In this second and concluding part of the tour of primary healthcare centres in Ogun West and Ogun East senatorial districts, which revealed shocking scenes of lack and negligence capable of costing human lives, OLAYIDE SOAGA reports that these Basic Health Care Provision Fund (BHCPF)-funded facilities lack amenities, manpower and logistics to make primary healthcare truly accessible and affordable for Nigerians living in rural areas. Additionally, significant funding gaps are driving patients into the arms of private clinics that rely on auxiliary nurses.

The first time Bamidele Fadebi went into labour in Ibeku, a quiet rural community in Yewa North Local Council, her husband, Moruf, did not stop to weigh the options. He headed straight to a small private clinic within the community.

The same scene played out during her second and third pregnancies. Years later, Fadebi still finds herself returning to that same clinic, the only place she believes she can safely deliver her babies and receive care.

Had the community’s PHC been functional during her childbearing years, she would have delivered them there and sought treatment whenever she fell ill.

That said, what is playing out in the area serves as a reminder that healthcare facilities, when not properly managed, can become a shadow of their former selves, forcing residents to seek alternative options, even if it means entrusting their lives to private clinics that rely on auxiliary nurses, who lack adequate medical skills or knowledge for treatment.

This is the reality faced by residents of many Ogun communities where their community PHCs are either abandoned or struggling to operate amid conditions unfit to receive patients.

Abandoned, deplorable PHCs litter Ogun border communities

This investigation led The Guardian to communities in Ipokia and Yewa North local councils, where a shocking discovery was made: abandoned and deplorable PHCs litter the border communities, and residents of these underserved places must travel long distances to the nearest functional PHCs on poor, unmotorable roads.

A year after settling in Iponron, a quiet farming community in Ipokia Local Council of Ogun State, one of the local councils between Nigeria and the Benin Republic, Olorunwa Tapa, discovered that she was pregnant with her first child. She had moved there with her husband, a local farmer.

For her regular antenatal visits, Tapa chose a PHC in Tube, another community in the area. The roads leading in and out of her community, which had been unpaved since her husband began living there, were in the same deplorable condition when Tapa was pregnant with her first child. She had to miss her antenatal appointments on several occasions, especially on rainy days, because the roads were simply impassable.

The PHC in Tube, an hour’s drive from Iponron, was her only hope, as the facility in her community, just a five-minute drive away from her home, had been abandoned for years.

On the day she gave birth to Hannah, her first child, Tapa was deep in labour when she climbed onto her husband’s motorcycle, which was the only means of transportation available.

The couple set out for the PHC in Tube. Each bump on the rough, dusty road riddled her with sharp pain, but she held on tightly. After a long and exhausting labour, Tapa delivered Hannah, a healthy baby girl.

When The Guardian met her in October, Hannah had clocked a year, and Tapa was six months pregnant with her second child. The PHC in her community was still in the same condition. So, Tapa still attends the PHC in Tube for her regular antenatal visits.

She described the road to the Tube as a nightmare, which would have been avoided if her community’s PHC were functioning or if the roads in the community were motorable.

“The roads are terrible. It is the worst I have seen. It needs urgent repair. The poor road conditions make going outside the community very inconvenient. Whenever I get on a bike to go out of the community, I feel so much pain,” she said.

The Iponron Health Centre was commissioned in 2009. Almost two decades later, the health centre, which had served thousands of people who lived in the area, now stands empty, its rooms and hospital bed frames abandoned, its surroundings filled with overgrown weeds.

When The Guardian visited, mattresses strewn on the ground were said to belong to two young men who appeared to be in their 20s.

A resident of the community confided in The Guardian that the young men were road construction workers who spent their nights at the facility that they claim was being renovated, even though there were no signs of any major renovation work ongoing at the facility.

Tapa’s story reflects that of hundreds of other women in rural areas like Ipokia and Yewa North, where health inequalities are prevalent, and women endure long journeys to deliver babies, while residents travel long distances to get treated.

