Enlightened societies are typically characterised by consistent adherence to the rule of law,fairness, policies which meet the proportionate, rational, and responsible objectives of health and social care advancement, educational and socio-economic development, international cooperation, law and order, defence, national interests, and security, and of course, citizens’ welfare.

The latter encompasses their protection, the right to life to liberty, right to fair hearing, transparent justice via the agency of an independent judiciary. It extends to the right to freedom of expression, association and peaceful assembly; right to the freedom of thought, conscience, and religion; and importantly, the right to private and family. However, these rights are neither absolutist nor utopian. They are circumscribed by exceptions prescribed by law.

For instance, the right to life, imposes an obligation not to take the life of another, except where permitted by law. Also, the right to freedom of assembly is limited strictly to lawful (not unlawful!) assembly. That jurisprudential anchor hooks extant proposals in Nigeria to link citizens’ unique national insurance identity data with their credit scores, potentially impeding their ability to access credit, obtain passports, driving licenses, and even rent homes.

Discourse

What is the harm which the proposal attempts to cure? Is the proposal reasonable? How much sensitisation was undertaken prior to the policy announcement? Does it command the support of the affected literate and illiterate population? Is this a surreptitious attempt to compel Nigerians to increase their credit-taking and, by extension credit risk exposure, and maximalist capitalism? Is it proportionate relative to the legitimate objective of establishing an accountable credit scoring and tracking model? What are the implications on state surveillance, privacy, and civil liberties?

As an overarching hypothesis, proposals which aim to scale financial inclusion – that is, seamless access to affordable financial services and products including, but not limited to payments, savings, credit, insurance, pensions, and capital market products; transform economic growth and sharpen financial stewardship are incontestable. In the same vein, lawful initiatives which curb loan repayment defaults, reduce fraud, mitigate financial crimes, and adhere to international best practice are in order. Not least because the country’s financial sector has been plagued by complexities including crippling interest rates, restricted access to any such credit, and opacity.

This point is affirmed in part by the 2016 McKinsey Global Institute “Digital Finance for All” (Nigeria) report. It established the potential economic benefits of digital financial services alone, as a financial inclusion sine qua non, as drawing 46 million new individuals into the formal financial system; boosting GDP growth by 12.4 per cent by 2025 ($88 billion); attracting new deposits worth $36 billion; providing new credit worth $57 billion; creating three million new jobs; reducing leakages in government’s financial management annually by $2 billion.

Besides, the revised National Financial Inclusion Strategy (2018) seeks to promote a financial system that is accessible to all Nigerian adults, at an inclusion rate of 80 per cent over the medium to longer term. Thus, the proposal offers opportunities for improved credit access for individuals and businesses; mitigate lending risk exposure for established financial institutions, thereby facilitating more empirical and scientific credit-worthiness decision making. Equally, it should enhance accountability and transparency, potentially stifling abuse and corruption.

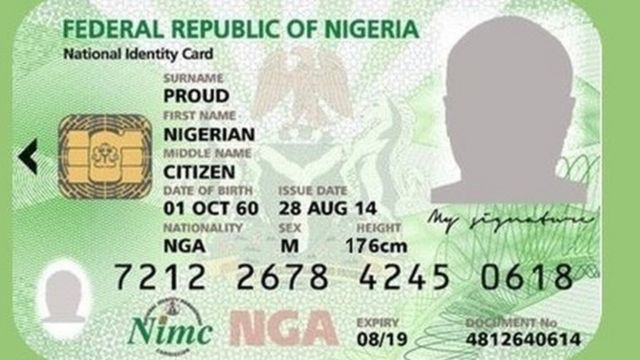

Together, these dynamics inform the government’s financial inclusion reform proposals and specifically, the extant policy of integrating the country’s National Identity Numbers (NINs) with a single credit reference agency whilst attaching onerous conditions for infractions and non-compliance with financial contracting terms with relevant parties.

Notwithstanding the intended policy objectives, the significant risk of disorder emanates from potential infringements of civil liberties, disproportionality, irrationality, constitutional overreach, and unreasonableness.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) characterises civil liberties as “the basic rights and freedoms guaranteed to individuals as protection from arbitrary actions or invasion of the state without due process of law” Civil liberties are defined in section 33, through 43 inclusive, of Chapter IV, Fundamental Rights, of the Nigerian Constitution 1999 (as amended) (the “Constitution”) to include the: right to life, right to the dignity of the human person, right to personal liberty, right to fair hearing, right to private and family life, right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion, right to freedom of expression and the press.

It includes the right to peaceful assembly and association, the right to freedom of movement, the right to freedom of discrimination, and the right to acquire and own an immoveable property anywhere in Nigeria. The inference of the right to own and acquire an immoveable property anywhere in Nigeria, inescapably implies the right to acquire a legal and an equitable interest in immovable property; which, on its explicit definition includes a lease hold and/or equitable property interest.

