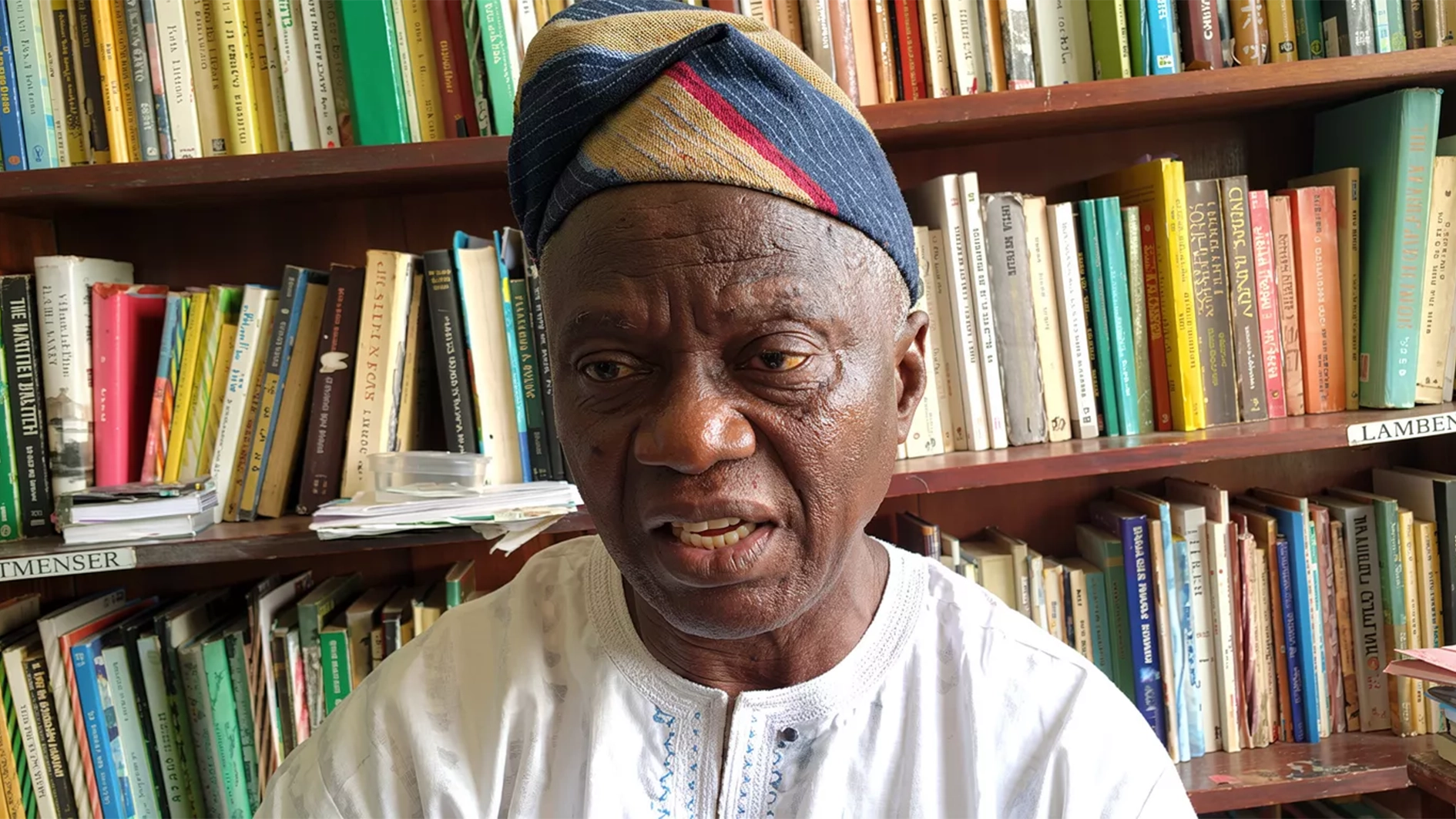

Prof. Jonathan Oyebamiji Babalola is the Vice Chancellor of Bowen University, Iwo, Osun State, one of Nigeria’s foremost faith-based private universities. A Professor of Chemistry at the University of Ibadan, he is also the immediate past Provost of the Postgraduate College of the same university, a Fellow of the Nigerian Academy of Science and several prestigious scientific societies, in this interview with ROTIMI AGBOLUAJE, he speaks on his journey to Bowen University, the difference between private and public tertiary institutions, the moral and financial realities of managing a private university, the crisis in Nigeria’s higher education sector, and his reflections on Artificial Intelligence and the future of learning and other issues.

You’ve spent most of your career in the public university system. How would you describe the system?

