By the roadside on Otitio Road in Yenagoa, Bayelsa state, smoke hung thick in the air on December 18 as Ebi Wonodi fried ‘akara’ (bean cake) on a firewood stove. Sweat streaked her face and tears welled as smoke stung her eyes.

Bayelsa is one of Nigeria’s gas-producing states, yet for Wonodi, liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) is a luxury in the coastal state, like others in a country with over 210 trillion cubic feet of gas, according to the Nigerian Upstream Petroleum Regulatory Commission (NUPRC).

“The price of cooking gas has risen beyond my reach,” she said, pausing to fan the flames. “To meet demand, I need a bigger cylinder and a high-intensity burner. The cost of the cylinder, burner and refills is more than my working capital.”

Her experience reflects a growing paradox across Africa. Despite boasting of an estimated 620–800 Tcf gas reserves, according to the African Petroleum Producers Association, millions of households and small businesses are priced out of clean cooking fuels. As costs rise, households such as that of Ugochukwu Amarachi’s in Dawaki, Abuja, and millions like hers, are returning to forests for survival. The result is a cycle of energy poverty, health risks and accelerating deforestation.

Health concerns, however, have kept Powei Obiere, a food vendor in Yenagoa, committed to LPG. She said she deliberately stretches her expenses to stay on gas because it saves time and reduces health risks. She added that firewood is not significantly cheaper once fuel quality, cooking speed and health impacts are considered.

