Once upon a warm, windy morning, I was a successful young medical doctor in the sprawling metropolis of Lagos City. Seated at the back of my sleek sedan, on my way to an official meeting, I casually asked the driver to stop. Obediently, he parked by the side of the bustling Third Mainland Bridge. Before getting down, I pushed a handwritten note underneath my office bag. Then, walking away from the car, I placed my hands on the balustrades overlooking the vast Lagos Lagoon. Looking through his side mirror, the driver thought I was stabilising myself against the whooshing winds. Then, instead of peeing like I had said, I lifted one leg over the sides of the bridge, then the other, and let myself drop.

A distant scream, mine or someone else’s? It didn’t matter. One loud whooshing sound, and then another. The din of cars passing on the bridge above me, then the whoosh of the cold wind as I sliced through the air like a heavy knife, were a perfectly fitting soundtrack to this dramatic curtain call.

In that long moment, as the world blurred in slow motion, I could smell the stench of the water, as a mix of dead fish, seaweed and a whiff of brine engulfed my senses. I was still falling. Then another whooshing gust of wind brushed against my face. The wind was strong, and my shirt collar flapped against my ear as the ocean’s wall rose to welcome me. Whooshing sounds soon became a deafening all round cacophony, a rising crescendo of surging waves and thoughts and memories that flashed before me in that final moment. I felt panic. I felt regret. I felt anger. I felt peace.

Soon we were face to face, and I heard one long whooooosh, then a muted splash, then utter silence. This first contact was the intimate, long kiss of absolute union. Like a mother to her child, the extensive surface of the lagoon welcomed me with open arms, and a wide grin as wide as the ends of the earth. Water smashed against my fragile body, and I smashed against water, until I tasted blood in my mouth and felt water and water felt me, and I could feel no more.

The news spread quickly, of a successful young doctor’s shocking suicide. In one photo, the woman at the centre of it all stood by the bridge and stared into the distance. A dear mother, whose grief will be complicated by the tarnishing of the social prestige accruable from having a doctor as a child!

Really, I should know how it feels. Once, I failed an exam in medical school. I had never failed before. On the contrary, I had been a star all my life. In those days, I began to sleep in the fetal position long before I knew what that meant. One lonely afternoon, as I lay in bed, I imagined a knife on my wrist, then a noose around my neck; but I was afraid of the pain, so instead, I burst into tears and ran out. I ran into the arms of my mother, who held me to her bosom and promised me I wouldn’t die.

Thus went my closest shave with what was colloquially known as a ‘mental breakdown’. Not so lucky for these two handsome boys that lived around our street in New Bodija. Their father was a well-known retired judge. Every day, these identical twins would walk down the streets in their shorts, stop around the newspaper vendor, smoke some pot, and walk back home. People said they used to be ‘abroad’ but they were ‘called home.’ The calling home was via ‘remote control’, and the people responsible were called “àwon ayé”: malicious spiritual forces unleashed by an angry old relative or a stepmother in ‘the village.’ Everyday when we were being driven to school, I would peer at the scruffy twins through the car windows, wondering who was ‘doing’ them, and thinking how terrible it must be to ‘run mad’.

So, what does a ‘mad person’ look like? Stereotypically, he or she would be butt-naked roaming the streets, or jaywalking in torn rags picking rubbish out of trash bins. The Yoruba have a word for this, “wèrè aláso”, literally crazy person who is well-composed and still clothed. Indeed, the image of mad people with dirty dreadlocked hair known as ‘dada’, who mutter to themselves while punching the air and fighting invisible enemies, has become a staple of indigenous movies. Commonly, overly dramatic actors ‘run mad’ as a result of bad karma after committing a crime, or due to wicked spiritual forces, who turn out to be their family members or friends.

Shame, and the stigmatisation of psychiatric conditions also fuel deliverance ministries, which compete with psychiatric hospitals for relevance in the psyche of the average Nigerian. That is why the word ‘asylum’ in Europe means a process for refugees, but in Nigeria, it connotes a home for the mentally ill. There are several of these specialised psychiatric institutions: from the most famous, Aro Neuropsychiatric Hospital in Abeokuta, to Lantoro, to several Federal Neuropsychiatric Hospitals such as “Yaba Left”, euphemistically named for its position on the left of the one-way that runs parallel to Yaba market, and the psychiatric ward in LUTH, Lagos or the Adeoye Lambo Ward in Ibadan’s University College Hospital, which is named after a one-time Deputy Director General of the World Health Organisation, himself a world renowned psychiatrist.

