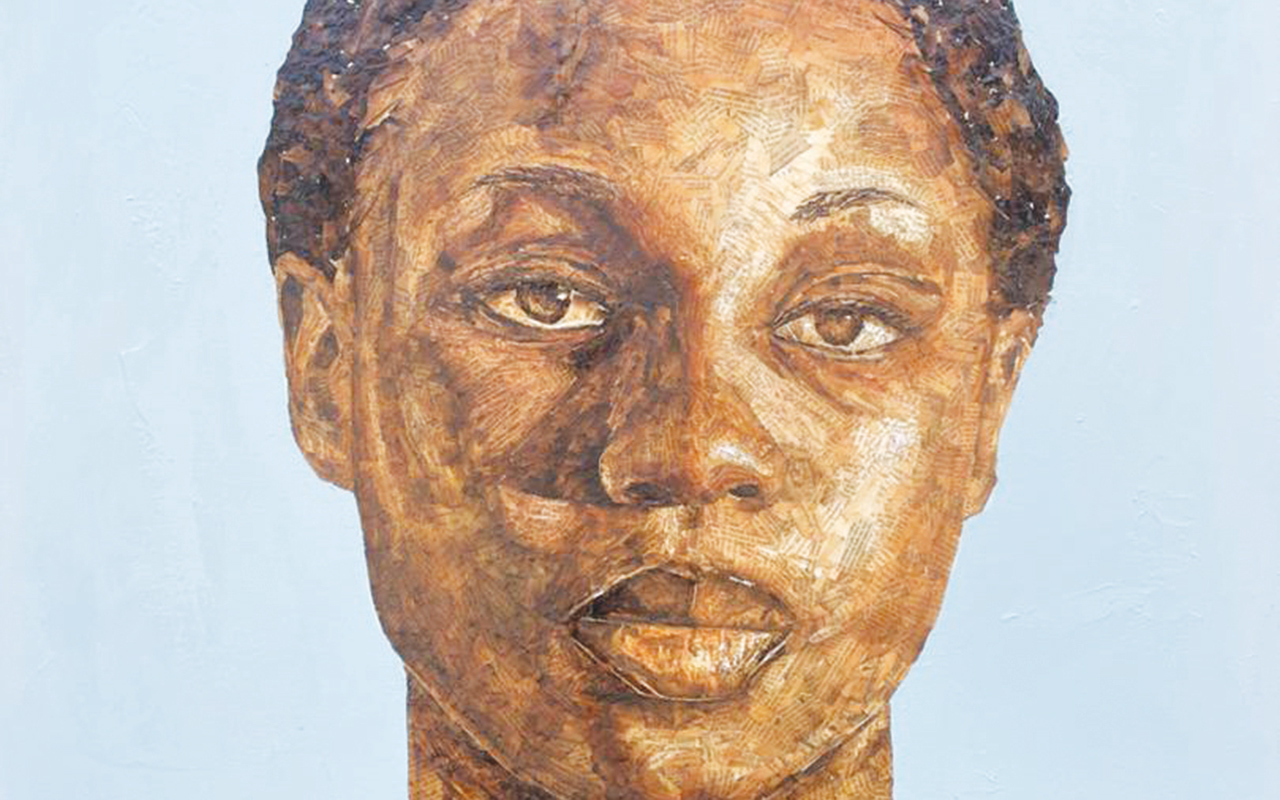

“We are mourning the loss of our father, husband and grandfather, Prof. Bankole ‘Kole’ Omotoso, who passed away after a long period of illness in Johannesburg on July 19, 2023.”

That was how the family of Kole, the late Professor of English and renowned writer, announced his death in a terse statement.

“A born scholar, he never missed an opportunity to engage in new topics. An astute socio-political critic, his criticality never got in the way of his belief in humanity. We will miss him,” the family added.

Born in Akure, Ondo State in 1943, the late Bankole Ajibabi Omotoso, popularly known as Kole Omotoso, was raised by his mother and maternal grandparents after the death of his father.

Though, the lack of a father figure could crush a young Nigerian boy, the events of his early childhood contributed a great deal to his development as a man and also as a writer. He went on to become a writer for different magazines in the 70s. He also wrote a number of columns in African newspapers, most notably, the Trouble Travels column in Nigeria’s The Guardian on Sunday from 2013 to 2016, which he has finally rested to be with his maker.

Kole attended King’s college, Lagos for secondary education and later went on to study French and Arabic at the University of Ibadan and then to the University of Edinburgh where his doctoral thesis was on Ahmad Ba Kathir, a modern Arabic writer.