Gas abundance, unaffordable access

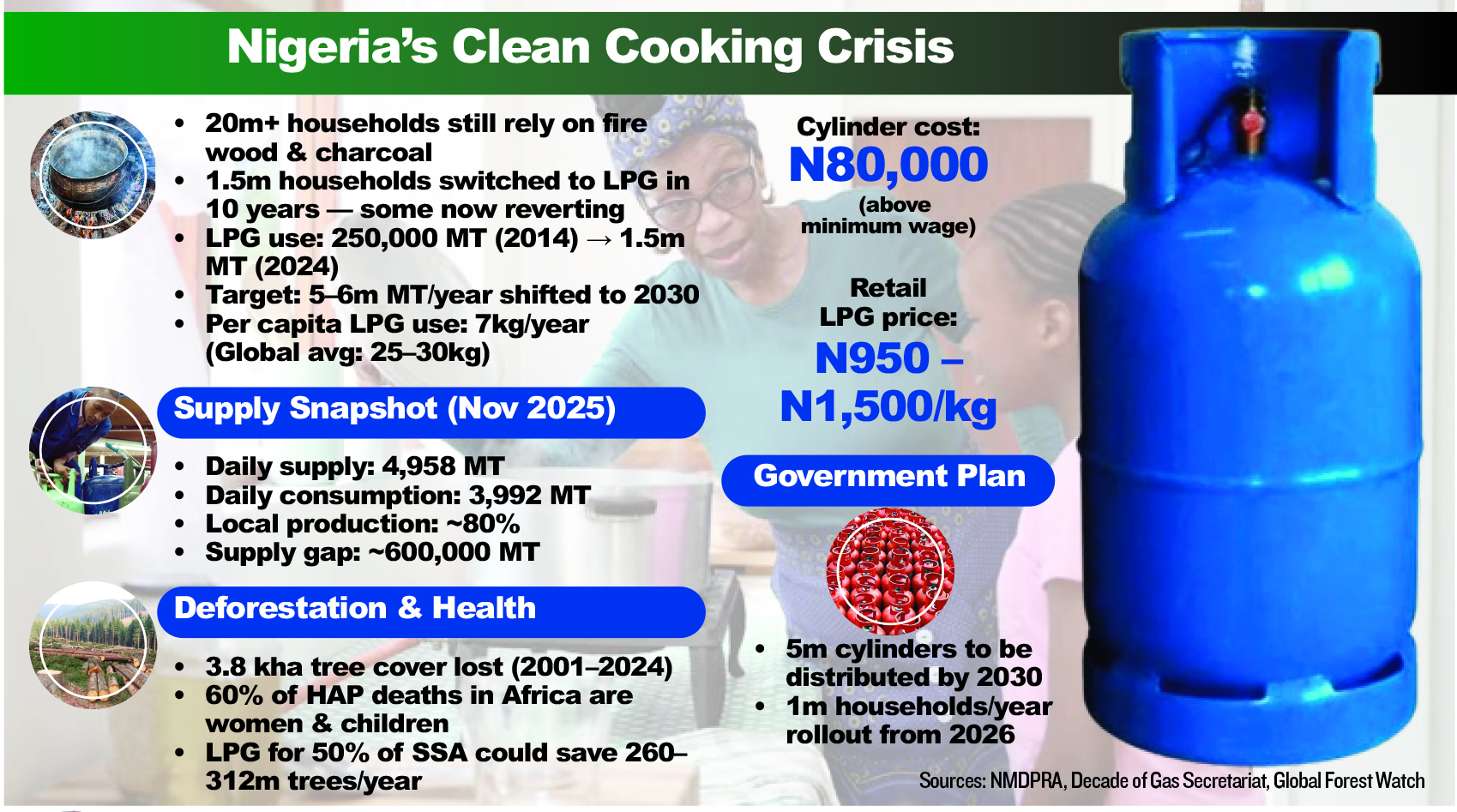

When Wonodi started selling akara in 2022, LPG averaged N816/kg. By November 2025, prices had climbed to N1,500/kg, according to the Nigerian Midstream and Downstream Petroleum Regulatory Authority (NMDPRA). Cylinder prices have also risen faster. A standard 12.5kg cylinder now costs about N48,000, placing it beyond the reach of low-income households.

As prices surged, many Nigerians reverted to firewood and charcoal, undermining Nigeria’s ‘Decade of Gas’ strategy, which promotes LPG as a transition fuel to curb deforestation and household air pollution.

Across sub-Saharan Africa, over 80 per cent of the population still relies on traditional biomass for cooking. Outside North Africa, per capita LPG consumption remains low, constrained by high upfront costs, weak infrastructure, regulatory uncertainty and limited fiscal space for subsidies.

Forests as fuel, livelihoods

In Iludun Oro, Kwara state, the forests reflect this shift. Biola Ayangbade, a graduate of the Kwara State College of Education, earns a living producing charcoal from largely unregulated logging. Each month, he fells 10 to 20 medium-sized trees, producing about 25 bags of charcoal sold for N10,000 to N13,000 each.

“Charcoal is what keeps us going,” Ayangbade said. “There are few jobs here. Many youths depend on it.” The trade is reinforced by migrant farmers such as Tarwase Torngu from Benue state, who combine farming with charcoal production. Trees cleared for cultivation are converted into charcoal, embedding deforestation in the local economy. As LPG becomes less affordable, demand for biomass rises, turning forests into both fuel and income.

Africa’s forests are central to food security, livelihoods and climate resilience. They cover about 23 per cent of the continent, roughly 674 million hectares, comparable in size to the Amazon rainforest. Yet Africa has the world’s highest rate of forest loss.

The UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) estimates that Africa loses about 3.9 million hectares of forest yearly. Nigeria alone lost about 250,000 hectares of natural forest in 2024, equivalent to 110 million tonnes of CO₂ emissions, according to Global Forest Watch (GFW). Between 2001 and 2024, Nigeria lost 1.4 million hectares of tree cover, emitting an estimated 800 million tonnes of CO₂ equivalent.GFW attributes forest loss to agricultural, logging and unsustainable fuelwood harvesting.

Women pay the highest price

Energy poverty is not gender-neutral. Women and girls bear the greatest burden. The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that women and girls in sub-Saharan Africa spend about 40 billion hours each year collecting firewood and biomass, time lost to education, paid work and rest.

“They are also the most exposed to household air pollution,” said Chief Advocacy Officer for Sub-Saharan Africa at the World Liquid Gas Association (WLGA), Michael Kelly, “because they are the ones cooking.”