HONESTLY, our public universities are in serious distress. Funding is poor, infrastructure is decaying, and morale is very low. When a full professor earns less than $400 a month, it is discouraging. In 2016, when I briefly visited Germany on sabbatical, my salary at home was about $1,500 per month, not great, but manageable. Today, it’s less than a third of that in real value. That’s tragic. How can a professor who can’t afford decent accommodation or proper research tools give his best? It’s almost as if some people want to kill the public university system. If that is the case, then the government has a duty not to let it happen. A nation’s intellectual and technological future rests on its universities. When you walk through some laboratories in public institutions today, you will weep. Equipment is obsolete, chemicals are expired, and power supply is erratic. We have expanded the system too fast, creating more universities than we can fund. Quantity has replaced quality. It would be better to have 30 well-funded universities than 200 glorified secondary schools. Let’s build strong, functional institutions, not just tick boxes for political gain.

What must Nigeria do to revive the system?

First, our leaders must understand that education is a long-term investment. You can’t plant today and harvest tomorrow. Nations like Malaysia, China, and Singapore spent decades investing consistently in education before seeing results. In Nigeria, we want instant dividends. We want to invest in January and harvest by December. It doesn’t work that way. Education demands vision, patience, and sustained commitment.

Government must fund research, restore laboratories, improve staff welfare, and prioritise merit. And we must stop spreading our resources too thin. It’s better to have a few excellent universities than a hundred that barely function. The goal should be quality over quantity.

Some people believe that lecturers in private universities are less qualified than those in public universities. How would you react to this?

That perception is completely false. In fact, I would argue that many private universities, including Bowen, are setting higher standards.

Let’s take professional performance as an example. Many Bowen students complete professional qualifications such as Institute of Chartered Accountants of Nigeria (ICAN) before graduating with their Bachelor’s degrees. How many public university students achieve that?

At the Nigerian Law School’s last convocation, out of 4,429 graduating students nationwide, Bowen produced two first-class graduates, placing one of our students as the fourth best in the country for law education.

In research, the story is even more impressive. According to Scopus, one of the world’s leading databases for research impact, 13 Bowen scholars were listed among Nigeria’s top 500 scientists in Nigeria. Stanford University’s global ranking of the top two per cent of scientists in the world for 2024 included seven Bowen faculty members. Tell me, how many public universities can boast of those numbers? Apart from, perhaps the University of Ibadan, University of Lagos, and Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, very few come close. So, the notion that private universities employ inferior academics is not only wrong but outdated. Our staff are productive, our students are motivated, and our outcomes speak volumes.

The campaign for the extension support to private universities by the Federal Government has been on for some time now. Why is this necessary considering the fact that private universities are private entities that are out to make a profit?

The idea that the government should only support public universities is outdated. Remember, the students in private universities are also Nigerians, and their parents pay taxes too. There is a wrong assumption that all private university students come from wealthy homes. That is far from reality. I know students in Bowen who struggle to pay tuition, some who eat once a day, and others whose extended families contribute to keep them in school.

Education is critical. If private universities are producing well-trained graduates, contributing to research, and helping to develop the country, why shouldn’t they receive at least some form of institutional or research grant?

It doesn’t have to be cash transfers. The government can provide laboratory equipment, research funding, or scholarships for students in private universities. These are national investments. The ultimate beneficiaries are Nigeria and Nigerians.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has gained currency in the intellectual circle and other human spheres. Does your university, Bowen University, have a policy on Artificial Intelligence (AI)?

Yes, we do, and we’re constantly refining it. AI is a reality we can’t ignore, so we’ve integrated it into our ICT and academic integrity policies.

Our philosophy is simple: AI should be used as a tool for creativity, not as a substitute for originality. Students and staff can use AI to generate ideas, analyse data, or improve efficiency, but they must not present AI-generated content as their own.

We use Turnitin software, which now detects both plagiarism and AI-generated text. Our acceptable similarity index is around 24 per cent. Any AI assistance must be properly acknowledged, just like any other source. What we discourage is intellectual laziness, using machines to do what your brain should do.

What do you think are the broader implications of AI for young people?

AI is a double-edged sword. It can accelerate progress, but it can also destroy human creativity if misused. When we were young, we solved problems through reasoning and hard work. Today, many students reach for calculators or ChatGPT the moment they encounter a challenge. That weakens the mind. God gives us intellect and imagination so that we can think, innovate, and create. If we stop using those gifts, they atrophy. Dependence on machines reduces our mental sharpness and emotional resilience.

Moreover, AI can be dangerous. It can fabricate information, generate fake videos or voices, and distort reality. Someone could create a video of me ‘saying’ things I never said, and it would look authentic. That’s how perilous this technology can be in the wrong hands.

So, while I embrace AI as a scientific breakthrough, I also advocate caution. We must train our students to use it responsibly, ethically, and transparently. AI should serve humanity, not replace it.

