A tour of primary healthcare centres in Ogun West and Ogun East senatorial districts reveals shocking scenes of lack and negligence capable of costing human lives. OLAYIDE SOAGA found out that the Basic Health Care Provision Fund (BHCPF)-funded facilities lacked amenities, manpower and logistics to effectively discharge their functions despite drawing funds to make primary healthcare truly accessible and affordable for Nigerians living in rural areas.

One quiet Sunday morning in October, Ogunnowo Abiodun sat alone in the female ward of Ogbere Primary Health Centre (PHC), a modest facility tucked away in Ijebu East Local Council of Ogun State.

Dark-skinned and plump, with a calm composure, the woman in her early 40s worked as a health attendant at the centre, one of the facilities benefiting from the Federal Government’s Basic Health Care Provision Fund (BHCPF).

To her left, the male ward lay empty. The other rooms were locked, the facility’s surroundings swallowed by silence except for the sound of a motorcycle from across the street.

Abiodun was the only health worker on duty that day in the unfenced compound, a place meant to serve thousands but is now eerily still. Across from the plastic chair where she sat, a 16-inch television flickered weakly, its low hum also breaking the midday quiet. Outside, an abandoned tricycle ambulance stood motionless – a stark reminder of promises once made to bring health care closer to the people.

The PHC’s Officer-in-Charge, Nurse Adeyeri, was not available. “The Officer in Charge is taking a course in another community, so she is not available. The other staff member) is currently off duty. So I am the only one here,” Abiodun said.

When The Guardian inquired about the condition of the facility and its staff strength, she smiled and insisted that everything was fine. “We have no problems here,” she said.

Then, almost as an afterthought, she mentioned that the borehole, which was the only source of water for the centre, had been damaged for months.

It was a small confession that hinted at a deeper truth; beneath the calm surface of Ogbere PHC, the cracks were already showing despite being a beneficiary of the BHCPF.

“The only issue we have here is the bad borehole. It got damaged recently, so we don’t have water. We always have to fetch water outside. That is the reason I have not had my bath by this time,” she added. She also told The Guardian that the facility had no staff quarters.

But what Abiodun did not understand was that a functioning borehole and the absence of a staff quarters were only two of many things that the BHCPF-funded facility lacked.

The Ogbere PHC fell short of several minimum standards outlined in the National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA) guidelines, which list essential requirements that every PHC must meet to deliver quality healthcare – from qualified personnel and medical equipment, to reliable electricity, water supply, and functional vehicles for emergencies.

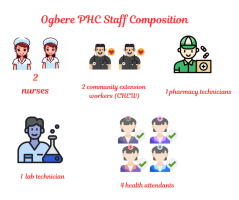

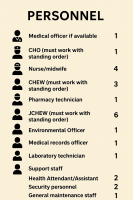

The Ogbere health attendant told The Guardian that the PHC has two nurses, two Community Health Extension Workers (CHEWs), one pharmacy technician, one lab technician, and four health attendants, falling short of the basic minimum requirement of one medical officer, one Community Health Officer (CHO) (must work with a standing order), four nurse/midwives, and three CHEWs (must work with a standing order). One Pharmacy technician, six Junior Community Health Extension Workers (JCHEWs) (must work with standing orders), one Environmental Officer, one Medical Records Officer, one Laboratory Technician, two Health Attendants/Assistants, and two security personnel stipulated by the NPHCDA.

About the BHCPF

ESTABLISHED under Section 11 of Nigeria’s National Health Act of 2014, the BHCPF represents one of the country’s efforts to achieve universal health coverage and strengthen the Primary Health Care (PHC) system across the country.

The law was signed by former President Goodluck Jonathan, but its implementation began in 2019 under President Muhammadu Buhari, following years of planning and advocacy by the Federal Ministry of Health and development partners.

Among other things, the BHCPF was created to address the chronic underfunding and weak infrastructure that have virtually crippled Nigeria’s health system, particularly at the grassroots level. Its goal is simple but crucial – to ensure that every Nigerian, especially the poor and vulnerable, can access basic health services without facing financial hardship.

