Jean-Michel Basquiat enjoys a stratospheric following — earlier this year, a 1982 oil painting by the late 20th century great became the most expensive work by a US artist ever sold at auction.

But 29 years after his death, his legacy is largely a triumph of popular culture over museums, which have been accused of downplaying his stature.

New York is where the black artist — son of a Haitian father and Puerto Rican mother — was born and raised, spent most of his life and drew most of his inspiration.

On May 18, it was in the Big Apple that one of his paintings fetched $110.5 million at Sotheby’s, jettisoning him into a pantheon of high-selling greats like Picasso.

Yet America’s cultural capital has no public monument to him, no institution named after him and has preserved none of his famous graffiti — signed “SAMO”.

Other than a plaque nailed to his former atelier in a NoHo back street, his simple gravestone in Green-Wood cemetery is perhaps the only place that tourists, admirers and budding artists can visit in tribute.

“There’s a lot of interest,” says Lisa Alpert, vice president of development and programming at Green-Wood. “They leave things on his grave.”

‘White privilege’?

Out of the more than 2,000 works of art that Basquiat produced, New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) has just 10 drawings and silkscreens, the Whitney has six, the Metropolitan two, the Brooklyn Museum another two and the Guggenheim one.

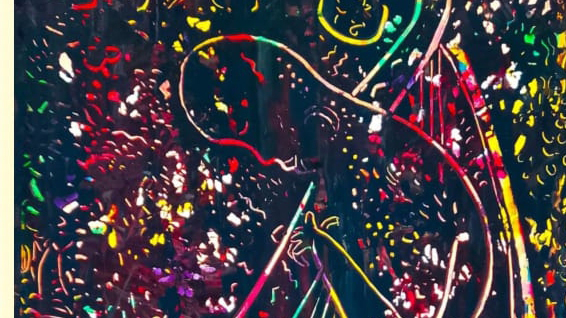

Much of his work fused drawing with painting it was abstract and figurative, offering biting political commentary on social problems such as poverty, segregation, racism and class divides.

Commercially successful in his short life, before his death from an overdose at 27, museums were nonetheless unconvinced that his work had weighty artistic merit.

Friend and artist Michael Holman remembers, for example, an offer by collectors Lenore and Herbert Schorr to donate Basquiats to MoMA and the Whitney in the 1980s, but says the museums declined, not even wanting them for storage.

“There’s a lot of racism and a lot of white privilege in the idea that only white people are important artists,” says Holman.

Celebrity favorite

Unlike his contemporaries, Basquiat never received a large solo exhibition at a New York museum during his lifetime, says Jordana Moore Saggese, an associate professor at the California College of the Arts, and the author of the only art history monograph of Basquiat.

“Historically there has also been a lack of representations for non-white artists in mainstream institutions,” says Saggese, who notes that few undergraduates are even taught much about him.

But many critics in the late 1970s and 1980s also championed minimalism and fretted that art in the 80s was too closely aligned to capitalism, she says.

They were “deeply divided over the question of whether an artist could be both commercially successful and critically significant,” she told AFP.

During his lifetime and even more so now, few museums can afford to acquire Basquiat’s work. Instead their best hope is to wait for wealthy collectors to perhaps bequeath his work in the coming decades.

Beyond blockbuster exhibitions in cities such as Basel, Paris, Rio de Janeiro and Toronto, Saggese estimates that 85 to 90 percent of Basquiat’s work is in the hands of private collectors.

Leonardo DiCaprio, Bono, Jay-Z, Johnny Depp and Tommy Hilfiger are just some of the celebrities to own or have owned a Basquiat.

While some New York galleries have bought and sold his work, that is more rare now that his paintings sell for such dizzying sums at auction.

Rick Rounick, owner of New York gallery Soho Contemporary Art, said he had nine paintings just a few months ago, but now has only two left.

Yet Basquiat’s appeal lies far beyond the hallowed institutions of fine art.

“With the rapid circulation of images and ideas via social media networks, artists like Basquiat are no longer as dependent on the traditional image machine of art criticism or art history for visibility,” ventured Saggese.

Popular culture

Japanese clothing brand Uniqlo has reproduced Basquiat imagery on T-shirts, sneakers, watches and tote bags in collaboration with MoMA.

Urban Decay has also released a set of makeup and accessories with licensed Basquiat imagery.

Jay-Z, Kanye West and A$AP Rocky rap about him. Canadian singer The Weeknd used to sport his hair in Basquiat-style dreadlocks.

There are movies and documentaries about him including “Downtown 81,” in which the young charismatic artist played himself aged 20.

“One could argue that in the years since his death, Basquiat’s presence is more emphatic in popular culture and mass media than in art museums,” said Saggese.

There’s even a children’s book, written by Javaka Steptoe and called “The Radiant Child,” to introduce him to the next generation.

“Children love him because his artwork and their artwork is similar,” says Steptoe. “He gives them permission to be what they are.”Holman says his friend changed not only the art world, but street art and fashion.

“He’s given so many young people, especially young people of color, in this city the license to believe that they could be important artists,” he said.”He’s a hero to young people the way Warhol was to my generation.”