You have now spent over two years as Vice Chancellor. How has the experience been?

It has been both challenging and deeply fulfilling. I thank God for the opportunity to serve, and I am immensely grateful to the Nigerian Baptist Convention, the President, the Pro-Chancellor, and the Governing Council, for giving me the privilege to lead Bowen University.

One of the first things I discovered is that there is a huge difference between being a Vice Chancellor in a public university and serving in a private, faith-based institution. In public universities, the VC is largely removed from the day-to-day life of students. There are tens of thousands of them, and it’s nearly impossible to know their individual challenges.

On the flip side, in a private university like Bowen, it’s completely different. Here, the Vice Chancellor plays the role of a father figure. When a student falls ill, I get to know. When there’s a disciplinary case, it usually lands on my desk. You are not just an administrator; you are a shepherd, a guide, sometimes even a counselor. The workload is enormous because you are directly responsible for everything, from academic administration to funding, discipline, welfare, and moral instruction. Yet, the satisfaction is immense. I can talk openly to students about Christ, morality, and integrity, something that would be difficult in public universities. In public institutions, you can still promote good values, but you have to be careful about how you do it.

Of course, finances are a major constraint. We don’t receive government subventions, so we have to manage our limited resources prudently. But even with the challenges, there is joy in seeing lives transformed, intellectually, morally, and spiritually. That, for me, is true fulfillment.

What major challenges does Bowen University face?

The foremost challenge is funding. If we had the kind of financial resources that public universities receive from the government, there is so much more we could achieve. Bowen University operates under the Nigerian Baptist Convention, so while it is a mission institution, it must also be self-sustaining. That balance is delicate.

When people hear that private universities charge tuition, they assume we are in money. That’s not true. Most of the income goes into salaries, maintenance, and facilities. If the government were to pay our staff salaries while we use our internally generated funds for infrastructure and innovation, Bowen would be miles ahead of where we are today.

Another challenge is the diversity of our student body and the expectations that come with it. Parents send their children to private universities for different reasons. Some want stable academic calendars; no strikes, and no disruptions. Others are motivated by moral reasons. They fear their children might be negatively influenced in public institutions.

There are also parents who know their children have behavioural issues and want an environment that can reform them. Some live abroad and send their children to Bowen because they want a safe, structured, and morally sound university at home in Nigeria.

All of this diversity creates challenges. Some of our students come from humble backgrounds and are well-behaved. Others come from very wealthy families, used to getting everything they want. We jokingly call it the “rich man’s child syndrome.” Some of these students drive cars at home, and when they get here and are told they cannot, they struggle with discipline.

But we have a strong spiritual structure, chaplaincy, counseling teams, and mentoring programmes. Over time, many of these students change. I have seen remarkable transformations. That is why I always tell people: private universities are not havens for spoilt children. They are reformative environments that produce disciplined, well-rounded individuals.

Why did you apply for the position of Vice Chancellor at Bowen University?

To be honest, Bowen University was not in my original plan. After serving for six years as Dean and then as Provost of the Postgraduate College at the University of Ibadan, my intention was to take a break, perhaps, take up a short-term United Nations research assignment or make use of one of my long-standing fellowships abroad. That was the plan. But, when the advertisement for the position of Vice Chancellor at Bowen University came out, several colleagues, mentors, and even friends encouraged me to apply. Initially, I was reluctant. I prayed about it, asking God for a clear direction, either a “yes” or a “no.” What I received, however, was neither. Instead, I felt a deep sense of persuasion, a conviction that God had a purpose for me at Bowen. That spiritual nudge changed everything. I realised that this was not just another administrative position; it was an assignment. And so, I applied, not out of ambition, but out of obedience.

Are you a pastor?

I am a Baptist by faith and upbringing. I was born into a Baptist family and have remained in the denomination all my life. However, I am not a pastor, I am a deacon and teacher. In the Baptist tradition, pastors must go through formal theological training in the seminary, and I have not done that. My calling is to teach, mentor, and guide, both in academics and in life. That is how I see my service.

What will be your message for Nigerians and friends of Bowen University?

First, I thank God for His faithfulness to Bowen University. I also appreciate the Nigerian Baptist Convention and all members of staff who share our vision of producing graduates who are not only intellectually sound but morally upright and spiritually grounded.

I want to appeal to well-meaning Nigerians, individuals, churches, organisations, and alumni to invest in human capital development. There are brilliant students who struggle financially. Supporting them is one of the noblest investments anyone can make.

Education is not a business; it is a ministry of transformation. The returns may not come immediately, but they are eternal. I thank the federal government for granting Bowen University its operating license and for the recognition we continue to receive nationally and internationally. We remain committed to our mission: to raise godly, competent, and visionary leaders for Nigeria and the world.