One of the most interesting features of Nigeria’s political environment is the rate at which it generates concepts, idioms and neologisms that populate the political lexicon and one way or the other explains Nigeria’s peculiar political situation. From “Wetie” introduced during the first republic and the turbulent period of the “Wild Wild West” to depict the critical political chaos in the old Western region, to “Siddon look,” the late Bola Ige’s concept for a political temperament of critical silence, we have had series of words and terms that all seem to speak, with inerrant accurateness, to our political predicament. The third world, and especially Africa, is a site of political and socioeconomic turmoil that current and contemporary theories and ideas seem to find difficult to come to terms with. This is a postcolonial context that does not just answer to Western political labels and theories. This is because it generates its own uniqueness, together with the features that other political contexts in the world share with it.

Thus, when in 2014, the former governor of Ekiti state, Ayodele Fayose, gave life to the phrase “stomach infrastructure,” it appeared like any other phrase or concept in our political lexicon. It has enjoyed its own period of derisive laughter, and it has also been thrown about as a characterization of bad policy and governmental action. But just as I mentioned earlier, these various items in Nigeria’s political lexicon have a way of describing some aspects of our political reality in ways that theoretical and intellectual terms and concepts may not. This is because they are derived from within the complexity of our postcolonial political unraveling in all its positive and negative manifestations.

When Fayose threw the phrase into the public sphere, it was in an attempt to undermine his political opponents through a populist tactics that plays to the existential and infrastructural needs of the people. The first manifestation of this phrase was in 2003 when Fayose made his first appearance as the challenger of the incumbent governor Niyi Adebayo. He deployed tankers throughout the state to provide surplus water to everyone (in a city where the water infrastructure was almost absent). Either through this singular act or a collection of other variables, Fayose won the election then. And then in 2014, he was around again, and he again unseated the incumbent Governor Kayode Fayemi. This time around, Fayose did not deploy water but rather essential commodities like rice, chicken and some naira notes to “empower” prospective voters in the right direction. Well, the Ekiti electorate responded massively: they voted in Fayose for the second time, and voted out Fayemi for the sake of their stomachs!

What does stomach infrastructure tell us about Nigeria’s political context? In 1989, Jean-Francois Bayart, the French political scientist, popularized the expression, “politique du ventre.” The translation of this expression became the title of his book, The Politics of the Belly. The argument of this groundbreaking work is that given the patrimonial, and hence corrupt, nature of power, African politics extends the metaphor of eating and the belly into a solid framework of clientelist vertical relationships—between clients and patrons—that consumes national resources. As a twist in the tail, Bayart argues that rather than see this type of politics as negative, it is actually an effective governance model that is autochthonous to Africa. This politics, in history, is defined by the collusion of the legal and the illegal, the merger of the public and the private enterprises, the prominence of corruptive tendencies like bribery to facilitate transactions, and the private aggrandizement of public funds and resources. All this speaks to the necessities of surviving a hostile political environment; and using politics as a means to do so.

I am not sure that governor Fayose ever read Jean-Francois Bayart and The Politics of the Belly. But the practice of “stomach infrastructure” seems to point at a significant contextual reference for politics in Nigeria. Of course, we may say that Fayose was just shamefully exploiting the base existential needs of the electorate to further a political ambition. Yet, we have a responsibility to investigate the assumptions and insights behind “stomach infrastructure” to understand what it tells us about politics in Nigeria. The first significant issue for me is the relationship between existential predicament and the role of politics in ameliorating it. At what point does politics starts legitimately attending to matters of the belly? At one level, stomach infrastructure seems to shift attention away from the infrastructural deficit that is undermining real development in Nigeria, towards a more immediate and existential “infrastructure”. And this would be a justified shift because it bothers on the survival of a people outside of the capacity of the government to ensure it. And this makes it possible for greedy politicians to weigh in with palliatives that are just temporary and are not even infrastructural at all. At that level, the electorate actually mortgage four years of their right to hold the government up to good governance.

But beyond the flagrant exploitation of the poverty of the people, is there a way by which “stomach infrastructure” enunciates an emerging political culture in Nigeria? “Political culture” is a politically neutral term that could be investigated to determine what it bodes for any specific political context in terms of its capacity to define a people’s attitude and beliefs that makes a political process more meaningful for them. What does “stomach infrastructure” tell us about our preferences and the nature of our politics and political system? If we look carefully, we will notice that what we call politics in Nigeria has turned towards the base satisfaction of people’s needs. Money and food items have become the inducement to disrupt the electorate’s voting preferences. And with rampant poverty in Nigeria, it does not take serious reflection to see how people can be swayed to vote against their conscience with a mere thousands of naira and a bag of rice. Would you really blame a poor single mother who has to contend with a family of six? Would you blame an unemployed youth who has to contend with a bleak future and a host of other tensions and pressures?

It would be definitely wrong if this were to be called Nigeria’s political culture. For one, it undermines the very essence of democracy and democratic governance and its genuine concern about the infrastructural development that empowers the people. Despite the different and often conflicting ideological labels that compete for political power in the public sphere of any state, there is always the concern for the well-being of the citizens at the core of their ideological manifesto. Thus, the difference between the Tories and Labour in the UK, and the between the Republicans and the Democrats in the United States is only on the ways by which the British and the American people can be made better in well-being. It is to this extent that Nigeria requires a political culture that weighs in on behalf of the people, and defines a political template of behavior that leads to a better perspective about Nigerians as humans who depend on their politicians and leadership to make empowering policy decisions on their behalf, rather than exploiting their existential challenges for political ascendancy.