Funded by at least one per cent of the Consolidated Revenue Fund (CRF), the BHCPF serves as a sustainable financing mechanism that channels resources directly to frontline health facilities. The fund is disbursed through key agencies: the NPHCDA for essential drugs and facility upgrades, the National Health Insurance Authority (NHIA) for covering the basic minimum package of services, and the Federal Ministry of Health (FMoH) for emergency medical treatment.

Through the fund, thousands of PHCs now receive direct financial support to maintain operations, procure medicines, and deliver maternal and child health services. Ward Development Committees (WDCs) also play a role in monitoring the expenditure of funds at the community level.

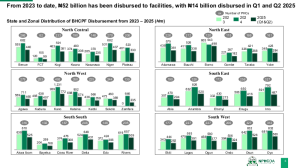

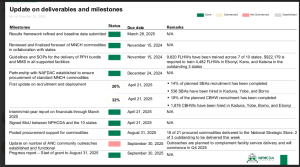

According to the latest NPHCDA Gateway Updates presented by the Executive Director of the agency, Dr Muyiwa Aina, N52 billion has been disbursed to PHCs by the agency between 2023 and October 2025. It was also revealed that N14 billion was disbursed to facilities between the first and second quarters of 2025.

Ogun State received N458 million in 2023, N580 million in 2024 and 377 million between the first and second quarters of 2025. These funds are distributed between the 227 BHPCF facilities in the state.

Despite this funding, some PHCs in Ogun State that are beneficiaries of the funds still face similar challenges to those that are not recipients of the scheme. The NPCHDA executive director further noted that 18 per cent of the planned Community-Based Health Worker (CBHW) recruitment has been completed, adding that 1,878 CBHWs have been hired in Kaduna, Yobe, Borno, and Ebonyi states.

When The Guardian visited BHCPF-funded PHCs across Oja Odan in Yewa North, Ipokia and Ado-Odo local councils in Ogun West Senatorial District, and Odogbolu and Ijebu-East local councils in Ogun East Senatorial District, it was discovered that many of them lacked the minimum requirement for health staff, while others did not have functional boreholes and vehicles for emergencies, making them no different from PHCs not funded by BHCPF.

Similar unpalatable tales elsewhere

AT the Alaga Primary Health Centre in Ipokia Local Council, where four female staff members of the facility sat outside the fenced building, the Officer-in-Charge, Silifat Ogunjobi, revealed that the PHC has a functioning borehole that is solar-powered.

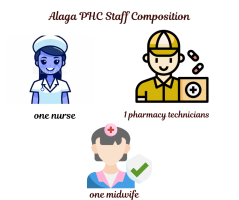

When The Guardian inquired about staff strength, Ogunjobi simply stated that the PHC had sufficient personnel. The “enough hands,” Ogunjobi talked about, turned out to be one nurse, one midwife and a pharmacy technician, falling short of the required 24 staff stipulated by the NPCHDA guidelines.

The Oja Odan Rural Health Centre was undergoing renovations when The Guardian visited a few weeks back. A health worker, who requested anonymity, revealed that the renovation has been ongoing for over three months.

While a group of women sat outside undergoing registration, artisans were at work inside the facility. Buckets of paint, different sizes of wood and a saw littered the ground. The interior reeked of paint and toxic chemicals, yet the Oja Odan health worker assured that the PHC was still receiving and attending to patients.

When probed further about the staff strength and the availability of basic amenities at the PHC, the health worker wore a proud smile and said confidently, “We have everything. Drugs, beds, solar power and water. We have enough staff. There is no problem here.

To her, the facility had more than enough health workers to serve the thousands of residents who rely on it. But checks with the NPHCDA tell a different story – the centre falls short of the minimum staffing requirements expected of a standard primary health care facility.

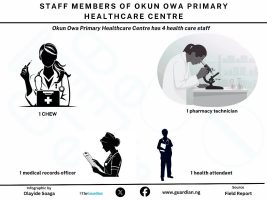

The Okun Owa Health Centre in Odogbolu Local Council, Ogun East Senatorial District, has only one CHO, three CHEWs, one pharmacy technician, one medical records officer, one health attendant, and two environmental officers. The PHC also lacks an ambulance for emergencies.

