The absence of structured creative-writing courses in Nigeria poses a significant threat to the nation’s creative industry, despite government projections that the sector could grow into a trillion-dollar component of the economy.

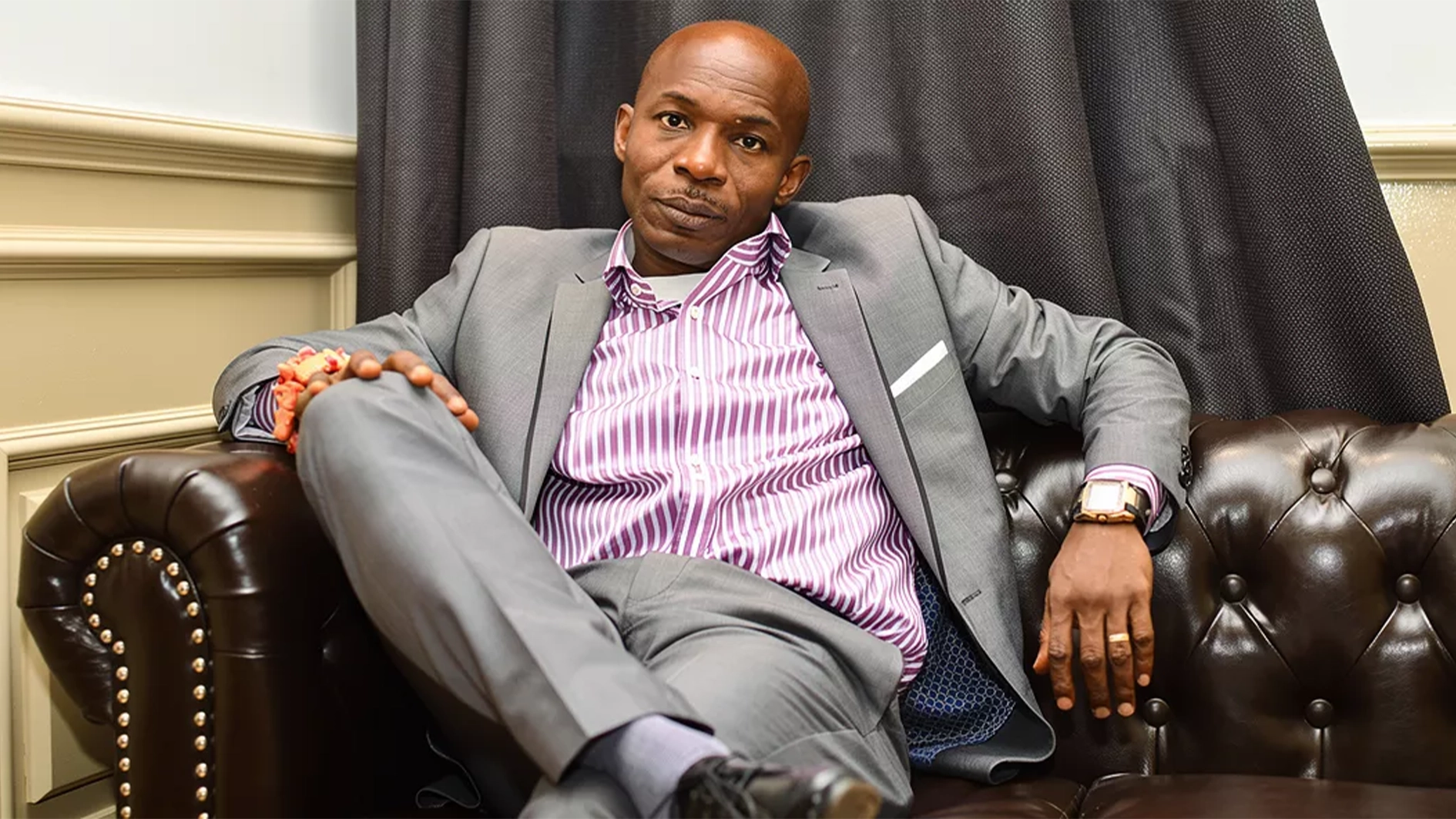

Nigerian-American playwright, poet and producer, Cash Onadele, speaking in Lagos during the launch of a pilot creative-writing workshop masterclass series, noted that while Nollywood contributes an estimated N3.2 billion to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), the industry remains far from achieving its projected growth due to weak storytelling and limited creative-writing capacity.

“When I searched Google for ‘creative writing courses in Nigeria,’ I expected to find a few institutions offering young Nigerians an entry point into storytelling, but regrettably found none, zero. We cannot build a trillion-dollar economy if we do not strengthen the very bedrock of creativity: writing,” he said.

He argued that the quality gap in film, theatre, media, and literature reflects the country’s neglect of writing as the primary skill that drives all creative industries. He also linked the withdrawal of some global streaming platforms, including Netflix, in part to poor storytelling standards.

“When stories are good, they are good. If they are not good, the question becomes: why are they not good enough?” he noted. “If our stories are weak, our industry will be weak,” he said.

Onadele stressed that young Nigerians, aged 15 to 35 years, remain custodians of cultural memory and must be taught to write the stories passed down by older generations. “Stories are the soul of every creative industry,” he said.

The five-day workshop provided a foundational creative writing course for secondary school leavers, tertiary students, and young creatives. Partnerships with YABATECH, LASU, and UNILAG were established to identify promising students lacking formal writing training.

The pilot cohort consisted of 68 participants selected with support from the Wole Soyinka International Cultural Exchange (WSICE) and the Committee for Relevant Art (CORA). It was learnt that many already had short stories drafted but lacked guidance on shaping them into world-class material.

Onadele said he developed 21 creative-writing modules covering story structure, dialogue, character development, and a complete learning pathway designed to take beginners from raw talent to industry-ready writers.

“We want to take people from nobody to somebody — just through story,” he said.

Although early support came from FCMB and private donors, the initiative remained largely self-funded. “With support from sponsors like the Bank of Industry or other partners, we can scale fast and train up to 1,000 youths monthly,” he said. “Even without that, we will continue at a small scale, because these skills can create jobs and change lives.”

He called on government agencies, development partners, private-sector groups, and philanthropists to recognise creative writing as a strategic development tool and invest in youth-focused programmes.

“If we want a future where Nigeria’s creative economy competes globally, we must invest in the people who create the stories,” he said.

Onadele also urged the Presidency to serve as the grand patron of the programme, aligning with the administration’s Renewed Hope Agenda, adding: “If we want a trillion-dollar creative economy, we must build it from the ground up. Let’s train our young people to tell their own stories with excellence.”