What is agitating the minds of many Nigerians today is the question: when will this economic travail end? When will the light appear in the tunnel? These are people once ranked as top of the ‘happiest people in the world’. But at the time, however, Fela Anikulapo-Kuti saw the classification as delusional and that rather it was a people “shuffering and Shimilng” amid lack of the basic necessities of life. Confronted with President Tinubu’s economic reform and the attendant hardship it is no longer ‘Shuffering and Shimiling’ but hungry and angry.

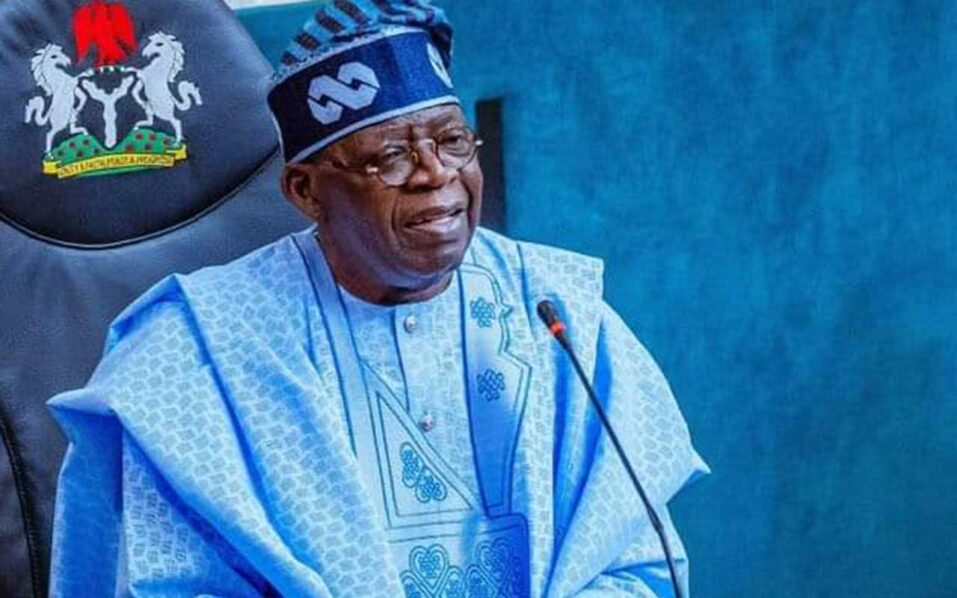

The President remains resolute on his plans, re-assuring that there is light at the end of the tunnel of economic hardship, and pleading that Nigerians tighten their belts while members of the political class, well fed, loosen theirs, a demonstrable case of monkey dey work, baboon dey chop. There have been a number of economic reforms in Nigeria but in all cases the outcome has been a déjà vu.

The Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP) of the Babangida administration, introduced in 1986 sought, amongst others: to restructure and diversify the productive base of the economy to reduce dependence on the oil sector and imports; to achieve fiscal and balance of payment viability over the medium term; to lay the basis for sustainable non-inflationary growth over the medium and long term. The policy resulted in serial devaluation of the naira. It did not achieve the economic objectives envisaged. Rather, it resulted in dislocation of the economy and pauperisation of the citizens.

The National Economic Empowerment and Development Strategy (NEEDS) was an economic reform blueprint of the Obasanjo Administration the cardinal objectives being: Reforming Nigeria’s government and institutions through fiscal reform, civil service reform and debt restructuring; Encouraging the growth of the private sector through privatisation, infrastructure investment, monetary policy stability and financial sector reform; Increasing human development through investments in areas such as education, employment and healthcare.