In Obanigbe, another community in Ipokia, the community’s only PHC stayed alone in the middle of overgrown weeds. Its signpost was rusty, and the inscription on it was barely legible. At the wards, where patients should have been, damaged hospital beds and debris struggled for space instead.

Hannah Oke moved into Obanigbe, a community in Ipokia Local Council, 10 years ago and met the community’s sole PHC in ruins. It was in that same condition when she got pregnant, and when she went into labour early in the year. Oke said she has become accustomed to travelling long distances in search of healthcare and no longer finds the commute stressful. Still, she appealed to the government to renovate the facility and restore it to its former glory.

“We want the government to fix the health centre. If it were working, we wouldn’t have to run helter-skelter for treatment, but since it is bad, we go to private hospitals or the PHC in Ipokia.”

One PHC Serving Three Communities

In Ohunbe Ward of Yewa North Local Council, the Asa, Ibeku, and Agbon Ojodu communities rely on the PHC in Agbon Ojodu for their health needs, as the facilities in Ibeku and Asa are non-functional.

When The Guardian visited Asa in October, it was discovered that the community’s PHC, which had been abandoned for years, had just been newly renovated. The renovation was facilitated by Senator Solomon Olamilekan Adeola, representing Ogun West in the National Assembly, as a constituency project. The renovation was completed last July.

Risikat Gbadamosi, a resident of the community who has lived there for over three decades, recalled that the once functional PHC had been abandoned as the years passed.

An investigation published by the FIJ in 2024 corroborated this. As of June 2024, when the report was published, the PHC was in a state of abandonment with its ceiling boards broken, while damaged hospital bed frames littered wards where residents seeking medical attention ought to be.

When Gbadamosi was pregnant, the PHC was not out of order, and that is the reason she gave birth to her children in Agbon Ojodu, a neighbouring community.

Kosolu Bilikisu, who has been residing in Asa since 2010, told The Guardian that she gave birth to her children in the PHC in Asa before it became abandoned.

Women are not the only ones bearing the brunt of the absence of a functioning PHC in the community. The community’s aged population is also feeling the impact.

For instance, when 91-year-old Olukookun Matthew, the community’s traditional head, began experiencing weakness, frequent headaches, and vomiting, the entire community grew worried. With their PHC non-functional and the nearest one, Agbon-Ojodu PHC, in dire need of renovation, he was taken across the border to the Republic of Benin for treatment.

When the PHC in Asa was renovated last July, the residents heaved a sigh of relief. However, the renovated PHC is yet to open to serve the community, as it was locked when The Guardian visited last October.

But Arowa Bolaji, a resident of Asa, informed The Guardian that the key was with the engineer who was in charge of the renovation.

While Asa’s residents are hopeful that their community’s PHC will be opened soon, giving them access to healthcare, this is not the case for residents of neighbouring Ibeku. For residents of Asa, Ibeku and Agbon Ojodu, the PHC in Agbon Ojodu is their only hope. However, the cracks have already begun to appear in the PHC, which was recently renovated.

During The Guardian’s visit, two female health attendants on duty informed that the PHC has no potable water, hence they must fetch water from elsewhere in the community to use in the facility. The PHC also lacks toilets, forcing patients to go into the bushes surrounding the PHC or an abandoned building nearby to relieve themselves.

Checks by The Guardian revealed that Asa and Ibeku PHCs are not on the NPCHDA’s website of PHCs.

Funding gaps force patients into private clinics

The Ogun State Primary Health Care Development Board enjoys a lump allocation from the state’s coffers annually. It, however, spends less than its annual allocation.

For instance, in 2023, the state government allocated the sum of N15,060,879,396.92 to the board, but it did not spend up to a billion that year. According to the budget performance for that year, the board spent the sum of N390,699,521.26.

In 2024, the board received an allocation of N24,779,036,589.56, but only utilised N415,979,818.80 from the total allocation. The board received an allocation of N35,904,484,335.82 for the 2025 fiscal year.