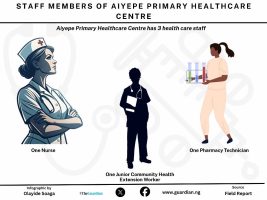

At Aiyepe, another PHC in Odogbolu Local Council, Deborah Onasegun, a staff member, told our correspondent that the PHC has one nurse, one pharmacy technician, one junior CHEW, one health attendant and one security personnel.

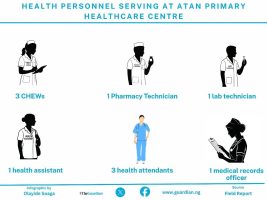

At Atan MPHC, a staff member told our correspondent that the facility staff comprises three CHEWs, one pharmacy technician, one laboratory technician, one health assistant, three health attendants, and a medical records officer. She also mentioned that the PHC lacked solar power but has an operational ambulance.

PHCs operating without nurses/midwives, ambulance

OUT of the six BHCPF-funded PHCs that The Guardian visited across the Ogun East and Ogun West Senatorial Districts, only three – Oja Odan, Alaga, and Atan have serviceable ambulances for emergencies, while the facilities at Ogbere, Aiyepe, and Okun Owa lack functional ambulances.

Ambulances are a key component of prehospital emergency care, as highlighted in the WHO prehospital toolkit.

According to the WHO, they are essential in saving lives and preventing medical complications.

“Timely care and rapid transport save lives, reduce disability and improve long-term outcomes. Prehospital emergency care is a vital component of the healthcare system. Strengthening prehospital care can help address a wide range of conditions across the life course, including injury, complications of pregnancy, exacerbations of non-communicable diseases, acute infections and sepsis.”

The WHO also notes that despite their importance, prehospital systems such as ambulance services are often underdeveloped, a situation this investigation confirms. The organisation warns that weak or poorly coordinated emergency systems can lead to negative health outcomes.

“Many health systems lack an enabling regulatory framework, coordination mechanisms, trained personnel, and adequate equipment and infrastructure, leading to delayed or inadequate emergency care and poor outcomes.”

The NPCHDA also stipulates ambulance vehicles as part of the minimum requirements for PHCs in Nigeria. All the PHCs visited were operating with fewer nurses/midwives than the minimum required for PHCs recommended by the NPCHDA.

According to the body, PHCs should have a minimum of four nurses/midwives. The Guardian’s investigation, however, revealed otherwise. At Ogbere, Abiodun stated that the PHC has two nurses but no midwife. Alaga PHC has one nurse and no midwife. Aiyepe has one nurse, while Atan has two nurses, but one of them doubles as a midwife. Okun Owa PHC, however, does not have either a nurse or a midwife.

Same reality in PHCs not funded by BHCPF

FINDINGS by The Guardian showed that there is not much difference between the PHCs that are beneficiaries of BHCPF and their counterparts that are not funded by BHCPF in Ogun State, in terms of meeting the minimum staff requirement. Our correspondent visited two PHCs in the Ogun West and Ogun East Senatorial Districts, which are not beneficiaries of the BHCPF.

At the PHC in Agbon Ojodu, a community in the Yewa North Local Council, three people, consisting of a dark-skinned woman, a light-skinned woman with tribal marks on both cheeks, and a man who appeared to be in his 40s, sat on a wooden bench inside the facility. The Officer-in-Charge was unavailable.

A conversation with them revealed that the PHC had been renovated earlier in the year. In previous years, the newly renovated PHC was in ruins. An investigation published by FIJ in 2024 revealed that the PHC had a damaged ceiling that leaked whenever it rained, allowing bats to fly inside in broad daylight unperturbed.

The PHC, which is the only operational one serving three communities, underwent a renovation exercise at the behest of Senator Solomon Olamilekan Adeola, representing Ogun West. For a recently renovated PHC, the condition of the facility suggests that the renovation was incomplete or not properly done. The Guardian was informed that the PHC lacks medicines and water, and has no restroom, forcing patients to use an abandoned building within the premises to ease themselves.