Modest achievements are on record which include: Banking sector reform; Telecommunication – deregulation and privatisation; Debt forgiveness ($30 billion of external debt); Stable exchange rate; Increase in external reserves i.e., from $4.9 billion in 1999 to $41 billion as at 2007 excluding $12.4 billion paid to the Paris Club of creditors. There was the monetisation policy of the administration to curtail public recurrent expenditure, institutionalise thrift and transparency. The policies of the administration, laudable as they were, have not been sustained by successive governments, and in some cases, there have been complete reversals. Clearly, sustainable development anchored on sustainable policies of governments has been elusive resulting in ad hoc system of governance at all levels. The need to address the political imperatives for sustainable incremental governance is sine qua none.

President Bola Ahmed Tinubu as governor of Lagos State had a challenging time with President Obasanjo when he created 37 Local Council Development Areas as prelude to transforming them to Local Government Areas in accordance with the processes prescribed in Section 8(3) a-d; (4-5) of the 1999 Constitution. It is instructive to note that the processes terminate in the National Assembly as required in Section 8(6) viz: ‘For the purpose of enabling the National Assembly to exercise the powers conferred upon it by subsection (5) of this section, each House of Assembly shall, after the creation of more local government areas pursuant to subsection (3) of this section, make adequate returns to each House of the National Assembly.’

Regrettably, Obasanjo’s administration failed to take advantage of the move by Lagos State to set in motion the processes for review of the number and distribution of Local Government Areas in the country for equity. For instance, juxtaposed with Kano State, (population 9.4 million, Area 20,131km2, LGAs 44), Lagos State, (population 9.1 million, Area 3,345 km2 , LGAs 20), (National Bureau of Statistics, 2006), it is evident that allocation of LGAs to States was disproportionately skewed in favour of landmass and less of population density. This is more evident for Jigawa State, a chip off Kano State, Population 4.3 million, Area 23,154 km2, LGAs 27. Thus, a posteriori, Lagos State was justified to seek to create more local government areas based on its population, particularly that LGAs count towards aggregate revenue allocation to States from the federation account.

There is the subsisting issue of the place of LGAs in a federal system. Federalism is a ‘mode of government that combines a general government (the central or federal government) with a regional government (provincial, state, cantonal, territorial or other sub-unit governments) in a single political system, dividing powers between the two’ (WIKIPEDIA).Section 2(2) of the 1999 Constitution states: ‘Nigeria shall be a Federation consisting of states and the Federal Capital Territory.’ Implicitly, LGAs, though a third tier of government, is not a federating unit and its autonomy as being canvassed must be understood in the context of a sub-unit of State with powers to run its affairs in line with the principles of subsidiarity. This underscores the provision in section 162(6), inter alia: “Each State shall maintain a special account to be called ‘State joint Local Government Account’ into which shall be paid all allocations to the Local Government Councils of the State from the Federation Account and from the government of the State.”

The current tripartite arrangement for revenue allocation, – federal, state and LGA –as though they are coordinate, is anomalous and antithetical in a truly federal system. The recent judgment of the Supreme Court for direct allocation of funds from the federation account to the LGAs overriding the provision of the Constitution on it strengthens the unitary system and is unhelpful to the advocacy for decentralisation of governance.

The advocacy for a truly federal system recognises that LGAs are a creation of State and the relationship of the latter with the central government is centrifugal by which, according to Nwabueze, ‘Each Unit including the Central authority exists as a government separately and independently from the other, operating directly on persons and property within its territorial area, with a will of its own and its own apparatus for the conduct of affairs and with an authority in some matters exclusive of all others.’

In a keynote address in 2017, President Tinubu, then as APC chieftain, advocated for true federalism and justified it on grounds that: ‘In so doing we attain the correct balance between our collective purpose on one hand and our separate grass root realities on the other.’

Now that President Tinubu is in the saddle, how soon will this be? Our collective purpose and our separate grass root realities speak of a country in dire straits confronted on all sides by debilitating socio-political, economic and security challenges. These challenges are surmountable only on the condition that the political question of our corporate existence is courageously addressed through a brand new constitutional framework and Project 2027 should not be a distraction.

Professor Ighodalo Clement Eromosele is Former Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Academic) Federal University of Agriculture, Abeokuta.