A fierce statement against abuse of power in Nigeria’s ivory towers echoed through the Senate chamber on Wednesday as lawmakers approved landmark legislation prescribing up to 14 years in prison for lecturers who sexually harass students.

The passage of the Sexual Harassment of Students (Prevention and Prohibition) Bill, 2025, marked a watershed moment in the fight against sexual exploitation in tertiary institutions — a problem long whispered about in corridors of power but rarely confronted head-on.

Moved by Senate Leader Opeyemi Bamidele (APC, Ekiti Central), the bill seeks to dismantle what he described as a “culture of coercion and silence” that has eroded trust between educators and students.

Bamidele said the legislation was crafted to “protect students from all forms of sexual misconduct and abuse within academic environments”, while enshrining respect for human dignity and ethical standards in teaching.

“This law safeguards the sanctity of the student-educator relationship built on authority, dependency and trust,” he told his colleagues. “It ensures that no educator ever uses that trust as a weapon of exploitation again.”

Under the new Act, educators convicted of sexual harassment face a minimum of five years and up to 14 years’ imprisonment, with no option of fine.

Lesser but related offences attract between two and five years’ imprisonment, also without a fine.

The law lists as offences: demanding or forcing sex from a student or prospective student; making unwelcome sexual advances or creating a hostile environment; touching, kissing, hugging, or pinching a student in a sexual manner; sending sexually explicit pictures or remarks; stalking or making sexually suggestive jokes or comments.

Even indirect complicity, such as aiding or inducing another person to commit sexual harassment, now carries criminal weight.

The Act also removes the defence of consent, stating clearly that “it shall not be a defence that a student consented” to the act. Only a legally recognised marriage between both parties may serve as an exception.

Students or their representatives — including family members, guardians, or lawyers — can now file a written sexual harassment petition directly with the Nigerian Police Force, the Attorney-General, or the institution’s Independent Sexual Harassment Prohibition Committee.

Every tertiary institution will be mandated to establish such a committee, empowered to investigate and deliver final decisions on complaints in line with the law.

However, once a case enters court, no internal disciplinary panel may continue the same matter to avoid conflicts of jurisdiction.

The passage was not without debate. Senator Adams Oshiomhole (APC, Edo North) praised the intent but argued the law should cover harassment in workplaces and public institutions as well.

“There is no need to restrict this law to students,” he said. “Sexual harassment exists everywhere — in offices, factories, and even politics. We should give this bill universal application.”

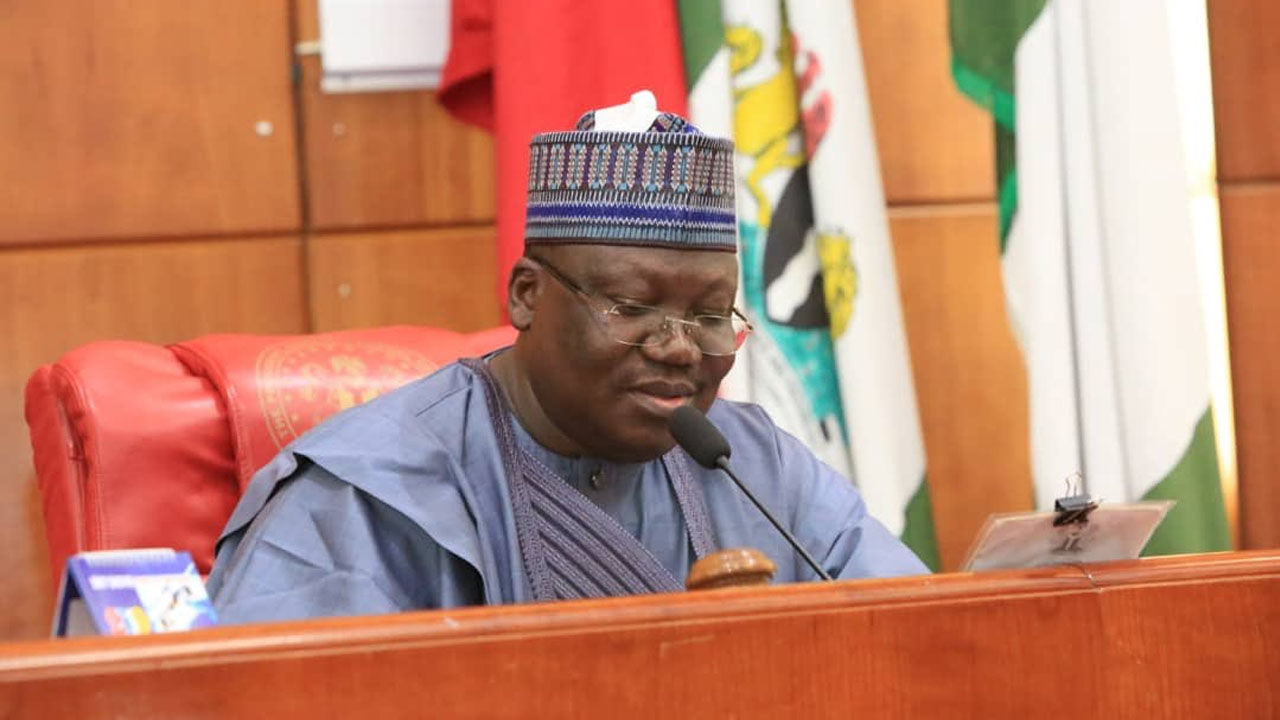

Deputy Senate President Barau Jibrin (APC, Kano North), who presided, explained that because the legislation came from the House for concurrence, major amendments were not permissible.

He added that existing laws already govern harassment in workplaces, stressing that this Act focuses solely on the education sector, where cases have become alarmingly common.

For years, Nigerian campuses have been rocked by stories of “sex-for-grades” scandals, many of which went unpunished. The Senate’s decision, analysts say, signals a zero-tolerance era for such abuses.

The bill’s passage represents not only a legal victory but also a cultural one — a push to reclaim higher education as a place of mentorship, not manipulation.

“This law gives voice to the voiceless,” one female lawmaker said after the vote. “No student should ever have to trade dignity for a degree.”

With the concurrence vote sealed, the bill now awaits presidential assent to become law — a move expected to set a new moral benchmark for Nigerian tertiary education.