How the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) responds to the growing call for monetary policy neutrality (or easing in its extreme form) this year, starting this week’s opening meeting, will determine where the past 15-month interest rate takes the economy, GEOFF IYATSE writes.

How the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) responds to the growing call for monetary policy neutrality (or easing in its extreme form) this year, starting this week’s opening meeting, will determine where the past 15-month interest rate takes the economy, GEOFF IYATSE writes.

Monetary policy decisions, like other economic choices, are not a walk in the park. They are tough decision-making processes not only because they are taken based on outcomes of models built on simplified assumptions but also because they require that an economy sacrifices some gains to enjoy some benefits.

Perhaps, economics as a dismal science derives much of its modern relevance from the complicity of monetary policy choices. For one, the twin challenges the global community has had to battle with since the turn of the 21st century – unemployment and fragile growth – are mutually exclusive. Notwithstanding the country’s desire to bring down the unemployment level to what economists call the steady state (place of rest or natural level) and achieve fast growth, it is the job of monetary policymakers to exchange one for what they consider more demanding.

It is, indeed, not any different from choosing to embrace the devil or dive into the deep Red Sea. This week, the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC), the rate-fixing (another simplification of an extremely complex responsibility) arm of the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) is at that crucible again, perhaps staring at the jaw of a shark and the claws of a tiger.

But really, the MPC has more headroom in the not-too-slow growth seen last year. While the economy declined from 3.46 per cent in the fourth quarter (Q4) of 2023 to 2.98 per cent in last year’s first quarter (Q1), the upward slope seen through 2024 has been promising. By the third quarter, the growth reclaimed its Q4’23 momentum and it is projected to finish the year at 3.6 per cent. Except it is decoupled into its sectoral variations, a nearly 3.5 per cent yearly growth, as some economists have projected, is not weak. This is a comfort level for advocates of pro-restrictive monetary policy.

The growth momentum of the past two years also detracts from the significance of model building and exposes the underbelly of the structure of Nigeria’s economy. Where on earth does an economy grappling with an above 20 per cent policy rate pull three per cent growth? There are rough rationalisations for this, including the larger-than-life informal component of the economy. But this reason does not fully explain how the financial sector achieved 32 per cent growth in the third quarter (Q3) of last year whereas agriculture, a largely informal and less interest rate-sensitive sector, grew by a mere 1.14 per cent.

As expected, manufacturing posted 0.92 per cent, showing the true weight of the interest rate pass-through effect and signalling the danger of continual tightening. There are reasons to be worried about manufacturing’s snail growth. First, it is the bastion of the country’s economic competitiveness and terms of trade position. And for the contribution of such an important sector to the total output to drop from about 15 per cent to less than nine per cent in about three years (coinciding with the period of aggressive tightening), there are sufficient reasons to be worried.

Gains of restrictive monetary policy

It is not, thus, surprising that advocates of robust local manufacturing have taken the lead in the call for a return to neutral or loose monetary policy. In the face of declining real sector growth, as highlighted by manufacturing and agriculture, a hasty interest rate cut risks undermining the gains of the previous year’s tightening – rising capital inflow and exchange rate stability, especially.

With the resurgence of inflation rate concerns, advanced central banks are at a crossroads. Today, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), the rate-fixing arm of the United States Federal Reserve System, which had switched to a neutral policy option, has a rate hike possibility on the table. Even if it does not eventually resume tightening, the market is already pricing in the option, including rising caution on risky assets.

What does this mean for the Nigerian market? Except the interest rate remains super attractive, the country could find it difficult to attract fresh capital. In a worst-case scenario, there could be a reversal of the positive trend witnessed last year, with foreign portfolio investments (FPIs) finding other destinations as various debt instruments mature.

