•Study blames surge in type 1 diabetes mellitus among Nigerian children on COVID-19 pandemic

•Study blames surge in type 1 diabetes mellitus among Nigerian children on COVID-19 pandemic

•More than 150,000 diabetics in UK to get N6m ‘artificial pancreas’ gadget

•Researchers step closer to injection-free diabetes care, innovation in insulin-producing cells

Scientists have recorded breakthroughs in the treatment of type 1 diabetes, even as a study published in the Annals of Ibadan Postgraduate Medicine journal associated the surge in type 1 diabetes among Nigerian children with COVID-19 pandemic.

According to the researchers, a substantial increase in Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus (T1DM) has been reported globally among children following the discovery of COVID-19.

Meanwhile, the British National Health Service (NHS) regulators on Tuesday, said more than 150,000 adults and children with type 1 diabetes in United Kingdom (UK) are now eligible to get an “artificial pancreas”.

Experts say the approved hybrid closed-loop system technology is the “biggest breakthrough since insulin.” The technology – which costs less than £5,000 (N6 million) per patient – uses a ‘hybrid closed-loop system’ sensor to continually monitor blood glucose.

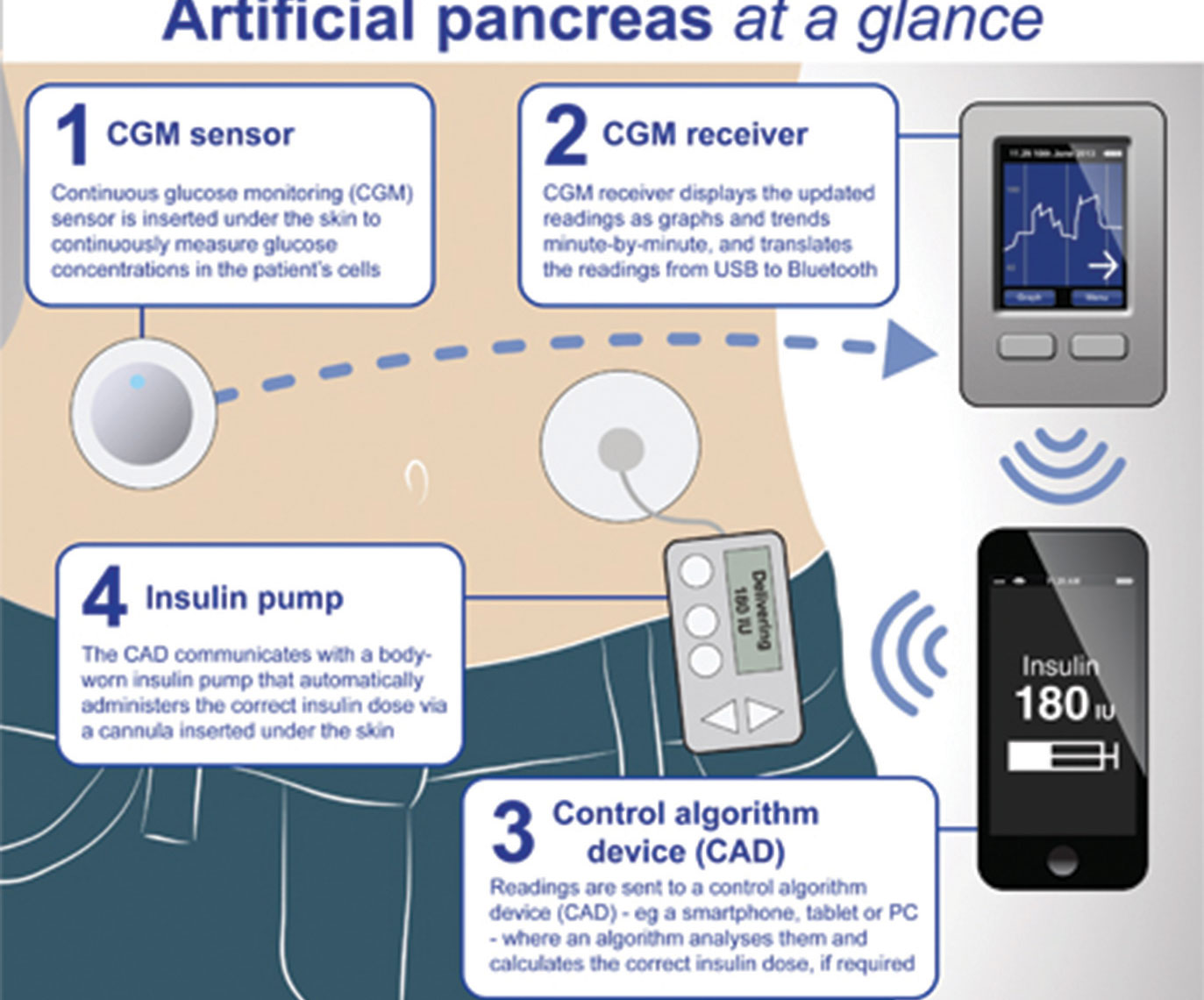

According to a report first published in Daily Mail UK, the high-tech device continuously tracks blood sugar levels through a sensor stuck to the body. Readings are fed straight back to a body-worn insulin pump, with an algorithm then calculating how much of the hormone needs to be released.

National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) chiefs recommend people in England and Wales can get a hybrid closed loop system if their type 1 diabetes is not adequately controlled.

NICE is tasked with providing guidance on current best practice in health and social care, including public health, to the NHS in England and Wales.

Nearly 300,000 people in England and Wales are estimated to have the autoimmune condition. This includes thousands of children. It occurs when the body stops making enough insulin to regulate blood sugar levels.

Sufferers typically have to regularly measure blood glucose levels using finger-prick blood tests. Some already use a continuous glucose monitor, allowing them to manage their own levels with multiple daily insulin injections.

How will the ‘artificial pancreas’ work? The sensor wirelessly transmits readings to the high-tech insulin pump, which runs a mathematical calculation to work out how much insulin needs to be delivered at a time into the body to keep blood glucose levels within a healthy range.

The body worn insulin pump then automatically delivers insulin into the bloodstream.

This can be particularly challenging for children given the variations in the levels of insulin required and the unpredictability that surrounds how much youngsters eat and exercise.

They are at higher risk of dangerously low blood sugar levels (hypoglycaemia) and high ones (hyperglycaemia), which can cause damage and even prove fatal.