He returned to Nigeria to teach Arabic at the University of Ibadan and after a short while moved to University of Ife, now Obafemi Awolowo University, to work in drama.

Professor Omotoso had to relocate to South Africa after his extensive works, including the 1988 publication of his book, Just Before Dawn, landed him in serious political trouble in Nigeria. Then, he was considered as one of those academics who were teaching students what they were not paid to teach.

From 1989, he was forced to work mostly outside of Nigeria. After visiting professorships in English at the University of Stirling and the National University of Lesotho and a spell at the Talawa Theatre Company, London, he became a professor of English at the University of the Western Cape in South Africa (1991–2000).

In the interest of reuniting the family, in 1992, the Omotosos relocated to Cape Town where Kole held professor positions at the English Department of the University of the Western Cape and the Drama Department of the University of Stellenbosch.

Like the Russian poet, Joseph Brodsky (May 24, 1940 – January 28, 1996), wrote of his beloved Venice, “I’d never possess this city… But then, I’d never had any such aspiration.” He wrote about the city as a space that welcomed him with familiarity yet gave him longed-for anonymity.

From the early 1990s, as the winds of democracy were blowing in South Africa, and immediately after 1994, when Vodacom was issued with a licence to operate in South Africa, Omotoso was the face of its adverts, with his image dominating the advertising media landscape.

He became one of the most visible persons in the country, reflecting the changing face of a new South Africa. He gained popularity as the ‘Yebo Gogo’ (Yes! Grandma) campaign for Vodacom.

For the Yebo Gogo man, South Africa formed a consciousness in him that Akure or even Nigeria couldn’t.

The Rainbow Nation created for him a demonstrably different tone of intellectually existence, and its imprints on him. He became a South African legend. He obtained South African citizenship in 1999. In fact, Omotoso was once described by the late South African President, Nelson Mandela, who was a family friend, as “the most photographed man in South Africa” due to his iconic Yebo Gogo folksy character portrayal, through which he became one of the most ubiquitous figures in South African popular culture.

On his 80th birthday, on April 24, former President Muhammadu Buhari described him as a scholar who has an exceptional understanding of African history, culture and its significance in the global community.

Buhari had praised his acumen for mainstreaming traditional icons, folklore and values for humanity in his books, and drawing attention to the need for balance in relationships.

HE was known for his dedication and commitment to fusing a socio-political re-appraisal of Africa and respect for human dignity into most of his works.

He grew up during the rising tide of radical nationalism and was enamored by the potential that lay in the future of the country. However, with the ascent of social and political decay, a few years after independence, Kole became deeply interested in writing about fiction.

Literature, for him, was an avenue that existed, apart from the decay of real life and where deep re-constructions about life and ideas, opportunity to experiment on social and political ideas for societal change and advancement.

From The edifice (1971) to The combat 1972; Miracles and other stories (1973) and Fela’s choice (1974) among others, he interroated a reality that will set humanity alright.

His other work include, Sacrifice (1974); The curse (1976); The Scales (1976); Shadows in the horizon (1977), a play about the combustibility of private property; To borrow a wandering leaf (1978); The form of the African novel: a critical essay (1979); Memories of our recent boom (1982); The theatrical into theatre: a study of the drama and theatre of the English-speaking Caribbean (1982); All this must be seen (1986); Just before dawn (1988); Season of migration to the south: Africa’s crises reconsidered (1994); Woza Africa = Oh Africa: quand la musique défie la guerre (1997) and others.

Though the programme was to later receive negative attention, in 2003, Big Brother Africa enlisted Omotoso’s expertise on cultural dynamics bound to govern content emanating from the house. No doubt, Omotoso’s cultural input will be seen in the maiden edition won by the Zambian, Cherise Makubale and hosted by Mark Pilgrim.

On May 5, 2004, while giving the third in the Rhodes University Centenary Lecture Series, in reporting the lecture, the University also drew attention to the Yebo Gogo reputation.

Speaking to a full house in Grahamstown, Omotoso captivated the audience with his talk, entitled, ‘Is White Available in Black: The Trickster Tradition & The Gods and Goddesses of the Cultures of Down-pression’.

His lecture was brushed with humour and examples from folktales “where the culture of the oppressed flourishes.” He challenged the English word for oppression as the oppressed do not feel ‘op’ or ‘up’ but are rather pushed down hence his terminology ‘down-pression’.

“There is a way in which those who are oppressed eke out a living. Jews, Blacks, Women, Gays, Disabled, Children, Pensioners and Animals, all oppressed one time or another in the course of History, develop mechanisms for their existence. The daily rituals of their lives come to constitute cultures in their own rights, cultures that do not receive much attention from those who concern themselves with the study of the dominant cultures of our societies. What usually interest savants of cultures are the struggles of the oppressed against their oppressors.

