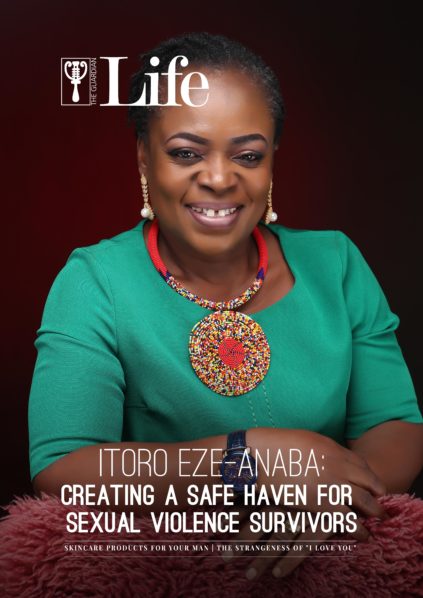

In 2003, Itoro Eze-Anaba was working with an organisation, Legal Defence and Assistance Project, when she was approached by a young married lady, a victim of domestic violence, who narrated her ordeal to her and sought her help to reconcile her back with her husband.

Her effort to help the lady showed a lapse that had gone unnoticed for years: Nigeria had no law offering protection to victims of domestic violence.

Stunned by this discovery, she drafted the domestic violence bill and saw herself travel to 12 states across Nigeria to campaign for state governments and lawmakers to sign the bill into law.

During her campaign, she encountered another reality. A young girl she met in Lagos, one of the states, told her about her father who had been sexually molesting her since the age of 11. Traumatised, the young girl reached out to her source of hope, her religious leader “who concluded that she was not telling the truth.” It was during her desperate search for help that she met Itoro.

Filled with even more determination, Itoro’s resolve to establish Mirabel centre, the first domestic and sexual assault centre in Nigeria, came after attending a seminar on sexual violence in Manchester, UK. But the domestic and sexual violence conversation was relatively new in Nigeria. Those close to her didn’t understand why her focus would be on a topic addressed in secret.

When we started in 2003, a lot of people, even the policymakers, discouraged me, some said why not HIV? Then it was very topical. Some said, ‘What is in this that you want to focus on it?’ ‘How about cancer?’

At a point, it was of no cost to the government, all we wanted was a memorandum of understanding between us and the Lagos state teaching hospital, and it was so difficult to get it. They just couldn’t understand why I was insistent on domestic violence but it was all part of the experience so we can track and see how we’ve thrived.’

It took me about 10 years to be able to raise funds to open Mirabel centre and the first grant we got to open the centre was from the Justice of All (J4A) Programme funded by the UK government’s Department of International Development. They funded the centre the first three years before others stepped in.

Since the establishment of Mirabel centre in 2013, the centre has helped survivors in thousands, providing free services, sometimes beyond the survivor’s initial needs. “Besides the free services that we offer, we have people that need to pay their house rents, hospital bills, school fees, and there are some that are pregnant.”

Then in 2017, the hashtag #METOO not only became a hashtag but a conversation starter in several circles (including #ArewaToo and #ChurchToo in its later stage), and the MeToo movement supported Itoro’s business. Not only were Nigerians becoming painfully aware of sexual violence and its implication, but it also opened up Nigerians to the reality on the need to expose and depurate the rape-enabled environment.

As the movement spread in circles, so did Itoro’s message become easily adopted. Yet, of all the arguments and unlearning that Nigerians have had to embrace, the blame on the survivor’s dressing is one that is refusing to die off.

We will be 7 in a week, the youngest client to come for treatment is a 3-month-old baby and the oldest, 70 so ‘what was the 3-month-old baby wearing?’ ‘What was the attraction?’

We need to understand that rape is not about sex, rape is about power. It is a matter of exercising control, showing that ‘yes, we can do this and get away with it.’

We also need to learn that rape is a crime. People think it is just stats and get on with their lives saying, ‘God will judge.’ They don’t realise that rape does something to the survivor, it takes away something from the survivor. It takes away your humanity, it touches the core such that you are left feeling empty and shallow. That 5 minutes leaves lifelong scars on the survivors.

