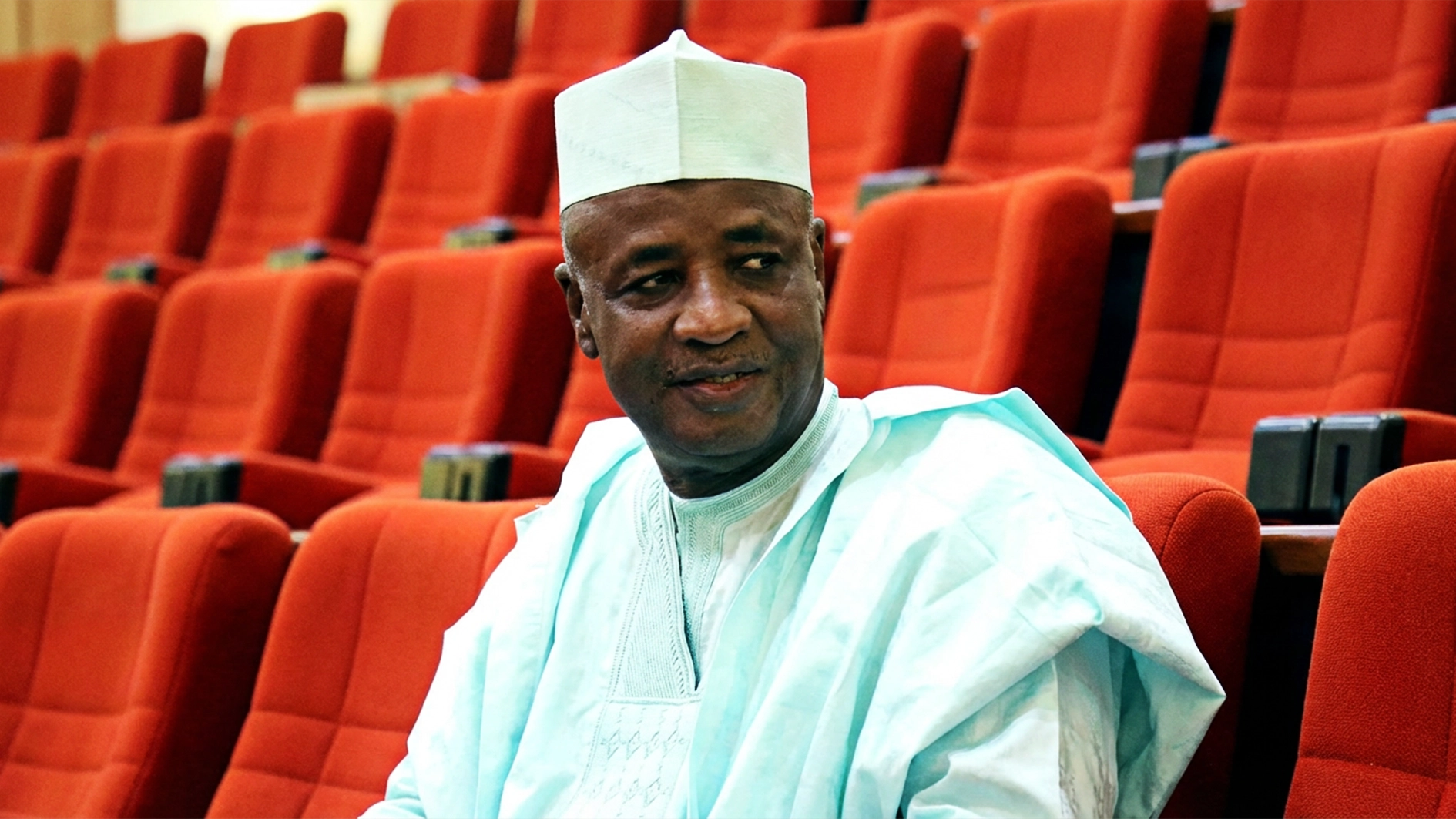

At a scientific event in June 2024, I had the opportunity to sit down with Dr. Idowu Peter Shileayo Adebayo, a general practitioner and an epidemiologist with expertise in infectious diseases and public health surveillance. With over a decade of clinical and public health experience spanning Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, and the United States, Dr. Adebayo shared critical insights into the rising threats of infectious diseases, the disparities in healthcare response, and the policy recommendations that could bridge the gap between both nations.

