The recent release of General Ibrahim Babangida’s memoir, A Journey in Service, has stirred widespread debate, with scholars and analysts questioning whether the book represents an honest self-examination or an anxious attempt to shape how history remembers him. At The Toyin Falola Interviews, a virtual intellectual forum held on Sunday, experts argued that the memoir was motivated by Babangida’s deep-seated concern over his historical legacy, rather than a genuine reckoning with his controversial years in power.

Professor Moses Ochonu of Vanderbilt University contended that Babangida’s decision to write the book was primarily driven by fear — fear of being misrepresented, fear of losing control over his narrative, and fear of being remembered solely for his missteps.

According to Ochonu, Babangida’s memoir aligns with what Achille Mbembe describes as Africa’s mode of self-writing, a deliberate effort by political figures to reclaim and redefine their historical image. “As humans, we are naturally disposed to controlling the stories about our lives,” Ochonu said. “We don’t want others to define us; we want to define ourselves.”

The historian argued that Babangida’s carefully cultivated mystique—his reputation as Nigeria’s most enigmatic ruler, known for his tactical evasions and political maneuvering—worked in his favour while he was in power but became a liability in retirement. “When he was in power, this aura of mystery served him. But in retirement, that same mystery has become a burden on his legacy,” Ochonu observed. “This book is his attempt to demystify himself and create a controlled archive of how he wants to be remembered.”

Veteran journalist, Azubuike Ishiekwene, another panelist at the discussion, took a critical stance, arguing that Babangida’s memoir is marked by selective omissions. He pointed out that the former head of state, despite dedicating chapters to his policies and decisions, failed to fully address his role in some of Nigeria’s most consequential political crises, including the annulment of the June 12, 1993, presidential election and the execution of the Ogoni Nine. “You share what you are comfortable sharing, and you omit what you do not want to be remembered for,” Ishiekwene remarked. “As far as Babangida’s memoir goes, the unsaid might be more interesting than what is said.”

Ishiekwene further criticised Babangida’s portrayal of his relationship with the press, noting that the former ruler’s claim of supporting a free press is at odds with his administration’s well-documented history of media repression. “In 1993 alone, Babangida shut down 25 newspaper houses. The year before, he shut down 41,” he recalled. “You cannot erase that part of history just because you choose not to write about it.”

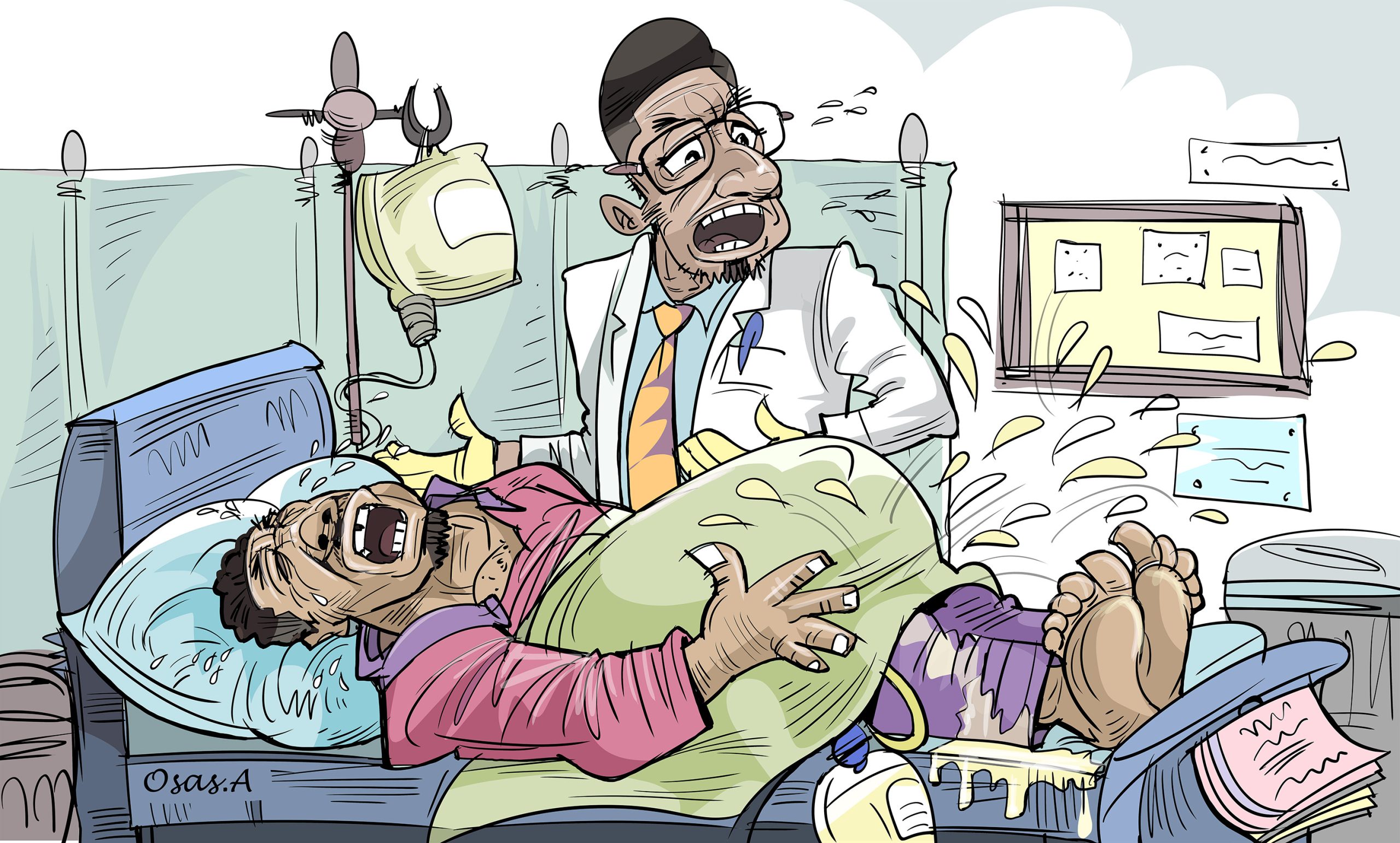

Former senator and journalist, Babafemi Ojudu provided a more personal insight into Babangida’s state of mind. He recalled visiting Babangida twice after he left office and was struck by the former leader’s reluctance to write a book at the time. “I asked him point-blank, and he said he would never write a book. The question now is: what changed?” Ojudu asked. He speculated that Babangida may have come to view the memoir as a last chance to influence how history will judge him. “This is a tortured book from a troubled mind,” he remarked. “You can imagine the kind of global image he would have cultivated if he had allowed the June 12 election to stand. But he annulled it, and now he lives in regret.”

Wale Lawal, a publisher and political analyst, also weighed in, emphasizing that Babangida’s attempt to shape public memory will not necessarily change the way Nigerians perceive him. “In many ways, history is the last frontier of justice,” Lawal stated. “No matter what he writes, the way Nigerians feel about him will remain the same. This book is not about correcting history—it is about controlling public memory.”

Lawal dismissed the idea that the memoir represented a moment of reckoning for Babangida. “I don’t necessarily see this as an attempt at reformation,” he said. “It is very difficult to process it as such. I don’t think we are that naïve as a country.” He urged Nigerians to read the book with a critical eye, particularly in terms of what Babangida chose to highlight and what he conspicuously ignored.