[ad]

While grappling with this education, COVID19 struck. The advent of the COVID19 also saw an unusual reportage of sexual violence cases around the world.

In France, the Junior Minister for Gender Equality, Marlène Schiappa, reported that there were five times more reports of abuse and a spike in cyberbullying with sexual undertones during the lockdown so that the government paid hotels to accommodate victims of domestic and sexual abuse and opened about 20 centres besides the donation of one million euro ($1.1 million) to anti-domestic abuse organisations.

In Russia, the case was similar as hotels were used as domestic and sexual abuse centres and shelters. This narrative is no different from China.

Itoro opines that a major reason why Nigeria saw an increase is its reportage.

Before COVID19, rape was a pandemic. When we started in 2013, we used to see on the average 20 people a month, then sometime from 2015, the number started to increase to the extent that before the pandemic, we started seeing 85 people a month, sometimes a 100. And it was becoming routine to see a 100 or more. The only thing is that the reportage increased during COVID19 so people were encouraged to speak out.

She also noted that due to the restriction on movement, face-to-face interactions were reduced to a bare minimum while social media increased tremendously.

With the social media calls also came heavy leaning on social media to call out alleged perpetrators. Calling out alleged perpetrators sometimes proved to bring to account the actions of the accused. Some survivors also saw this as a medium to finally speak out/ say their truth. But is social justice a win for these survivors?

Itoro argues that for a lot of survivors, what they need to hear is, ‘I believe you.’

Telling their stories is a way of healing, so we cannot deny them that. On the other hand, speaking out comes with the fast life especially if it happened long ago and your perpetrator is now a popular figure. People begin to think, ‘Oh! You want to pull this person down.’ We’ve seen survivors that made a report and they were laughing throughout. It doesn’t mean that is not it is not true, that is the way they are coping with the trauma.

“Survivors cope in different ways. And they can remember things at different times, what they remember today may not be what they remember tomorrow. We need to understand that the story is not ours, the story belongs to the survivor and the survivor will only speak out when he/she is willing, ready and able so you cannot give the survivor a timeline on when the survivor should speak out.

Silencing The Victim

For Itoro and her team at Mirabel Centre, sometimes, the public is not the only one who drown out the voices of those speaking out, perpetrators have also attempted to bury the case.

Although they have been quite fortunate with diluting the power the perpetrator has on survivors’ cases, Itoro recalls a particular incident involving a particular Nigerian artiste.

“This involved a popular musician in the country. The survivor came and wanted to speak with me. I don’t know how the perpetrator got to know she was there and called her to threaten her and inform her that I was not in the country at the time. So that was a little uncomfortable for me.”

According to Itoro, bribery attempts are more common. To prevent this from happening, doctors and survivors’ names are not written in their documents.

To help victims, Itoro says that it is necessary to engage the police. This is because the survivor’s first point of contact with the legal system is the police.

In light of this, she stresses the need for domestic violence and sexual assault unit in police stations across the country.

If the police can set up a unit based on gender-based violence, then we’d know that the government is serious about putting an end to this scourge.

Interestingly, Itoro notes that religious leaders have responded favourably to her organisation. Indeed, the past three years has seen the flow of male survivors, most of whom were on referral from religious leaders.

Hope For A Better Future

Itoro is happy that since the establishment of the Mirabel Centre, Nigeria has seen the rise of domestic violence and sexual assault centres.

There are over 20 centres in Nigeria; three of which are managed by Itoro. Nana Khadija centre, Sokoto which Itoro and her team manages have attended to over 50 survivors since its establishment two months ago. It is her desire that each state would have at least three centres.

As someone who deals with trauma every other day, it must be hard to escape that reality. Itoro admits that despite this reality, she tries to keep herself happy by reading and watching a lot of football.

She adds that she and her team take “the first Friday of the month as our day off besides the retreats and day-outs that we have.”

Also, they understand that even the counsellor needs a counsellor. As such, they have counsellors that counsel the staff to take care of the mental and physical health.

[ad unit=2]