LPG is viewed as the most practical near-term alternative to biomass. It is cleaner than charcoal, more efficient than firewood and significantly reduces indoor air pollution. Yet LPG penetration across Africa remains below 20 per cent.

Kelly noted that Africa consumes about 3.5 million tonnes of LPG yearly, compared with roughly 200 million tonnes consumed each year by the United States, China, India, Japan and Europe combined.

“The Lancet’s 2018 study estimates the economic cost of household air pollution-related diseases in Africa at about $120 billion per year,” he said. “Indoor air pollution kills more people than malaria, HIV and tuberculosis combined.”Smoke from solid fuels contributes to one million premature deaths yearly in Africa, he added. Women and girls bear the heaviest burden, with implications for education and school attendance.

Structural weaknesses in LPG supply

Nigeria’s LPG supply chain remains volatile. Daily supply fluctuates between 3,400 and 5,000 metric tonnes. Domestic production averages 3,200 to 4,500 tonnes per day, a significant achievement, thanks to Dangote Refinery and NLNG.

Despite more than $500 million in private investment over the past decade, the Managing Director of Rainoil Gas Limited, Emmanuel Omuojine, said affordability remains the main challenge. Annual LPG consumption has risen from about 250,000 tonnes in 2014 to 1.5 million tonnes in 2024. Nigeria now supplies about 80 per cent of its LPG locally, yet per capita consumption is just 7kg per year, far below the global average of 25–30kg.

“The increase in cost has left over 20 million households reliant on firewood and charcoal,” he said. In South Africa, PayGas co-founder, Philippe Hoeblich, argued that the traditional cylinder recirculation model is part of the problem. “To serve one customer, three to four cylinders are needed in permanent rotation. This cost forces households to buy a full cylinder each time, preventing billions of low-income people from accessing affordable cooking energy.”

South Africa’s regulations allow safe partial refilling of cylinders. “With flexible refilling, people can start cooking with as little as $0.50 worth of gas, without subsidies,” Hoeblich said, describing it as a pathway to curb deforestation linked to cooking fuel demand.

Policy promises and persistent gaps

The G20 elevated clean cooking to a global priority, adopting a Voluntary Infrastructure Investment Action Plan to accelerate clean cooking solutions. Championed under South Africa’s 2025 G20 Presidency, the initiative frames universal access as a human right and a pillar of climate action, public health and energy justice.

While politically significant, the commitments highlight how far implementation still lags. For millions of households in rural and peri-urban Africa, last-mile access, affordable cylinders, flexible payment models, safe distribution and reliable supply remain the solution.

Nigeria has pledged to expand LPG consumption from 500,000 tonnes to five million tonnes per year, initially by 2025 and now shifted to 2030. With current consumption at about 1.4 million tonnes, stakeholders warn the target will remain elusive.

Managing Director of Selai Gas, Damilola Owolabi-Osinusi, said cylinder affordability is the biggest barrier. “You cannot use LPG without a cylinder,” she said.

President, Nigerian Association of Liquefied Petroleum Gas Marketers, Oladapo Olatunbosun, said awareness is no longer the issue. “The problem is affordability,” he said, calling for targeted subsidies similar to those in India, Morocco and Niger.

Partner at Kreston Pedabo, Olufemi Idowu, warned that leaving LPG pricing entirely to market forces excludes the poorest households. He called for integrated strategies combining subsidies, micro-distribution networks, safety enforcement and public education.

A narrowing window

Experts from the IEA, WLGA, Africa Finance Corporation and Standard Bank warned that Africa’s LPG penetration will not rise without regulatory certainty, infrastructure investment and innovative financing. At an LPG Forum in Lusaka, Zambia, earlier this year, delegates cautioned that inaction risks locking millions into biomass dependence for decades.

Executive Secretary of the African Refiners and Distributors Association (ARDA), Anibor Kragha, reaffirmed a continental ambition to raise LPG penetration to 60 per cent by 2030. Achieving it, he said, will require harmonised regulations, market aggregation and regional cooperation under the African Continental Free Trade Area.