Ikosa Community Health Centre in Odogbolu, another one not funded by BHCPF, was also in a similar condition when The Guardian visited. A health assistant at the facility, who introduced herself as Mrs Sobamowo, stated that the PHC has no nurses, no midwives, and only relies on two CHEWs. She added that they have no running water, solar electricity, a toilet and their roof leaks whenever it rains.

Shortage of health workers spikes burnout, hobbles knowledge transfer

FROM doctors to nurses and other healthcare workers, the country’s population of medical professionals is experiencing a significant decline, largely due to brain drain. Nigeria has a density of only 1.83 skilled health workers per 1,000 people, which falls far short of the WHO’s recommendation of 4.45 per 1,000 people.

Health workers have protested unfavourable working conditions and meagre pay for years. Without the government’s positive response to their demands, many are fleeing in search of greener pastures, causing a shortage. As a result of this shortage, health workers are experiencing burnout, and patients are spending long hours waiting at medical centres.

Dr Joyce Foluke Olaniyi-George, a public health specialist with over two decades of experience in the field, stated that the shortage of health workers is not only causing burnout among health workers and long waiting hours for patients, but is also adversely affecting the transfer of knowledge.

She explained that it is essential to have a sufficient number of senior professionals in PHCs, who can pass on the knowledge that they have acquired over the years to junior staff.

“You can imagine a PHC with maybe one senior person and a fresh graduate. Nothing is going to get done there because the person is about to retire and is tidying things up to get out. We will find out that there will be a lot of frustration on the part of the staff, which could be transferred to the patients, and poor treatment meted out to patients when they come in, as a result of the poor motivation.“

“This creates a vicious cycle that would give rise to poorly trained health workers, nurses, or community health extension workers who would also be poorly motivated. Ultimately, the system suffers as a result. If they have the opportunity, they will likely consider exiting the system. Whereas you would have loved them to remain, especially in those hard-to-reach communities and areas that they actually come from.

“So, you have a situation whereby a village, town or community is producing community health extension workers or nurses who would not stay in that community. And the question now is, ‘Who else will come to take care of that community?’

Where health becomes inaccessible

Some months back, 46-year-old Funmilayo Obasa was hitching a ride home alongside two other passengers on a commercial motorcycle when suddenly the bike lurched, tipped and finally crashed, leaving Obasa with a sprained right elbow, a fractured right shoulder, and a cut on a toe. The pain from these injuries was not her only battle.

She was rushed to the Ijebu Ode General Hospital for treatment. Upon arriving at the hospital, Obasa discovered that the pain was only one layer of the ordeal she had to face. As a hearing-impaired woman, she searched the room for someone who could understand her expressions, the pains she felt in her hands, but she found none. No sign language interpreter was available.

The attending health worker could not understand Obasa’s gestures and was unable to hear what was being said. The scene was painfully familiar. In public offices, in banking halls, even during past hospital visits, Obasa had been forced to bridge communication gaps on her own.

Amid a medical emergency, she was forced to fall back on the tools she had learned to depend on – reading lips and scribbling words on paper. It was a routine she knew too well.

When asked if she received adequate care on that day, Obasa responded: “I was fairly attended to.” According to her, it was better than other past experiences when she had to escalate her tone to get proper care.

“I have noticed that when I am calm and polite, my concerns seem to get overlooked, but when I get frustrated and speak up, things start to happen. It is concerning that I have to escalate my tone to get proper care,” Obasa told The Guardian via text message.

PWDs’ perennial burden of absence of inclusivity

OBASA is not alone; many Persons With Disabilities (PWDs) in Nigeria still struggle to access basic amenities such as education, banking services, and healthcare, and face steep barriers when trying to join the labour force. For years, they have spoken out against discrimination and appealed for public spaces that reflect their needs.

In response to these long-standing concerns, the Federal Government mandated the use of ramps and other accessibility features in 2018, when the Discrimination Against Persons with Disabilities (Prohibition) Act was signed into law on January 23, 2019.