The United States and Nigeria face unique yet interconnected challenges in combating infectious diseases. While the U.S. battles increasing antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and emerging zoonotic threats, Nigeria struggles with inadequate disease surveillance, vaccine hesitancy, and infrastructural deficits. According to the CDC, the U.S. reported over 2.8 million cases of antibiotic-resistant infections in 2023 alone, leading to 35,000 deaths annually. Meanwhile, Nigeria continues to grapple with high mortality rates from preventable infectious diseases, with the World Health Organization (WHO) estimating that over 200,000 deaths in 2023 were linked to malaria, tuberculosis, and HIV/AIDS.

Dr. Adebayo, who currently serves as an epidemiologist at the Mississippi State Department of Health, emphasized that infectious diseases know no borders. The rise of global travel, climate change, and evolving pathogens mean that both Nigeria and the U.S. must invest in resilient healthcare infrastructures to prevent outbreaks from spiraling out of control.

HIV remains a pressing public health crisis in both countries, albeit with different epidemiological dynamics. In the U.S., HIV infections have declined due to antiretroviral therapy (ART) accessibility and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). However, disparities persist—Black and Latino populations account for over 40% of new infections despite making up a smaller fraction of the total population. In Nigeria, 1.9 million people live with HIV, and only 1.6 million are on treatment.

Stigma, cultural barriers, and inconsistent funding for HIV programs hinder progress. Dr. Adebayo, who manages HIV surveillance data in Mississippi, explained that one of the biggest issues is care retention. Many patients drop out of treatment due to financial or social constraints, making disease monitoring a significant challenge.

A rising concern in both the U.S. and Nigeria is antimicrobial resistance (AMR), which renders antibiotics ineffective against previously treatable infections.

The CDC has classified AMR as one of the top public health threats, with drug-resistant infections causing over 35,000 deaths annually in the U.S. In Nigeria, unregulated antibiotic use and poor healthcare infrastructure have accelerated AMR. A 2023 study found that more than 70% of bacterial infections in Nigerian hospitals are resistant to first-line antibiotics. Without urgent intervention, simple infections will become untreatable, leading to a potential health catastrophe, Dr. Adebayo warned.

The resurgence of measles, polio, and other preventable diseases has highlighted the consequences of vaccine hesitancy and misinformation. In the U.S., measles cases surged by over 30% in 2023, largely due to vaccine skepticism among certain communities. Nigeria, while making strides in polio eradication, still battles low immunization coverage, particularly in northern regions where insurgency and insecurity prevent vaccine distribution. We need to shift our focus to community-based education and combat vaccine misinformation aggressively, Dr. Adebayo urged.

To mitigate the threats posed by infectious diseases, Dr. Adebayo proposed a three-pronged approach. First, disease surveillance systems must be strengthened.

The U.S. should expand genomic surveillance programs to track emerging variants of infectious diseases, while Nigeria must invest in real-time disease monitoring and laboratory infrastructure to enable early outbreak detection. Second, public-private partnerships in healthcare should be expanded. Governments in both countries should collaborate with private-sector stakeholders to ensure a sustainable supply of medications, vaccines, and diagnostic tools. Nigeria, in particular, should increase domestic vaccine production to reduce reliance on foreign donors. Third, community engagement and education must be prioritized. Health literacy is a powerful tool against infectious diseases. Both nations need grassroots campaigns to educate communities on preventive measures, proper antibiotic use, and the benefits of vaccination.

As global health threats evolve, Nigeria and the U.S. must adopt proactive measures to safeguard public health. Whether through policy reform, improved healthcare infrastructure, or strengthened international collaboration, the future of disease control depends on data-driven decision-making and public engagement. We cannot afford to be reactive anymore. The next pandemic is not a question of ‘if’ but ‘when.’ Investing in disease prevention now will save millions of lives in the future, Dr. Adebayo concluded.