All children and young people, women who are pregnant or planning a pregnancy, and sufferers who already have an insulin pump will be first to be offered the gadget as part of a five-year roll-out plan.

Chief Medical Officer at NICE, Prof. Jonathan Benger, said: “With around 10 per cent of the entire NHS budget being spent on diabetes, it is important for NICE to focus on what matters most by ensuring the best value for money technologies are available to healthcare professionals and patients.

“Using hybrid closed loop systems will be a game changer for people with type 1 diabetes.

“By ensuring their blood glucose levels are within the recommended range, people are less likely to have complications such as disabling hypoglycaemia, strokes and heart attacks, which lead to costly NHS care.

“This technology will improve the health and wellbeing of patients, and save the NHS money in the long term.”

Chief Executive of Diabetes UK, Colette Marshall, said the new technology “has the potential to transform the lives of many people with type 1 diabetes, improving both health and quality of life.”

She said: “We’re excited to welcome these recommendations which broaden access to the technology for key groups including children and young people, recognising our comments to the consultation earlier this year.

“However, funding to roll out this technology to the people that need it is of paramount importance and we reiterate the campaign call we made last month for the Government and the NHS to agree to this.

“We’ll also be working with the NHS to help ensure that everyone who could benefit from this technology has access to it as soon as possible in the phased rollout that has been agreed to achieve this.”

National Specialty Adviser for Diabetes, Dr. Partha Kar, said: “This is amazing news for people living with type 1 diabetes and this announcement can be made possible thanks to the hard work of the NHS, once again trialling and testing the best and latest innovations for the benefit of our patients.

“This tech might sound sci-fi like but it will have a dramatic impact on the quality of people’s lives, not to mention outcomes – it is as close to the holy grail of a fully automated system as science can provide at the moment, where people with type 1 diabetes can get on with their lives without worrying about glucose levels or medication.”

The Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (JDRF) called it “the biggest treatment breakthrough for type 1 diabetes since the discovery of insulin.”

Meanwhile, a team has developed a new step to improve the process for creating insulin-producing pancreatic cells from a patient’s own stem cells, bringing the prospect of injection-free treatment closer for people with diabetes.

A University of Alberta team has developed a new step to improve the process for creating insulin-producing pancreatic cells from a patient’s own stem cells, bringing the prospect of injection-free treatment closer for people with diabetes.