The law requires all public buildings to be accessible to everyone, with a compliance window of five years.

Many states have adopted the provisions of the PWD Act by implementing it within their jurisdictions and replicating its key provisions. The PWD Act for states like Lagos and Sokoto, for instance, stipulates that arrangements should be made for individuals who cannot communicate normally, including those with speaking and hearing impairments.

In Ogun, however, the state’s disability law, which was signed into law by a former Governor of the state, Ibikunle Amosun, in 2017, has yet to be implemented.

Although some public institutions have since installed ramps, many others remain inaccessible. And for a community with diverse needs, structural adjustments often stop at the most visible solutions. Most public buildings and organisations cater only to people with physical disabilities who use wheelchairs, while excluding those with sensory disabilities – such as people with visual, speech, or hearing impairments, like Obasa – who require entirely different forms of accessibility assistance.

PHCs operate with ramps, but no sign-language interpreter

THE General Hospital, which Obasa visited, is not the only healthcare facility without sign language interpreters. Primary Health Centres (PHCs) are often the first point of contact for many Nigerians seeking accessible and affordable healthcare services in communities, particularly in rural and underserved areas, and they also lack sign language interpreters.

Our correspondent noticed that the PHCs in Ogbere, Alaga, Atan, and Oja Odan have ramps for people with physical disabilities. The lead for the Ogun State Joint National Association of Persons with Disabilities (Deaf Cluster), Femi Adeosun, however, noted that the availability of ramps does not stipulate full access.

“Ramps are like motorways; they do not stipulate full access. After the wheelchair-bound patient enters the building, what transpires thereafter will determine the accessibility,” said Adeosun.

From conversations with healthcare workers during The Guardian’s visits to six PHCs, which are beneficiaries of the BHCPF, across Ogun East and Ogun West Senatorial Districts, namely Ogbere, Oja Odan, Alaga, Atan, Aiyepe, and Okun-owa PHCs, it was learnt that they all lack sign-language interpreters or braille for visually impaired people.

The PHCs in Aiyepe and OkunOwa are, however, inaccessible to people with all forms of disabilities. It has no ramp and no sign language interpreter.

The BHCPF strives to ensure that every Nigerian, especially the poor and vulnerable, can access basic health services without facing financial hardship. But even PHCs that are beneficiaries of BHCPF shut people with disabilities out of accessing healthcare.

Inside the smaller minority

INDIVIDUALS with sensory disabilities are a minority within the already marginalised PWD population. Without sign-language interpreters in PHCs and most medical facilities, their needs are often overlooked. This leaves patients like Obasa doubly marginalised – part of a minority group, yet pushed further to the edges as a sub-category whose access to care is routinely ignored.

This was echoed by Adeosun.

“The deaf are the most marginalised because everything begins with communication, and here we are with no sign language interpreters in hospitals and PHCs. The absence of sign language interpreters means no inclusion of the deaf. So, they are seen as a minority due to the communication barrier.

Vincent Akintola, a resident of Ogun State with hearing impairment, told The Guardian that the lack of sign language interpreters in medical facilities such as PHCs is not the challenge people with hearing impairments face when they go to access care. He told The Guardian that health workers often treat them condescendingly.

“Discrimination is still standing to manipulate our rights to benefit from PHCs. If deaf people go there, once people like nurses know that we are deaf, they see us as animals and would tell us to sit and wait until they finish attending to people who can hear before attending to us. Sometimes, they may charge us exorbitant amounts of money.

Due to the non-availability of sign language interpreters in PHCs and other healthcare facilities, people with hearing impairments often have to bring their children, relatives, or friends to these facilities to bridge the communication gap between themselves and healthcare workers. In facilities where interpreters are unavailable, they must act as their own sign language interpreters. Akintola told The Guardian that, however, children of parents who are hearing impaired are also discriminated against in such spaces.

“Our children are also facing embarrassment in PHCs. We only keep our calm whenever insults are hurled at us and harassment challenges our rights,” said Akintola.

