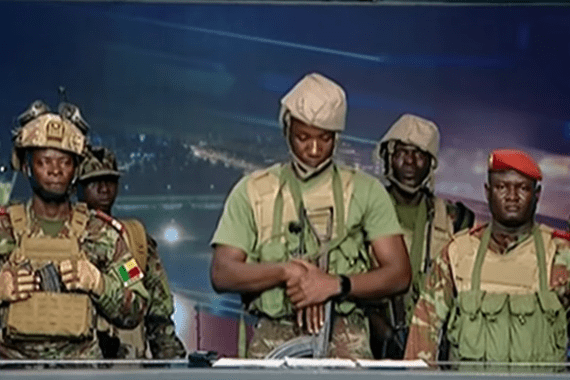

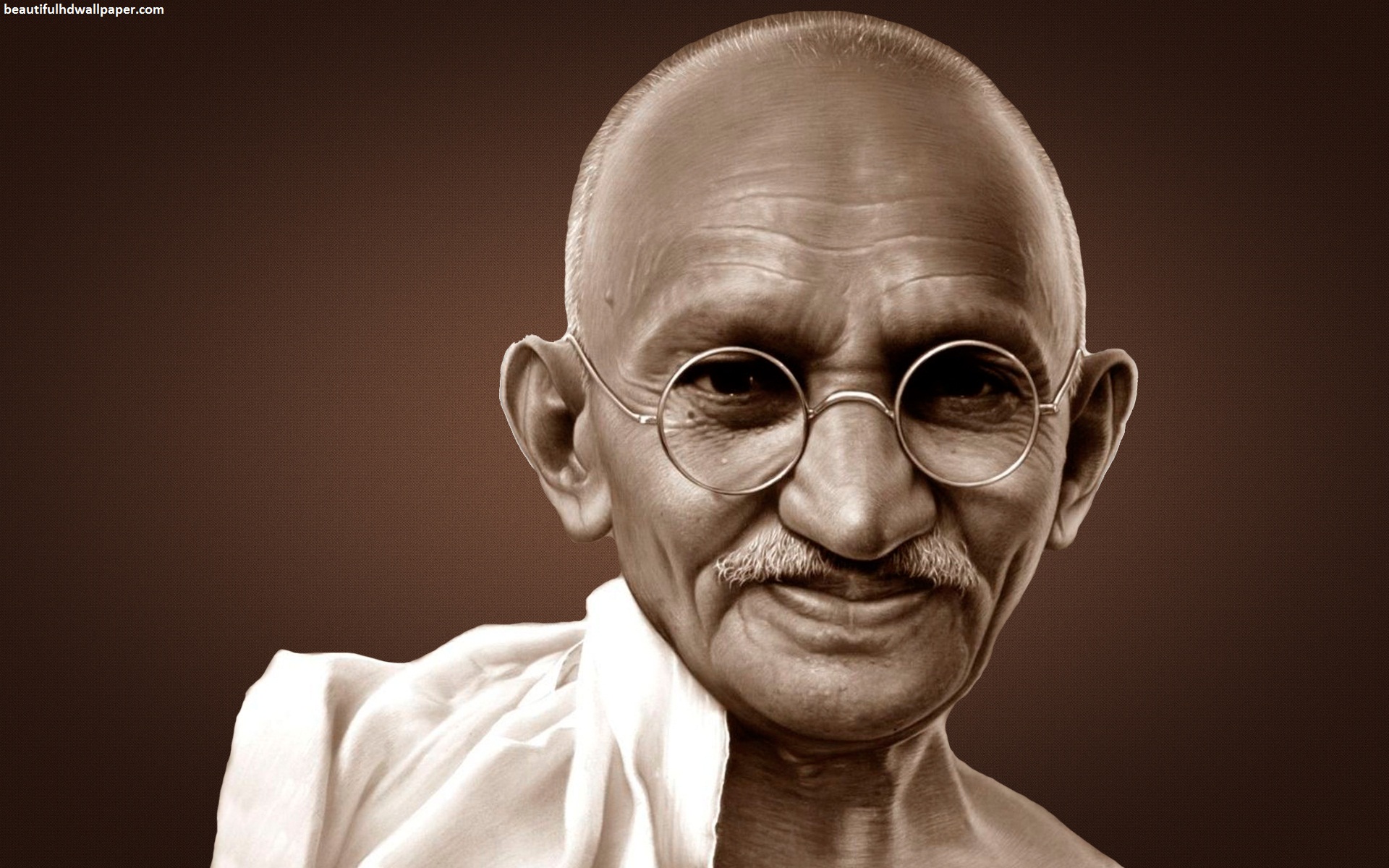

In all Gandhi who was assassinate on 30 January 1948, lived in South Africa for twenty years. Born in 1869 of a trading community – the Banda caste – he broke his caste taboo by travelling to London at the age of 19 to study law.