Another scheme was designed by the Federal Government to make healthcare accessible to Nigerians, particularly those in rural and underserved communities, called the Basic Healthcare Provision Fund (BHCPF). Under the BHCPF’s national guidelines, one of the key targets is that each political ward in Nigeria should have at least one fully functional primary healthcare facility participating under the fund via the National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA) gateway.

Every year, 0.5 per cent of the Consolidated Revenue Fund (CRF) of the federal government is allocated annually to BHCPF. The fund is divided into three parts. About 50 per cent of it is allocated to health insurance to cover the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) basic minimum package, targeting vulnerable populations at the primary care level, while 45 per cent is allocated for facility grants for direct operational support for PHCs, including drugs, basic equipment, and facility improvement and emergency health needs and special interventions get an allocation of five per cent under the reserve fund.

Funds are channelled from the Federal Ministry of Health to states, which then allocate them to local governments and PHCs. States and LGAs are expected to co-fund and manage funds to ensure accountability.

According to the latest NPHCDA Gateway updates presented by the Executive Director of the agency, Dr Muyiwa Aina, N52 billion has been disbursed to PHCs by the agency between 2023 and October 2025. It was also revealed that N14 billion was disbursed to facilities between the first and second quarters of 2025.

Ogun State received N458 million in 2023, N580 million in 2024, and N377 million between the first and second quarters of 2025. These funds are distributed between the 227 BHPCF facilities in the state.

When The Guardian asked the Ogun State Commissioner for Health, Tomi Coker, how much PHCs, which are beneficiaries of the BHCPF, receive from the scheme, she did not respond.

The BHCPF’s minimum requirement of at least one PHC per ward in the funding model leaves many PHCs without support, particularly those in states where governments tend to shy away from equipping health centres.

Those excluded facilities struggle with poor infrastructure, drug stockout, and understaffing. As a result, residents in those wards turn to private clinics, which are often established by nurses, sometimes doctors, who hire auxiliary nurses, because the public PHC meant to serve them receives no funding from BHCPF, and the state government fails to provide them with adequate resources to function properly.

According to Dr Joyce Foluke Olaniyi-George, a public health specialist with over two decades of experience, the one PHC per ward policy has its faults.

“For some areas like Lagos and some other smaller states that are not challenged by very large land masses and difficult terrains, this might not be a problem. But in most of Nigeria, with particular geographical distances that are very difficult to navigate, such that the one PHC beneficiary per ward policy will definitely not be sufficient,” she said.

Olaniyi-George suggests changing the policy from one PHC beneficiary per ward to one PHC beneficiary from one distance to another to ensure residents of communities like Ogun border communities have access to operational PHCs and quality healthcare without travelling far distances.

“What could have been done would have been to identify PHCs in a particular radius. For instance, to say there should be PHC beneficiaries from one end to the other. Maybe from a 50-kilometre, 10-kilometre or 20-kilometre radius, there should be a PHC beneficiary regardless of the ward,” she said.

Healthcare facilities established and funded by the government are many people’s first choice, particularly because they provide them with affordable healthcare, but when the government fails to equip them and provide the PHCs in their community with adequate funding, these facilities remain in ruins, and people are forced to either travel far distances to the nearest state-run health facility or patronise private health clinics.

In Ibeku, another community with an abandoned PHC, Felicia Fakanbi shares her troubles as well. Despite residing beside her community’s sole PHC, Fakanbi, who has lived there for the past 22 years, delivered her children in a private clinic in Agbon-Ojodu, a neighbouring community.

She has watched people come there to get treated, only to leave in disappointment after discovering that the PHC has been abandoned.

“Last month, some people brought a woman who was ill to this PHC, but they had to take her to Agbon Ojodu for treatment when they found nobody in the PHC here,” Fakanbi narrated.

She told The Guardian that whenever she or her children are ill, they visit the PHC in Agbon Ojodu or private clinics.