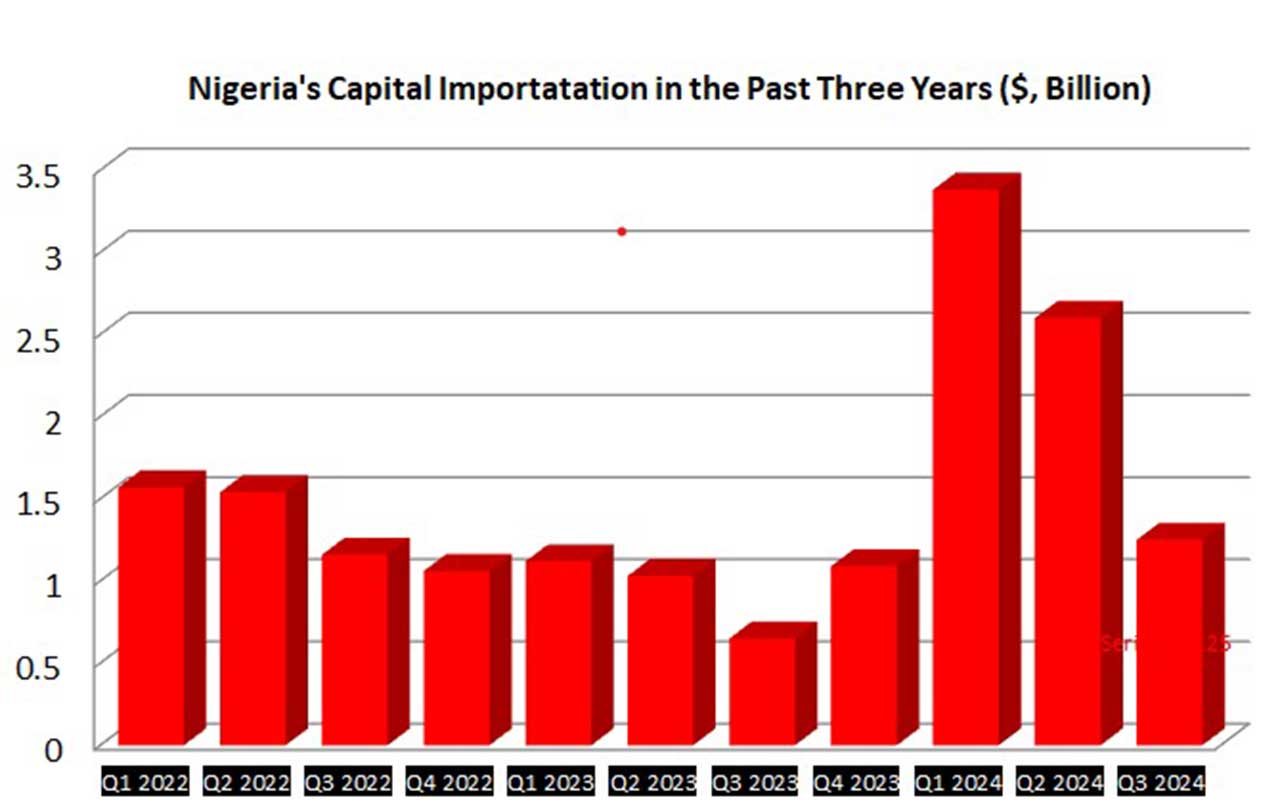

Nigeria attracted $7.2 billion in capital importation in the first nine months of last year, a 157 per cent year-on-year increase from $2.8 billion inflow in 2023. The growth rode on the recent attractive interest rates. Aligning with the objective of Yemi Cardoso’s rate hike, pressure on the naira has reduced significantly with the currency currently trading around N1510/$, an impressive appreciation from its yearly high (N1690/$).

The MPC, most likely, will prevent last year’s foreign exchange (FX) nightmare when the naira, between January 15 and the end of February lost over 40 per cent of its value only for it to gain nearly N500/$ in the subsequent 30 days. The country is still paying the price of the FX pass-through effect of the extreme volatility seen in those few months, and a revisit could be disastrous for the economy.

Eve of super liquid banks, credit bubble risk

Since November 2023 when Cardoso-led MPC first raised the interest rate (by 400 basis points), the money supply, which should be a decreasing function of the cost of borrowing, stood at N66.2 trillion. Since then, the interest rate has risen by 8.75 per cent. But so also is aggregate money supply – which has grown even faster than the interest rate – by 65 per cent to its current 108.9 trillion.

What does this imply? In a financial drought when the money supply should be restrictive, Nigeria’s money balances continue to grow putting enormous pressure on the FX market and general prices. Otherwise, money growth hits the superhighway. And this is what Nigeria may have with some banks, magically, surpassing their capital raising targets ahead of the 2026 recapitalisation deadline.

In the meantime, eight banks have raised nearly N1.6 trillion with UBA, FirstBank, Stanbic IBTC and some tier-3 operators yet to add their figures. The huge fresh capital flowing into the banks means Nigeria is on the eve of super liquid banks as witnessed in 2005/2006 again. This leaves CBN (and its important monetary regulation arm) with dual responsibilities – sustain the moderate price stability gain and build on it as well as prevent a credit bubble. To achieve these tough tasks, the authority would need a good blend of monetary and prudential tools. Certainly, an interest rate cut is not a good place for the MPC to start.

Sadly, Nigerian banks appear not the best in corporate governance practices. In many cases, funds are borrowed for plant expansion only to be converted to financial asset purchases. The country saw how fragrant disregard of credit utilisation policies triggered a bubble that almost ruined the entire banking industry and the capital market in the post-2005 consolidation and the easy money that followed – a scenario the CBN would need to prevent.

The hard choices

The trade-off choices before the MPC as it resumes this week are, at the risk of repetition, tough. The country needs faster growth, especially across the different clusters of the real economy, to create jobs, raise the standard of living of the citizenry and improve on the disappointing misery index. The government, besides the nebulous $1 trillion economy target, needs to aggressively grow the economy to raise tax revenue to bridge the wide fiscal deficit, which may widen with the expanded budget estimate to N18 trillion. These lay sufficient ground for pro-growth policy – whether monetary or fiscal.

However, the demand for more money, whether by individuals or the government, becomes illusionary if it does not increase the quantity or quality of goods and services it can buy on account of high inflation. Of course, the rising inflation rate, an outcome of deep-seated structural defects, has defied the tightening cycle setting a new multi-decade high in December.

Yet, there is a consensus that there are no fresh catalysts to push up the curve, whose intensity seems to be weakening even ahead of the planned rebasing. But in the face of the rising inflation-wary global community, rising liquidity and multi-layer domestic risk, a premature rate could refuel the dousing flames.