Unwana Efiong’s crusade on Charcoal has been quite the spectacle in my musings lately. Her intimate collection at the Boring exhibition curated by Holy Art, where I first observed her work, soulfully perceives the beauty of community and co-dependence.

Unwana Efiong’s crusade on Charcoal has been quite the spectacle in my musings lately. Her intimate collection at the Boring exhibition curated by Holy Art, where I first observed her work, soulfully perceives the beauty of community and co-dependence.

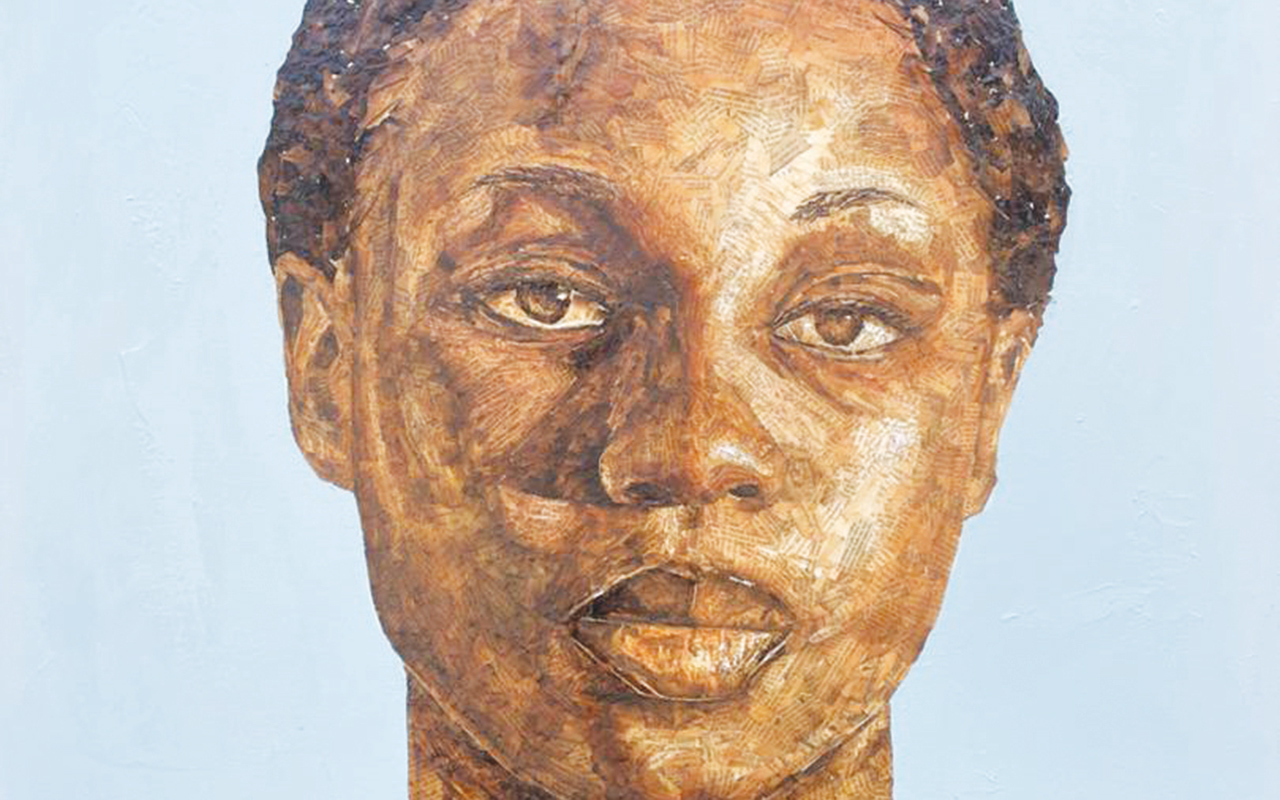

The Nigerian visual artist, architect and mental health researcher first evoked nostalgia, with her choice of hue — a dimly lit brownish shade — principally setting her ideas to feel transcendental and evergreen. It’s a delicate concept, one which I have seen explored by other contemporaries like Michael Bartmann, Jacqueline Boyd, and even older generations like Jean-Michel Basquiat, among others. What is most captivating about the hue on Efiong’s portraits are her interesting contrast of light and shadow, painted as if the Sun was flickering its hair on the surface.

The artworks also conveyed a vivid sense of family or co-dependence. The first portrait titled, A Different Kind of Love, spotlights a young boy, seemingly aged between 10 and 15, piggybacking his baby brother. The other portrait dubbed, The Threshold of Time, shows two middle aged men, likely colleagues, dragging an oversized key down a windy path. And the last portrait, A Tale of Care, sees a young child cradling a lamb, with a smile bigger than her confident body. All the artworks point to themes of unconditional support, love and dependence, reminding one of the unparalleled value of community.

Efiong’s penchant for creating characters without the flamboyance of forced finesse, without the need for perfectly smooth chins, shaped eyes, or head shapes, is admirable. She leaves the characters as their stories guide them to be, brilliantly crafted with charcoal and candour. The large-sized foreheads of the children, with their receding hairlines, is a good example of Efiong’s unfiltered perceptions.

Efiong’s portraits howl with an understanding between the beholder and the subjects. It feels like a conversation on the ethics of her portrayal of them, especially around their prominence in Efiong’s subconscious, which isolated them ab initio from the myriad other fragments of reality that sit within her thoughts. They feel like they deserve to exist, just because they’re real, and they’re part of the creative process of reality itself. Basically, art that is mostly underlooked, but is always staring you dead in the eyes every single day.

It’s interesting to also note the ting of culture, with scenes of the bare-chested child tying a wrapper across his waist — a common fashion style for teenagers in rural villages across Southern, Western and Eastern Nigeria — and a catapult hung around his neck in A Different Kind of Love, or the shepherd culture of Northern Nigerians, coupled with what looks like a miniature dashiki on the child holding a lamb in A Tale of Care. The portraits also showcase the reality of life among Nigeria’s lowest-earning social class, with children often left to wander or tend to animals during the day, or having to hunt at young ages not for fun but for survival.

The nut graph in Efiong’s work is that it feels cohesive, and it surely is a poignant interpretation of life, as simple, as shared, and as chaotic as it can be.

Based in the United Kingdom, Unwana Efiong is a multifaceted artist with a spontaneous and versatile approach to art. She uses a variety of techniques, such as scribbling, hatching, and blurring, without adhering to a fixed style, allowing her creativity to flow naturally. Her work spans both traditional and digital mediums, often reflecting themes of mental health, empowerment, and social impact. Efiong’s art is shaped by the strongest themes in her personal journey and the seasons of life. She also draws inspiration from Nigerian history.