Accordingly, the current proposal on impeding a citizen’s right to rent a home, on account of a loan default, immediately runs counter to the provisions of section 43 thereof, on the right to acquire property in the country, and inductively, an interest in property. Clearly, this is a constitutional infraction and should not stand on the grounds of disproportionality.

Indeed, the Nigerian Supreme Court case of Lagos State v Ojukwu (1986) is a seminal judicial authority establishing the pertinence of protecting individual rights against ultra vires actions by government and supports the reasonable contention herein, that the policy aim of attempting to deny citizens the ability to rent homes, in extremis, for loan defaults is a disproportionate attempt to remedya curable defect.

Simply, a loan default is, by definition a contractual breach and should be addressed via appropriate civil remedies or, the criminal law, as the unique facts justify. How, for example, does denying a citizen the ability to own a driving licence, obtain a passport, or rent a home, for a loan default assist that person infinancial rehabilitation and financial inclusion if he/she cannot drive an Uber taxi to repay his loan, feed and house his family?!

Another mission critical risk pertains to the diminution of data privacy. As the proposal stands, a citizen would need to submit to detailed forensic know-your-customer (“KYC”) demands to a multiplicity of organisations including the banks and related financial institutions, credit reference agencies, regulatory authorities, NIBSS and others to access credit. Ordinarily, where personal data is robustly secured and safeguarded, the risk of serious data security breaches are mitigated.

However, according to The Vanguard (August 1, 2025), between 2017 and 2023, “Nigerian financial institutions, including commercial banks, fintech firms and network service providers, were reported to have suffered losses exceeding N1.1 trillion due to various cyber threats such as hacking, ransomware and malware attacks”Citizens need to be reassured as to the integrity, robustness, and security of their personal data, before forcibly integrating their NINs with credit scores.

Surveillance is yet another serious concern from the perspective of civil liberties. Currently, citizens have, or are required to have, as the context justifies, a swathe of official documents issued by a variety of regulatory and/or security agencies at federal and state levels to access services, establish rights and or otherwise prove identity.

These include 1.) The National Identity Card, issued by the National Identity Management Commission (NIMC). It contains a citizen’s unique National Identification Number (NIN); 2.) The National Electronic Identity Card, issued by NIMC; 3.) Biometric Driving Licences, issued by the Federal Road Safety Commission; 4.) Biometric National Passports, issued by the Nigerian Immigration Service; 5.) Residency Cards, issued by State Governments; 6.) National Health Insurance cards, issued by the National Health insurance Agency (NHIA); 7.)Permanent Voter’s Card, issued by the Independent National Electoral Commission(INEC).

The material risks here are threefold. First, the risk of disproportionate surveillance by regulatory authorities. Second, is the misuse of citizens’ personal data. Third, is the cost-burden on citizens having to acquire, at times, willy-nilly, all or some of these official documents. This not only imposes unnecessary bureaucratic and cost burdens on citizens, but erodes trust in state authorities and dissipates civil liberties.

Finally, the risk of abuse of power is significant. With the government’s enormous access to and oversight of citizen’s private data, this gives the state extraordinary access to sensitive personal data. Of course, governments of democratic and non-democratic complexions, in various countries have used sensitive information to target individuals, opponents, and communities for nefarious purposes.

For example, Egypt’s and Ethiopia’s, use of citizens’ data has been used to track and prosecute critics and opponents; just as India’s Aadhaar Programme has been criticised for its potential for misuse and surveillance.

Conclusion and recommendations

Whilst financial inclusion and policies aimed at enhancing socio-economic development, financial integrity and corporate governance, as well as tackling corruption and financial irregularities are in order, the submission is that the extant proposals strike a disproportionate balance against civil liberties and arguably infringe established constitutional rights.

There is no reason why an honest loan defaulter, should not be able to access accommodation, nor obtain a driving licence; if both are required for financial and socio-economic rehabilitation; subject to the defaulter’s transparency with his/her lenders. Credit reference agencies should be subject to clear regulatory oversight and a robust code of conduct to avoid misusing citizens’ personal data.

Furthermore, the case for streamlining official documents is overdue. Nigeria, in 2025, should be in a position to develop a singular biometric card which integrates a citizen’s data to save the latter the cost and inconvenience of purchasing a million official identification documents to employ a hyperbole!

A review of the impacts of this policy, with critical input from key stakeholders in the legal profession, financial services, civil liberties and rights organisations, and security is therefore overdue! Action!! Now!!!

Ojumu is the Principal Partner at Balliol Myers LP, a firm of legal practitioners and strategy consultants in Lagos, Nigeria, and the author of The Dynamic Intersections of Economics, Foreign Relations, Jurisprudence and National Development (2023).