In September, Akintola, a school teacher, visited the PHC at OPIC Okelowo to receive free eyeglasses distributed by the National Orientation Agency. The teacher went in the company of three other PWDs, one of whom was physically challenged.

At the PHC, there was no sign language interpreter; the physically challenged individual served as his own sign language interpreter to facilitate seamless communication between him and the attending staff. He added that if the physically challenged acquaintance was not available, he would have resorted to communicating with the attending staff in writing.

According to the hearing impaired cluster of the JONAPWD in Ogun State, people with hearing impairment in the state are subjected to such a condition because of the absence of a working law to promote the rights of PWDs.

“Accessibility of PWD in healthcare is not well understood in our society, particularly in Ogun State, because there has been no awareness, as there is no working law. We are still pushing for the implementation of the disability bill.”

Non-availability of sign language interpreters in PHCs pushes PWDs to self-medication

AS healthcare remains inaccessible for people with hearing impairment in PHCs, they are forced to embrace self-medication as an alternative.

According to the WHO, self-medication involves the use of medicinal products by consumers to treat self-diagnosed disorders or symptoms, or the intermittent or continued use of medication prescribed by a physician for chronic or recurrent diseases or symptoms.

People self-medicate for several reasons, such as lack of access to healthcare or unaffordability of quality healthcare. In some areas, medical services are limited, expensive, or inaccessible due to distance. People self-medicate because seeing a doctor is inconvenient or unaffordable. Self-medication is often seen as a cheaper alternative for many. People may avoid costs such as doctor’s consultations, diagnostic tests, or transportation to a health centre.

A PWD advocate, Yinka Olaito, attributed the prevalence of self-medication among people with hearing impairment to the absence of medical professionals with knowledge of sign language in PHCs and hospitals.

“It is very clear that the government is not taking significant steps in ensuring access to health is a reality. To date, our medical officers still have language limitations in their bids to communicate with people who are hard of hearing and those with just a minor hearing impairment,” said Olaito.

“All these are discouraging reasons why many do not bother to attend regular health institutions. This must stop if we truly believe every life counts.”

‘You have to prove there is a need for interpreters’

WHEN The Guardian informed Ogun State’s Commissioner for Health, Dr Oluwatomi Coker, that the PHCs visited lacked sign language interpreters for people with hearing impairment, she said The Guardian must prove that there is a need for sign language interpreters in those PHCs.

“You have to define a need. If I were you, the first thing I would find out is the number of people who visited that PHC with hearing impairment. So, you have to prove that there is a need for it. That is journalism. It is like me coming to your house to say, ‘Why can’t you eat this in your house? You don’t have caviar in your house?’ The commissioner asked.

Coker added that providing sign language interpreters in every PHC may not be feasible because some PHCs record a low number of turnouts, adding that she conducts inspections across communities and has never met a person with hearing impairment in the PHCs that she has inspected.

“I have never met a deaf person or a blind person in any of those PHCs. At least we know of people who are in wheelchairs. People don’t use the facilities. So we are just paying salaries, and nobody is attending the PHCs. Tell the community residents to use the facilities. If they do so, we will put more services there. But if they don’t use it, what are we putting those services there for?”

According to her, a solution to making PHCs accessible for people with hearing impairments will be training staff members in sign language to enable them to become effective in communicating with individuals who are deaf or hard of hearing.

“If you want to advocate for PWDs, start with federal policies. Start with the MPCHDA that trains our staff. Maybe they should train the staff in sign language. We are going to look into training our staff in sign language, not that we are going to employ people that we are waiting for,” she added.

But the delay in providing a solution is costly.

Obasa, who survived a road crash in 2024, said she is working to raise awareness about inclusion by training people without hearing impairments in sign language to bridge the communication gap between the two groups.

“This year, there were two deaths among the deaf people, due to ignorance and negligence, and partly because of the unavailability of sign language interpreters in healthcare facilities. I am working to raise awareness and lobby for inclusion by training hearing counterparts in sign language and partnering with medical groups to improve healthcare access for the deaf community,” said Obasa.

This report was done with the support of the International Centre for Investigative Reporting, ICIR.