The years in London, although difficult for a shy teenager gave Gandhi unfettered freedom to explore life. He discovered vegetarianism and the Victorian ethic of self-help.

On his return to India he could not establish a legal career partly due to his shyness. He accepted a legal brief which made him migrate to South Africa in 1893.

He lived in Durban and Johannesburg and handled cases for rich Indian business men and sugar cane farmers. Over time he had a successful legal practice.

More and more though, he found himself defending the rights of Indian workers and indentured labourers.

[related ids=”628587″]

Much later still, he concerned himself with helping Indians to achieve a better racial classification in the apartheid state of South Africa.

Of course, he would have been aware of the situation of Africans in the South African political and economic arrangement. The Anglo-Boer War 1899 to 1902 renamed in post apartheid times as the South African War took place while Gandhi lived in South Africa.

The Dutch farmers and the British fought each other to see who would control the country. And the historical records of the Afrikaners (the Dutch) and the English (the British) say nothing about the role Africans in the war.

Yet Africans fought on both sides. When the British and the Dutch buried the hatchet, they buried it in the back of the Africans by setting up the Union of South Africa in 1902 in which Africans had no rights of citizenship.

And when the British set up their detention camps during that war to control the movement of their then enemy the Dutch, these Afrikaner farmers took their African slaves with them to such detention camps.

It is usually claimed that Gandhi was committed to achieving a better racial classification for Indians as members of the aryan race along with the British empire rulers. He volunteered as a stretcher career during that war.

In 1906 there were uprisings by the Zulu against the British colonialist in KwaZulu Natal. Why didn’t Gandhi support the Zulus against the British army? In response he is quoted as answering thus: “It is not for me to say whether the revolt of the Kaffirs is justified or not.”

Apart from the use the offensive k-word here, there is the obvious observation that Gandhi did not find common cause with the Africans while he fought for the rights of oppressed Indian workers and indentured labourers. Africans had begun organising themselves to fight apartheid at this time.

Both the 1902 settlement and the more damaging land act of 1913 brought great suffering to Africans. It was to better fight the whites, both Dutch and British that African National Congress was founded in 1912.

On 7 June 1893 Gandhi was travelling from Durban to Pretoria on official business as a lawyer. He had a first class ticket and he was seated in the first class compartment.

At the Pietermaritzburg railway station a European traveller in the same compartment ordered that passenger looking like a ‘coolie’ (derogatory term used for Indians by Whites in South Africa) be thrown out. The following is how phrases his dilemma on the occasion:

“Should I fight for my right or go back to India, or should I go on to Pretoria without minding the insults, and return to India after finishing the case? It would be cowardice to run back to India without fulfilling my obligation.” From MY EXPERIMENTS WITH TRUTH by MK Gandhi.

The Pietermaritzburg Station was named after Gandhi in 2011 Gandhi stayed on in South Africa for the next 22 years honing his signature contribution to modern politics and modern life satyagraha usually translated as non violence protest.

In 1897 in Durban Gandhi was beaten thoroughly and left bloody by a white mob bent on lynching him. In 1908 in Johannesburg he was assaulted by a group of violent Pathans. In all these attacks Gandhi trained himself and his followers to turn on the other cheek.

He founded the Natal Indian Congress in 1894 to fight against discrimination against Indians in South Africa.

All over the world from Europe to the Americas and back to Africa the ideology of non violence protest got supporters. From civil rights leaders in the United States of America to the anti apartheid protesters in Africa Gandhi was the leader to follow to gain power from powerlessness.

Gandhi’s struggle contained contradictions that he has to resolve as he struggled along. His struggled against British colonialism in India needed to unite Hindus and Indians.

His fight against untouchability and the Hindu caste system meant that he had the Brahmins and other higher caste as enemies.

In advocating a secular morality he had all religious organisations against him.

The point seems to be about determining whether we take Gandhi as a politician or as a social reformer.

And a politician who never headed an army or a government, a social reformer with no coercive forces to ensure his way among his followers. How far would non violence go to protect him?

In 1948, after partition and the independence of India and Pakistan, India renamed on its promise to give 550 million rupees from the joint budget. Gandhi embarked on a fast unto death to force India to give the money to Pakistan.

A group of Hindu nationalists who saw him supporting Muslims against Hindustan (India) responded that they would not let fasting kill him. Rather, he would be killed by their bullets.

So said, so done. On 20 January 1948, they attempted to kill him and failed. Then on 30 January 1948 Nathuram Godse, one of the conspirators shot Gandhi three times from point blank range.

Seven of the Hindu nationalists were tried and some went to goal while Godse and another were hanged. Gandhi’s death might be a political failure, but it was a moral triumph. India had to pay Pakistan.

[email protected]

[ad unit=2]