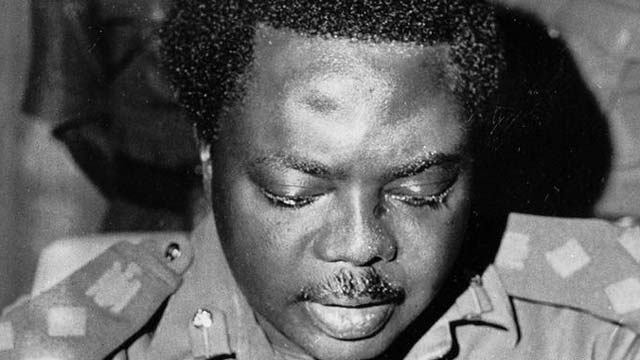

February 13, 1976, was General Murtala Ramat Muhammed’s death day. Our historical trajectory may have taken a different path had Muhammed escaped his assassins 42 years ago. But he did not and we paid and continue to pay dearly for it.

Muhammed led an extraordinary life. His death, dramatic and shocking, reverberated across the world. When he came to power on July 29, 1975, it was in a bloodless coup ending the nine-year-old regime of General Yakubu Gowon. The coup was a well-choreographed events and everything moved with military precision. Gowon was away for an Organisation of African Unity Summit. Explaining the coup during his maiden broadcast on July 29, 1975, Muhammed declared: “In the endeavor to build a strong, united and virile nation, Nigerians have shed much blood. The thought of further bloodshed, for whatever reasons must, I am sure, be revolting to our people.”

It was Muhammed who introduced the concept “with immediate effect” to our national lexicon. He announced the sacking of Gowon and all the 11 military governors and the civilian administrator of East Central State (now Imo, Anambra, Ebonyi, Enugu and Abia states) and their immediate replacements. Colonel Anthony Ochefu became the first military governor of East Central State in replacement to Dr. Ukpabi Asika. Lt. Colonel Muhammadu Buhari became the military governor of then North-Eastern State (now Borno, Yobe, Bauchi, Gombe, Adamawa and Taraba). He announced a 22-member Supreme Military Council to make laws (a function now being performed by the 469 members of the National Assembly).

“Fellow countrymen, the task ahead of us calls for sacrifice and self-discipline at all levels of our society,” he declared. “This government will not tolerate indiscipline. This government will not condone abuse of office.”

Those were the days of great excitements. Then the purges began. Those identified by the regimes to have fallen below its invisible line of discipline, productivity and loyalty, were sent out of the public service, the military, the judiciary, the academia and the diplomatic service. It was not a tidy exercise and many innocent people were cut in the net with the guilty. It shook the public service and destroyed its stability and the tradition of permanent employment.

When Muhammed was killed he was just 38. Yet he packed a lot of activities into his short eventful life. He came into prominence in July 1966 as a 28-year old major when he led the revenge coup that toppled the government of Major-General Thomas Aguiyi-Ironsi. Both Ironsi and the military governor of the West, Lt. Colonel Adekunle Fajuyi, were part of the scores of soldiers who were killed during that bloody coup. Ironsi’s Chief of Army Staff, then Lt. Colonel Yakubu Gowon, had led some soldiers from Bonny Camp on Victoria Island to the Ikeja Cantonment. There Gowon was holed up for two days and later he was made the new military Head of State. He was just 32.

Few days later Gowon pardoned Chief Obafemi Awolowo, who was the leader of Opposition during the ill-fated First Republic. Awolowo was serving a 10-year jail term in Calabar Prisons for treasonable felony. Gowon personally received Awolowo at the Ikeja Airport. Events were moving so rapidly and there was no arrangement to transport the newly freed statesman to his house. One young military officer stepped forward and offered to give Awolowo a ride. He drove Awolowo to Ikenne, in the present Ogun State.

“Young man, you will go far in life,” Awolowo predicted to the soldier. “What is your name?”

“Murtala Muhammed.”

By the time I met Muhammed’s widow in 1986, he was far gone. I had been sent by my editors in the old Newswatch to interview Mrs Ajoke Muhammed, widow of the late Head of State. She was then having a shop at the Tafawa Belewa Square. I cannot remember now whether I succeeded in getting the interview. She even then, after being a widow for 10 years, still looked young and with the sober aura of postponed happiness. Muhammed dominated his space and one could feel his presence meeting his demure widow. I spoke also with Dr Adekoyejo Majekodunmi whom Muhammed served as aide-de-camp when Majekodunmi was the Administrator of the old Western Region during the emergency rule of the First Republic. Majekodunmi had found memories of the earnest young soldier.

Muhammed was a controversial commander during the Civil War. He was regarded as a tempestuous maverick that preferred brutal frontal assaults to the methodical maneuvering that was favoured by his colleagues including the conservative Colonel Mohammed Shuwa or even the flamboyant Colonel Benjamin Adekunle. He drove the Biafran troops from the Mid-West (now Edo and Delta) and installed one of his commanders, Major Samuel Ogbemudia, as the acting governor after the military governor, Colonel David Ejoor fled in the wake of the Biafran invasion knowing too late that the military high command in Benin had been infiltrated by Biafran sympathizers. Muhammed’s attempt to cross the Niger to Onitsha from Asaba by direct attack was one of the costliest debacles of the war.

But his boys loved him. When the boys, made up mostly of war veterans; Joe Garba, Anthony Ochefu, Shehu Musa Yar’Adua, Ibrahim Taiwo, Ibrahim Babangida and others, decided to topple Gowon, they insisted that Muhammed must be the new head of state. They also insisted that two other old war time commanders, the methodical Olusegun Obasanjo and the unflappable Yakubu Danjuma, must join Muhammed to form a ruling triumvirate. Muhammed reluctantly agreed. Nigerians were to witness activism in government as never before and never since. We walked with our heads held high.

The world took notice. Muhammed installed the committee under Justice Akinola Aguda that recommended the transfer of the Federal Capital from Lagos to Abuja. He created additional seven states. He announced the establishment of six new universities. He set up the Transition Programme that cumulated in the hand over of power to elected President Shehu Shagari on October 1, 1979. His Constitution Drafting Committee under Chief Rotimi Williams gave us the presidential system of government we are still using till today. Yet he was in power for barely 201 days.

He led Africa to oppose Portugal and the apartheid regime of South Africa in the African liberation struggle of Southern Africa, especially in Angola, Zimbabwe, Mozambique and Namibia. He once contemplated annexing Equatorial Guinea when it became apparent that the neigbouring country off our coast was flirting with South Africa. He delivered the epochal speech, Africa Has Come of Age, to a roaring applause at the OAU Summit in Addis Ababa.

On the day Mohammed was killed, his car was caught in the early morning traffic of Lagos. He had dispensed with the expensive outriders, the howling convoys and the panoply of power that was the hallmark of Gowon and his governors. He was alone with his driver, his orderly and his aide-de-camp. No extra security, no back-up car. It was this simplicity that his enemies seized upon to rob humanity of Muhammed’s priceless service.

Since then, power has returned to its old ways, its odious panoply, its expensive accouterments and its sickening majesty. The cost of maintaining the men and women of power today may be why our countrymen and women are getting poorer by the day despite the increment in the national budget. We owe it a duty to the memory of Muhammed to check the cost of governance and curb the cult of the big man.

[ad unit=2]