“I have been living here for 22 years, but the PHC has not been operational for years. I gave birth to my children in a private clinic in Agbon-Ojodu. It was not a great move to another community. When my children are ill, I take them to a private clinic,” she told The Guardian.

Poor medical interventions result in poor outcomes

Women and children often bear the brunt of the underfunded health sector and are at the receiving end of poor medical interventions, which leads to poor outcomes such as high maternal and infant mortality rates.

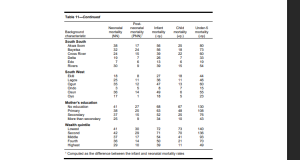

According to the Federal Ministry of Health’s Demographic and Health Survey, released in October, the southwest has the lowest rates of neonatal, postneonatal, infant, and under-5 mortality during the 10 years preceding the survey.

Ogun State, however, has the highest rate in the region.

Ogun State recorded the second-highest neonatal mortality rate in the South-West, with 35 deaths per 1,000 live births, coming just after Osun State at 36 deaths per 1,000 live births. It also had the second-highest post-neonatal mortality rate in the region, with 12 deaths per 1,000 live births.

In terms of infant mortality, Ogun ranked second again, with 47 deaths per 1,000 live births, following Osun State’s 49 deaths per 1,000 live births. The state’s child mortality rate was the highest in the region, at 13 deaths per 1,000 children aged 1- 4. Furthermore, Ogun State recorded the highest under-five mortality rate in the South-West, with 60 deaths per 1,000 live births.

According to research work, poor quality of care, which includes travelling a far distance to access medical care in the nearest functional medical centre, which is the harsh reality women in Ogun border communities face, contributes to newborn mortality.

“Other causes of mortality in newborns in Nigeria include poor quality of care. Health services are provided through both public and private sectors, with primary healthcare being a significant. But the accessibility of these services does not equate to good quality of care,” it read in part.

“Private health care service is poorly incorporated into Nigeria’s health system, even though it

plays a significant role in rendering care. Other challenges to optimal health care services include the distance to be covered to reach health facilities, especially in rural areas, the cost of services, disruption of services, poor quality of care, inadequate implementation of the standard guidelines, and attitudes of health workers to care of patients.”

This position is shared by Olaniyi-George, who explained that a delay in movement when a woman is in labour could compromise the life of the woman and the baby.

“Even before a woman is in labour, a woman having preeclampsia or eclampsia already fitting, a distance of an hour or two will definitely compromise the life of the mother and the baby, or a bleeding woman woman who has probably either not yet delivered in which case we talk about antepartum hemorrhage, if you don’t act within 15 to 20 maybe 30 minutes, you are going to lose the baby. The mother may still survive, but the baby will be lost,” she said.

She added that a delay in getting to the nearest functional medical centre could also cause complications during labour, such as shoulder dystocia, when the baby is stuck mid labour or cephalo pelvic disproportion.

“In that situation, the baby is stuck. How do you want to wait for an hour to get to the nearest facility? Obviously, you are going to be bringing out a baby that is probably not alive, asphyxiated or come out with developed cerebral palsy, and the mother can definitely suffer a lot of damage to the pelvis,” the doctor explained.

“The bones, soft tissue around that area can be compromised, and there could be bleeding, tissue damage. Then you can talk about things like the head of the baby pressing on the bladder wall, and at the end of the day, the woman develops a fistula where the urine leaks.”

Olaniyi-George added that the woman could also suffer mental health challenges after losing a child during labour or suffering any of those complications.

Private clinics are filling the healthcare gap with auxiliary nurses

In Nigeria, clinics and hospitals owned by individuals, corporate entities, religious organisations, or NGOs play a key role in health service delivery, often complementing or even replacing public facilities in both urban and rural areas.

In government-run hospitals and health centres, patients receive healthcare at subsidised costs, sometimes free of charge, but the reverse is the case in private hospitals.

Their fees are often higher than those of government-run hospitals and health centres.

For residents of rural and underserved communities who are low-income earners, these are unaffordable, leaving them to pay for healthcare through their noses, a situation that would have been prevented if government-run PHCs closest to them were functioning.