Yet, the success of these mental healthcare institutions depends on social perceptions, shame and stigma. In fact, we need to kick-start a conversation about the outsized role of shame and stigma in the socialisation of Nigerians. Why, for example, are most Nigerians adept at weaponising words during interpersonal conflicts? For instance, I can find 20 different ways to say ‘you are mad!’ in Nigerian languages. Meant to be half-jocular, these saucy invectives make use of superior wordplay to belittle an opponent during an altercation; but their abundance suggests an important fact: that shaming and stigmatisation of mental health issues is culturally embedded in Nigeria.

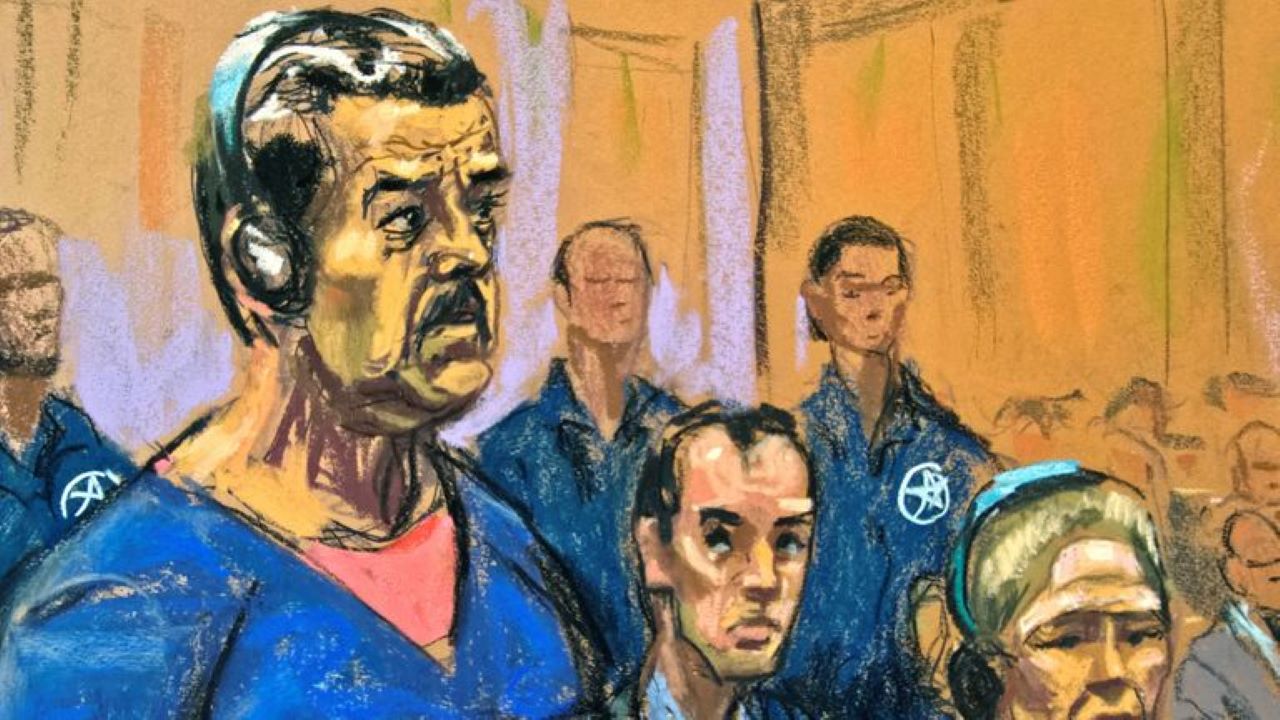

Which is why the surprising suicide of Dr. Allwell Orji rightly sparked a social media conversation about attitudes to mental health in Nigeria. If you consider for a moment that, one in four people worldwide have a mental disorder, chances are you already have a friend or family member living with mental illness right now – and you don’t even know. Worse, he or she might not know either. So, when next you are tempted to shout “Ndí arà!” or “Olóríburúkú”, will you consider that you might just be stigmatising someone who is struggling with mental health issues?

Dr. Adene is a public health specialist based in The Netherlands.