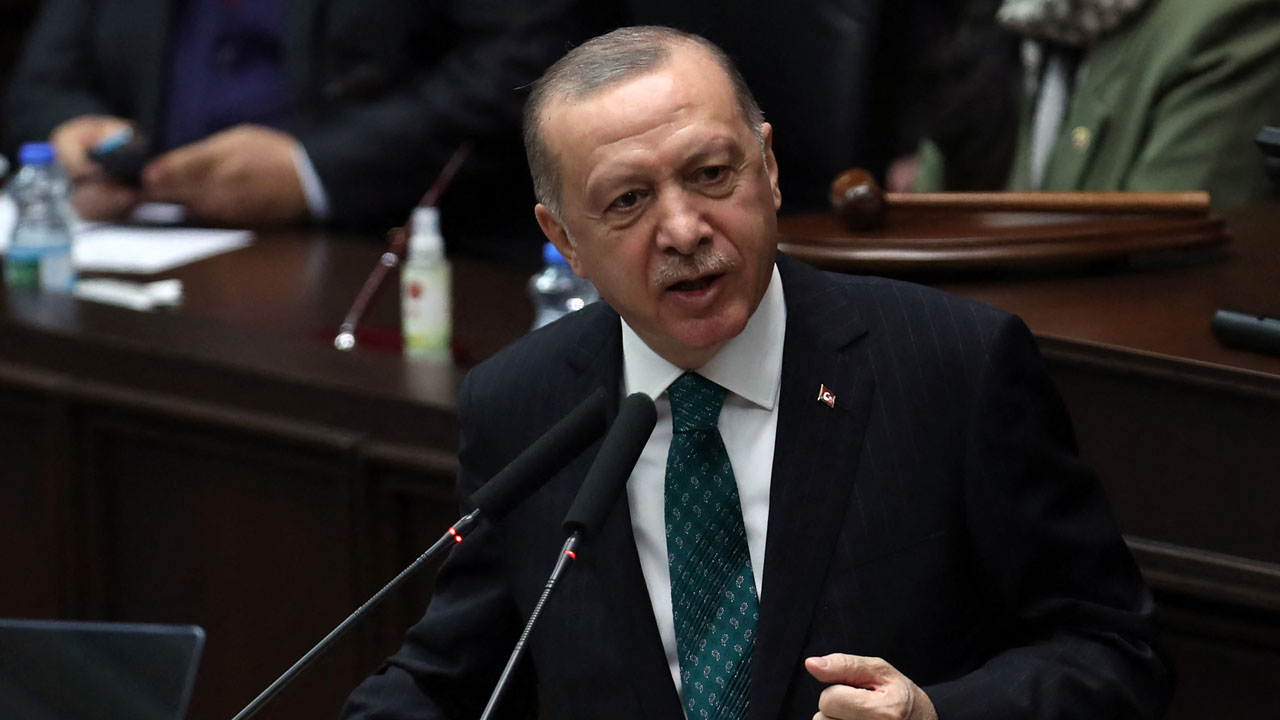

Four years after Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan assumed sweeping powers, he has wrong-footed his opponents once again by calling for a new constitution, sparking accusations of trying to set up a diversion from the country’s woes.

Taking seemingly everyone off guard, Erdogan mentioned early last week during one of his near-daily speeches that “it may be time for Turkey to reopen the debate about a new constitution”.

The timing aroused immediate suspicions over the intentions of a man who has been at the apex of Turkish political life since 2003, first as prime minister and since 2014 as president.

The 66-year-old Turkish leader is facing a sudden burst of student protests, an economy that was under strain even before the coronavirus pandemic struck last year, and polls showing a melting support base.

The current constitution was changed in a controversial 2017 referendum which created an executive presidency.

It went into force barely a year later when Erdogan won re-election, with the amendments allowing him to consolidate his power.

Since then the only politicians demanding constitutional changes have been members of the opposition, all calling for a return to the previous parliamentary democracy.

Few think this is what Erdogan has in mind.

“This is only an attempt to change the agenda so that the economy, the pandemic, farmers’ concerns, traders’ worries and rights violations aren’t discussed,” Idris Sahin, deputy chairman of the opposition Democracy and Progress Party (DEVA), told AFP.

DEVA was launched last year by Ali Babacan, a former Erdogan ally who won the West’s trust as economy minister.

‘Not sincere’

Sahin dismissed Erdogan’s move as “absolutely not a sincere idea”, describing it instead as a belated response to opposition parties’ attempts to dilute the executive presidency.

He surmised that the president’s team realised that “for the first time, they weren’t setting the agenda. They lagged behind the opposition.”

Last month, Babacan and Kemal Kilicdaroglu of the main opposition CHP party agreed to work together on a “strengthened parliamentary system”.

Aware of these efforts weeks before the president took his stand, Erdogan’s coalition partner Devlet Bahceli of the ultranationalist MHP branded attempts to tinker with the executive presidency as “proof of desperation”.

Bahceli also suggested changing the law on political parties, further fuelling speculation that he wields outsized power despite being Erdogan’s junior partner, and was a major instigator behind the president’s call for a new basic law.

The MHP leader soon also backed the move.

But, like DEVA’s Sahin, a Western diplomat was sceptical that Erdogan is angling for actual changes.

“In the short term, the main objective seems to be to divide the opposition by forcing parties to take a stance on the constitutional debate which will probably be framed along the lines of ‘with or against Turkey’,” the diplomat told AFP.

‘Not serious’

Some think that if Erdogan does have anything specific in mind, it could be about scrapping an electoral rule that requires a presidential candidate to garner more than 50 percent of the vote to avoid a second round.

“At this stage, this is not a serious or a well-developed proposal,” said Galip Dalay of the Robert Bosch Academy and Chatham House.

But “if he goes for the change of constitution, his main goal would be to change the requirement of the election of the president,” Dalay said.

Aysuda Kolemen of Berlin’s Bard College agreed, projecting a scenario in which the opposition would have to rally behind a single candidate to challenge Erdogan in the next presidential vote, expected in 2023.

“If they can’t, Erdogan can win again,” Kolemen said.

But nothing is certain. Last week, the independent newspaper Cumhuriyet said the 50 percent-plus-one threshold would remain unchanged.

Tough sell

Either way, Erdogan faces an uphill struggle to get any new constitution approved.

Under Turkish law, changes require 400 lawmakers to pass without a need for a referendum. With 360 votes, a proposal can be put to the people.

Since Erdogan’s AKP party and the MHP have only 337 votes, they would need to work with at least some of the opposition to get changes through.

Another question is whether the public would support a new basic law.

“Selling a new constitution just four years after a profound overhaul is not going to be easy,” the Western diplomat said.

DEVA Party’s Sahin voiced similar thoughts.

“The changes are so new. Won’t people ask, do you want a constitution for you or for society?” Sahin asked.

“Unfortunately recent constitutional changes turned into something done for one man’s welfare and future. So it’s not possible for the public to support it.”