Fakanbi, who lives in Ibeku, echoes the sentiment, explaining that private hospitals are incomparable to government-run health centres in terms of cost and affordable healthcare.

“Private clinics can’t be like government clinics. There are some benefits we get for free at government clinics, but private clinics will charge us fees, which could be inconvenient for us,” she said.

In areas where public PHCs are under-resourced, private facilities handle deliveries, immunisations, and emergency care. They are regulated through a combination of federal, state, and professional regulatory bodies to ensure quality, safety, and compliance with national standards; however, some run afoul of these regulations.

Visits to six private clinics across Oja Odan, Ibeku, Odogbolu, and Iponron revealed a troubling practice: patients were being attended to by auxiliary nurses, despite clear prohibitions by professional bodies such as the National Association of Nigerian Nurses and Midwives (NANNM).

The founders of five of the six clinics visited by The Guardian admitted to not only employing but also training these auxiliary nurses within their facilities, highlighting a widespread disregard for established professional and legal standards.

In Ibeku, where Fakanbi resides, there is a private clinic operated by a man who claims to have graduated from a nursing school.

When The Guardian visited, Majolabi Sikiru, a grey-haired middle-aged man who is the founder of Mount Oliveth Clinic in Ibeku, was alone in the clinic. From the outside, the clinic, a bungalow with about three rooms, one of which served as Sikiru’s office, looked like any other house in the community. Stepping inside, it was hard to imagine that the space was intended for patients’ care.

When inquiries about his qualifications popped up, Sikiru said that he graduated from a nursing school. According to him, the clinic receives few patients and operates with one doctor and an auxiliary nurse.

In Iponron, the Iwoku Private Hospital, like Mount Oliveth Clinic, bore no semblance to a healthcare facility. Some women were outside underneath a shed; one sat on a plastic chair, while two others flanked her on either side. She was losing her hair, and strands of attachment littered the floor.

The woman who sat on the chair told The Guardian that she was an auxiliary nurse, and her “boss” was not available to respond to questions.

“I am an auxiliary nurse, but my husband went to a school of nursing,” the woman said, and thereafter directed The Guardian to Graceland, a nearby private clinic.

At Graceland Clinic, a private clinic established in December 2001, a teenager, who is a “trainee nurse”, had in hand a book titled “WAEC Keypoint” and was studying for the West African Senior School Certificate Examination (WASSCE).

The clinic’s brown-and-cream walls looked tired, their paint already wearing thin. Fading charts clung to the corridor, edges curling with age. A door labelled “Bode Bode Treatment Room” led into a dim space that felt far removed from a proper medical facility. It appears that the facility is nicknamed Bode Bode, the meaning of which the reporter could not get.

Agboola Samuel Oluwole, the founder of the facility, said that he is a registered nurse who established the clinic in response to the growing demand from residents.

He explained that the facility handles childbirth, antenatal, road traffic injuries, infant welfare, vaccination, and immunisation.

“There is a general hospital here, and you know how a general hospital handles the cases of people; they are not helping to the best of their ability. We came here on demand. People called us to establish a clinic here. That was why we established this clinic in late 2001,” Oluwole stated.

When the conversation shifted to staffing, he was quick to acknowledge that the clinic runs largely with the help of auxiliary nurses.

“We have two staff members, but they are not here currently. They are off-duty, and we have trainee nurses. Our staff members are auxiliary nurses. We need their support. After training them for about three years, they go to a college of health or nursing. They attend to patients in the antenatal ward and assist during childbirth. We take these lectures regularly to prepare them for higher education,” he claimed.

This investigation also took The Guardian to Ateyese Hospital, a private facility in Odogbolu, which claims to operate 24 hours a day. Like Oluwole, Adeolu Olaniyi Olusodo, the hospital’s medical director, acknowledged that the facility employs auxiliary nurses. He, however, referred to them as “assistant nurses.”