Unfortunately, there are no ideological party distinctions in Nigeria, and this is precisely where the ideological possibilities of stomach infrastructure break down completely. Outside of a virile ideological and party discourse and debate to clarify the political implications of policy decisions on the lives and welfare of the Nigerian electorate, then stomach infrastructure is taken out of its fundamental essence as the core of political concern, and left to be exploited by smart politicians with some understanding of the fickleness of populism. But I wager that if we need a really significant unfolding of a political culture in Nigeria, the idea of stomach infrastructure is as best an ideological place to start as any. This is because it points at something that stands at the core of all and any political aspirations—the well-being of those on whose behalf we seek political offices and positions. At this ideological level, stomach infrastructure goes beyond the selfish inducement of Nigerians to becoming a serious template for a deep institutional reform of our policy intelligence in a way that makes it fit to backstop our democratic experiment as a state. Stomach infrastructure references populism as a significant ideological stance. And there is nothing wrong with populism if it takes Nigeria and Nigerian seriously.

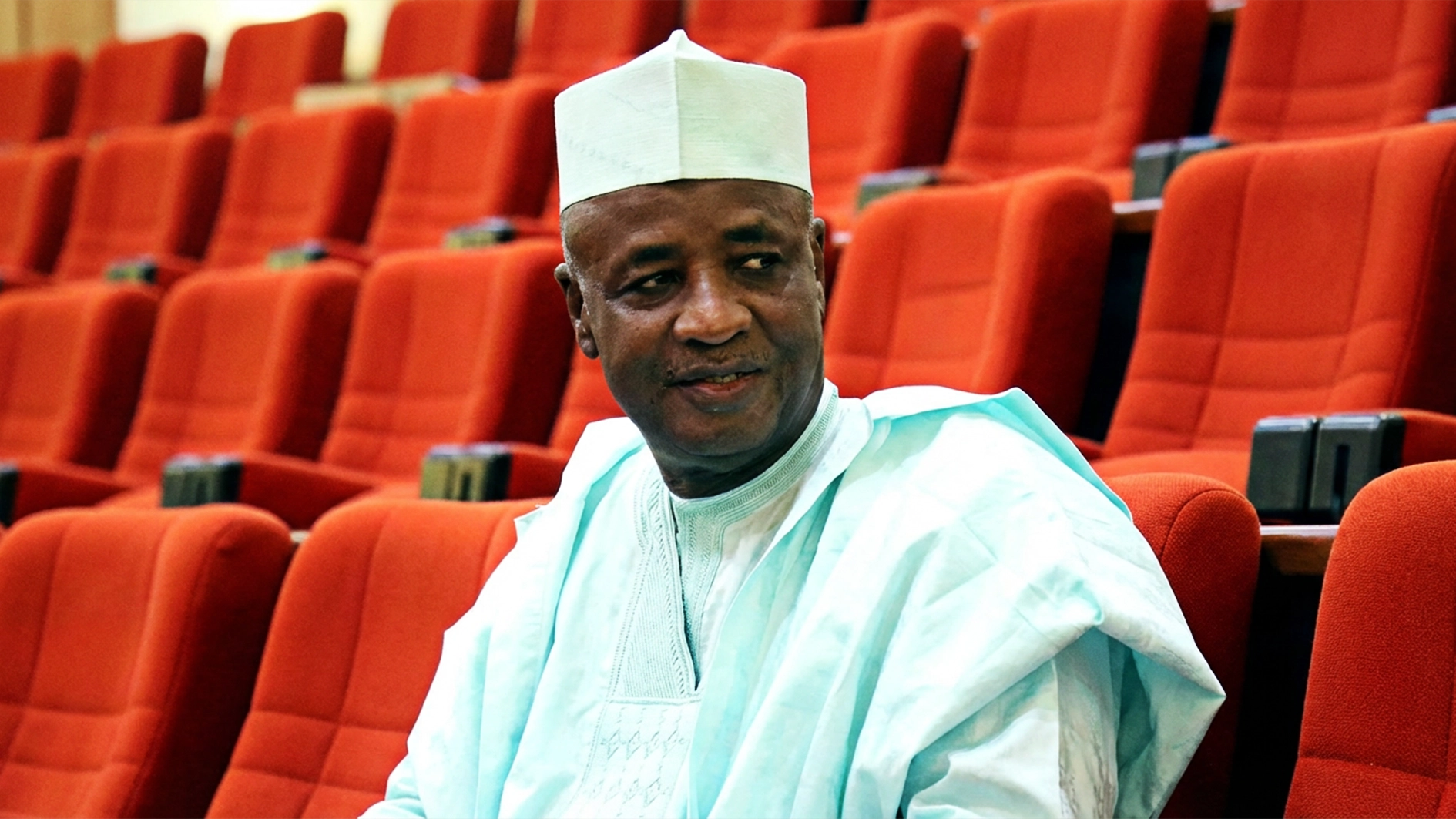

Olaopa is Executive Vice-Chairman

Ibadan School of Government and Public

Policy (ISGPP), Ibadan

[email protected]

[email protected]