The researchers take stem cells from a single patient’s blood and chemically wind them back in time, then forward again in a process called “directed differentiation,” to eventually become insulin-producing cells.

In research published this month, the team treated pancreatic progenitor cells with an anti-tumour drug known as AKT/P70 inhibitor AT7867. They report the method produced the desired cells at a rate of 90 per cent, compared with previous methods that produced just 60 per cent target cells. The new cells were less likely to produce unwanted cysts and led to insulin injection-free glucose control in half the time when transplanted into mice. The team believes its efforts will soon be able to eliminate the final five to 10 per cent of cells that do not result in pancreatic cells.

Canada Research Chair in Transplant Surgery and Regenerative Medicine and head of the Edmonton Protocol, which has allowed 750 transplantations of donated islet cells since it was first developed 21 years ago, James Shapiro, said: “We need a stem cell solution that provides a potentially limitless source of cells. We need a way to make those cells so that they can’t be seen and recognized as foreign by the body’s immune system.”

The researchers suggest this safer and more reliable way to grow insulin-producing cells from a patient’s own blood could eventually allow transplants without the need for anti-rejection drugs. Recipients of donated cells must take anti-rejection drugs for life, and the therapy is limited by the small number of donated organs available.

Shapiro says further safety and efficacy studies will need to be carried out before transplantation of stem-cell-derived islet cells is ready for human trials, but he is excited by the progress.

Meanwhile, the twelve-year retrospective review of all cases of T1DM among children that presented in Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital (NAUTH) Nnewi, Anambra State, South-East Nigeria from January 2010 to November 2021, Annals of Ibadan Postgraduate Medicine journal, concluded: “This study adds to the growing body of evidence indicative of a possible link between COVID-19 and T1DM among adolescents. There is an imperative need for multi-centre studies to further establish the evolution of this disease and its probable link with COVID-19. In the interim, we advocate for a revision of the existing national COVID-19 clinical practising guidelines to incorporate cases of pre-existing diseases suspected to be linked to the virus for free viral testing, which can only improve the veracity of published works emanating from the resource-constrained region.”

Initially, anecdotal evidence attributed this alarming link between T1DM and COVID-19 to a variety of factors, including the effect of pandemic-induced stress on the chronic release of counter-regulatory hormones, late presentation of cases, and delayed diagnosis due to inadequate insurance and out-of-pocket payment. However, the recent discovery of elevated angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptors (the primary binding site for COVID-19) in pancreatic tissue substantiated the hypothesis of extensive damage to pancreatic beta cells exacerbating the risk of early-onset T1DM, particularly in genetically susceptible individuals. Additionally, since children are generally exempt from receiving the COVID-19 vaccine due to the negligible risk of developing severe disease, this may provide another plausible explanation for the increasing prevalence of COVID-19-related late-onset co-morbidities, including T1DM.

Also, another study published in Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism (JPEM) examined clinical characteristics and compliance with care of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus in Nigeria.

The study also confirmed that the prevalence of T1DM is increasing in most developed and developing countries and described the clinical characteristics and compliance with care among Nigerian children and adolescents with T1DM.

They concluded: “The compliance of children with dietary recommendations and insulin therapy was poor. Efforts should be strengthened at all healthcare facilities to educate parents on the need for compliance with management guidelines.”

The researchers are from Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Lagos State University College of Medicine, Ikeja, Lagos; Department of Paediatrics, Aminu Kano University Teaching Hospital, Kano; Department of Paediatrics, Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospital, Ile-Ife; Department of Paediatrics, Babcock University Teaching Hospital, Ilishan-Remo; Department of Paediatrics, College of Medicine, University of Lagos, Akoka, Lagos; Department of Paediatrics, College of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Ibadan; Department of Paediatrics, Murtala Muhammed Specialist Hospital, Kano; and Departments of Paediatrics, Obafemi Awolowo College of Health Sciences, Olabisi Onabanjo University, Sagamu, Ogun State.

Nigeria is one of the 48 countries of the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) African region. According to the latest figures from the IDF, 537 million people have diabetes in the world and 24 million people in the African Region; by 2045 it will be around 55 million.

A breakdown of Diabetes in Nigeria (2021) showed 96,812,400 of the total adult population with 3.7 per cent prevalence and there are about 3,623,500 total cases of diabetes in adults.

T1DM was known as insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM), while Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) has been known as non-insulin-dependent diabetes (NIDDM).