“We give both primary and secondary healthcare services. Treatment of basic illnesses, antenatal, deliveries, in-patient treatment, and all kinds of surgeries, including caesarean section (CS). We have approximately 400-500 patients per month. We have two medical doctors, four staff nurses and assistants who help them. Of course, we utilise auxiliary nurses, whom we refer to as assistant nurses. What they do is to assist nurses in giving care to patients and assist doctors in their work,” Olusodo told The Guardian.

While the founders of other private clinics admitted to employing auxiliary nurses in their facilities, Samson Olaifa, the Founder of Omoleye Clinic and Maternity Home in Oja-Odan, told The Guardian that he does not employ auxiliary nurses in his facility because he is aware of the implications associated with that.

Olaifa said that he was a staff member of the Federal Medical Centre in Idi Aba, and later worked at the state hospital in Ijaiye before establishing his private clinic.

“We have a doctor and two nurses. We also have one Community Health Extension Worker (CHEW). We don’t train auxiliary nurses here. The government frowns at it. It was once acceptable, but it is no longer. Once they find anybody flouting the regulation, they impose hefty fines on them. The government prefers that private clinics that can’t afford to pay experienced nurses hire fresh school of nursing graduates, instead of auxiliary nurses,” said Olaifa.

The Guardian did not, however, see the doctor or nurses that he talked about in the clinic. The voice of a patient who was screaming in pain could be heard from one of the rooms in the clinic. Olaifa said that the patient was being attended to by one of the clinic’s staff.

Nursing clothed in apprenticeship

Unlike registered nurses who receive formal education in tertiary institutions, auxiliary nurses are unlicensed, informally trained health workers who assist in basic patient care. They do not meet the professional, educational, or regulatory requirements to be recognised as registered nurses or midwives.

They are trained on the job or through short, non-accredited programmes.

Auxiliary nurses are expected to perform basic tasks, such as checking vital signs, cleaning wounds, assisting with mobility, and supporting registered nurses. They are not authorised to perform clinical procedures that require professional training, such as administering certain medications, conducting deliveries, or making clinical decisions.

In Nigeria, the National Association of Nigerian Nurses and Midwives (NANNM) and the Nursing and Midwifery Council of Nigeria (NMCN) prohibit the training or employment of auxiliary nurses in clinical roles because they are not recognised by law.

The Nursing and Midwifery (Registration, etc.) Act prohibits any unlicensed person from presenting themselves as a nurse or midwife.

Section 20 of the Act reads: “Any person not duly registered under this Act who, for or in expectation of reward, practises or holds himself out to practise as such; or without reasonable excuse, takes or uses any name, title, addition or description implying that he is authorised by law to practise as a nurse or midwife, is guilty of an offence under this section”.

According to the Act, any person who employs an unregistered person as a nurse or midwife, or any registered nurse who establishes a private nursing or maternity home without complying with the provisions of the Act, is also guilty of an offence and liable to prosecution.

Hospitals and clinics that employ and train auxiliary nurses are often shut down by the Ministry of Health, and their operating licenses are withdrawn when found guilty. Despite the provision of this Act, many private clinics and hospitals still engage in this practice, reflecting a deficient regulatory framework, monitoring and evaluation shortfalls on the part of the Ministry of Health, further empowering private clinics and hospitals.

Some private clinic owners and individuals have turned auxiliary nursing into an informal apprenticeship scheme, treating it like a trade rather than a regulated medical profession. Many clinics charge trainees fees, similar to vocational apprenticeships. The arrangement benefits clinic owners, who gain cheap labour while presenting the setup as training.

These auxiliary nurses are recruited to “learn nursing” by shadowing clinic staff. They clean, dress wounds, dispense drugs, or assist with deliveries simply by watching others, not through accredited education. Sometimes, they are tasked with performing duties typically reserved for registered nurses or midwives, including administering injections, managing labour, or making clinical decisions.