But the struggle against oppression is not the first thought of those oppressed. Their first concern is to get on with living their lives with the minimum pain – physical, mental and psychological – possible. To do this, they evoke a number of deities who have come to be known as the Trickster Deities. My concern in this lecture is to look at these Trickster Gods and Goddesses of the Black oppressed and marvel at their ability to live on beyond the oppression of those who evoke them, in this particular case, the Blacks. But we have some way to go before we get to those deities,” said Professor Omotoso.

“There was no attempt by any of the little victors to turn themselves into the mighty one they overcame. The achievement of victory through mental activity rather than through mere muscle proclaims the superiority of these little creatures over their oppressors. The oppression might continue but it would continue for others, not for them. They have conquered the oppressor although oppression continues its triumphant stride through human history,” he explained.

Professor Omotoso then introduced to the discussion another method of cultural expression for the oppressed – the PHD syndrome an acronym for ‘Pull him/her down’. “Nobody in the community of the oppressed and the poor is allowed to grow taller than the rest. Mechanisms are put in place to ensure that this does not happen. In Igbo society for instance, nobody could really have so much as to become the king over the rest. Before you can become king you must feed the community for seven years without fail. If you still have something left by then, you must then pay the debt of everybody in the society. By this time you would not have anything left with which to take the title of king.”

In closing his lecture Professor Omotoso touched on the ambivalence of Africans in the face of development. He said it reminded him of a notice on the door of a civil servant in a government office somewhere in Abuja, Nigeria with a notice ‘Silence! Development going on!’

“It is clear that we are still clueless how to deal with development, how to bring it about and having brought it about, how to live with it while at the same time living with our culture. And remember that what is said to be our culture is the culture that developed under a different socio-economic paradigm. We bemoan the break up of the family, the disintegration of the community and the absence of Ubuntu when it should be clear to us that such are the consequences of development! It has happened in other societies and it will happen in ours in spite of the favours accorded multi-culturalism. Occupying the moral upper ground is the prerogative of the poor and the oppressed. When we are developed and no longer poor and oppressed, we must give up this position. But some would say that we are generally still poor and oppressed given the nature of our numbers in these sectors. But this is like saying that if you have your feet in a bucket of ice and your head in a hot oven you are cool on the average. Much has been made of transition and transformation. Is this a transition or a permanent habitation of a pit stop? Can transformation take place without socialisation?”

He continued: “We in South Africa need to revisit our rainbow nation. If we do not mix the colours of the rainbow in the nation we are trying to build we end up with all our colours standing apart. That mixing can only take place through socialisation. The Tortoise does not wish to become the Elephant or the Hippopotamus. The Hare does not wish to become the Lion. Neither does Ti-Jean intend to turn himself to the Devil. Each of these creatures would like to combine the strength of their masters and oppressors with their own wily natures to make a better life for themselves and their erstwhile oppressors. In fashioning the culture that would make this possible, the socialization of the peoples of the country that wishes to transform is imperative. Merely making white available in black does not produce the positive result that we all hanker after.”

OMOTOSO, whose area of specialisation was drama, theatre and performance studies, was respected for his ability to deeploy languages from global divide, had told an interviewer after his famous commercial, Yebo! Gogo (Yes! Grandma) campaign for Vodacom: “My special area of concentration is African theatre and drama, and I speak the languages that make this area my own: Arabic for North Africa; French for francophone Africa; English, of course, and Yoruba, one of the major languages of theatre and drama in West Africa.”

MEANWHILE, Vodacom has paid tribute to Omotoso, widely recognised as the face of the company’s long-running ‘Yebo Gogo’ advertising campaign.

Vodacom Group CEO Shameel Joosub said in a statement: “We are deeply saddened by the news of the passing of Prof Omotoso, who is one of the country’s respected academics and playwrights. We remember him as an iconic figure who helped put brand Vodacom on the map through the inventive ‘Yebo Gogo’ advertising campaign that went on to win several advertising accolades.

“I would also like to offer my personal heartfelt condolences to Prof Omotoso’s family.“He leaves behind a rich legacy, having played a significant role in inserting brand Vodacom, a brand with deep African roots, into the national consciousness. I would also like to offer my personal heartfelt condolences to Prof Omotoso’s family,” Joosub said.

HE was married to Marguerita Omotoso, an architect and urban planner, originally from Barbados. He is survived by his wife and three children — including actor, director and filmmaker, Akin; Pelayo, the engineer and Yewande, the author and architect.