Upon completing their apprenticeship, some auxiliary nurses go on to establish private clinics or local pharmacies, commonly referred to as chemists, where they administer medication and treat patients, despite not being licensed to practice medicine.

In November 2016, the Ogun State government, under the administration of Ibikunle Amosun, banned auxiliary nurses from running health facilities to curb quackery and protect citizens’ lives. This ban prohibits auxiliary nurses from operating or managing healthcare facilities in the state because they lack the required expertise and professional qualifications. The action followed a directive to re-validate and register all private health facilities, leading to the closure of several facilities for non-compliance.

A medical doctor, Tella Quadri, told The Guardian that many private hospitals employ auxiliary nurses because they can’t afford to pay registered nurses’ salaries.

“The majority of private hospitals think of how they will be able to afford the salaries of qualified nurses. That is why only a few citizens will be able to afford the medical costs of those private hospitals that make use of registered nurses, because their bill will be expensive, and many middle and low-income class Nigerians won’t be able to afford such hospitals,” said Quadri.

The actions of some auxiliary nurses have resulted in medical complications and loss of lives.

In May, Police operatives from the Ekpan Division in Uvwie Local Council of Delta State arrested a woman named Odiase Ibhade Stella, described as an auxiliary nurse, in connection with the death of 21-year-old Elizabeth Oyibode.

The alleged incident occurred at the auxiliary nurse’s chemist shop located on New Era School, off Jakpa Road in Delta State, where she reportedly administered drips and medication to Oyibode.

According to a rights-advocacy group, the auxiliary nurse claimed that Oyibode had typhoid and malaria, prescribed medication and drips, and, despite objections from Oyibode’s fiancé, the treatment proceeded.

The treatment allegedly caused paralysis of Elizabeth’s brain and body, rendering her unable to speak or interact, and three days later, she died at the Warri Central Hospital.

An auxiliary nurse was also accused of having a hand in the death of the late popular Nigerian musician Mohbad. The nurse, Feyisayo Ogedengbe, was said to have administered tetanus injections to Mohbad without a doctor’s prescription.

We are renovating PHCs, auxiliary nurses still banned – Health Commissioner

When contacted for comments, the Ogun State Commissioner for Health, Tomi Coker, said there are some PHCs across the state that were established by the community without seeking approval from the state government.

“There are PHCs that the government constructed and others that the communities decided to go and build for themselves without liaising with the government, and then they will say they have been abandoned. You can’t just be building. Building does not make the PHC. We should let the government build where there is an analysis of needs,” said Coker.

The commissioner also added that the state’s Ministry of Health is renovating PHCs across the state.

“We are renovating over seven PHCs in Ipokia LGA. We have spent millions in renovating even in rural areas,” she said.

The commissioner listed the PHCs in Ohunbe, Idofio, Igbogila, Ojaodan, Igboho, Okeila, Ajilete, Ojuelegba, Iwoye, Afon, Idofia, Ketu, Ajegunle, Idiiroko, Ifoyinytedo and Tube as some of the PHCs the state’s Ministry of Health has renovated.

Coker also told The Guardian that the state’s ministry of health frowns on private clinics operating with auxiliary nurses, adding that the ministry has closed down many PHCs flouting the no-auxiliary-nurse rule.

“They are still banned. We have sanctioned private clinics. There is a whole team in the Ministry of Health that goes out every week monitoring those people.”

She also promised to sanction the private clinics that employ and train the auxiliary nurses, as exposed in this report.

“If you find them, give me the list of places that you went to. We will shut them down because that is how they kill people,” said Coker.

Quadri, a medical doctor, believes auxiliary nurses should be flushed out of the Nigerian healthcare system.

According to him, the best way to achieve this is through adequate enforcement and increasing the number of students admitted into colleges of nursing and health nationwide.

“The government can curb this auxiliary nurse practice by enforcing all private hospitals to employ only qualified and registered nurses, and by admitting more students into nursing schools and colleges of health,” Quadri suggested.

This report was done with the support of the International Centre for Investigative Reporting, ICIR.