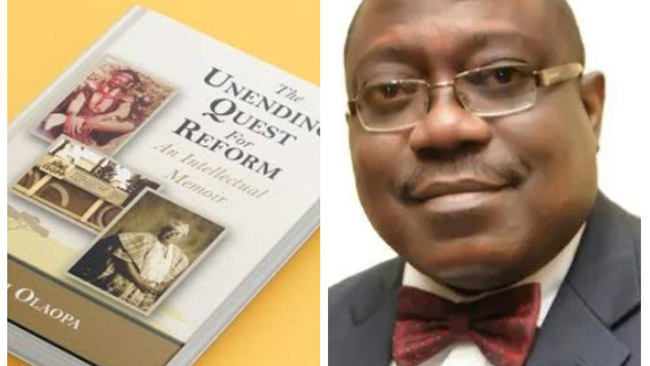

In Books and Becoming, Olaopa offers the rationale for his bookish life and the obsessive place that the search for knowledge occupies in his life. “My entire life has always been defined and shaped by books,” he declares unapologetically.

As an affirmation and testimonial to this apologia, the reader is taken through a kaleidoscope of Olaopa’s dialogical relationships with books, beginning from Daily Sketch, a newspaper which his father daily purchased and which he propitiated regularly to the god of his precocious mind.

Olaopa also holds like a totem his encounters with the genie in the genius of Prof Ojetunde Aboyade and how, in Form Three, he masticated the generally considered bony offering of Wole Soyinka’s The Man Died. Then, he began to fill his mental barn, at that precocious point in his life, with works on historical heroes like Galileo Galilee, Queen Amina of Zaria, Mansa Musa and down to Archimedes.

Among his classmates, this exemplary but unexampled relationship with books earned him the sobriquet Azikiwe, a literal reading of the “book – iwe” in a Yoruba reading of the name of Nigeria’s first president, Nnamdi Azikiwe.

Here too, the reader is led into the near marital disharmony that books were to cause in the author’s family. Finding it difficult to understand Olaopa’s incestuous consanguinity with books, the author confessed that his wife, at the teething stage of their matrimony, thought he was arrogant and perhaps, selfish.

The woman, who was later to be a convert to her hubby’s life journey of spiritual affinity with books, found it difficult to penetrate this book obsession and felt he was selfish to carve a solitary world for himself inhabited only by him and his army of book companions.

Right from here, the reader will quickly realise that reading The Unending Quest has the potential of offering imperishable quips, per page, of the book. This reviewer has his own copy of the book pockmarked with pencils underlining those rich lines and which he has hoisted to lusciously enrich his life.

One of those quips is where Olaopa sees his life journey as one constantly at the entrance of Apollo’s temple at Delphi, engaged with the graffiti, “Man, know thyself.” The second is Olaopa’s verdant discovery at the altar of Plato which taught him “the embryonic understanding of the relationship between knowledge and social construction.”

One major nuance of The Unending Quest is its simplification of staid philosophical schools and the offerings of their proponents. Chapter three of the book is one of those. The Republic of Plato is lent to explain Olaopa’s intellectual journey which he confessed wasn’t triggered from the four walls of the classroom but the existential agony he encountered when, in 1965, as a young boy, he escaped the gory bloodthirstiness of Western Region’s deadly political violence which nearly killed him.

Deploying the large expanse of intellectual frameworks he acquired from reading the works of philosophers like Plato, the philosopher whose ancient Athens and its declining democratic fortunes constituted the hub of his philosophical obligations, Olaopa’s life quest too got enveloped by the quest to provide answers to that Platonic quest, “how can we build a city on the foundation of justice?”

Apart from the tissues of precocious audacity that he acquired from youth, in The Unending Quest, Olaopa credits the University of Ibadan as where he acquired a lifelong intellectual armament, capacity for discursive engagement and boldness that have proved invaluable in his adult years.

UI, as it is fondly called, the book recalls, was where the young Tunji was given a clear vision of the world. It was the place of incubation and maturation for his idealism and which moulded the man who would later mutate into one of Nigeria’s foremost intellectual public servants. It also taught him the worth of institutional values and he imperishable values of the intercourse of ideas and ideals.

The Unending Quest is however not a book ordered in a sequential chronology. For instance, while it begins with a chapter entitled Books and becoming, it was not until page 42 that it narrated a major occurrence of the author’s life at his birth. In this chapter, with the title, In the valley and shadows of death, the author avails the reader of a major existential travail that he underwent while growing up. As is the book’s renown, this chapter begins, not without a major philosophical quip to explain the binary of boom and gloom that life is renowned with.

“From birth to death, the trajectory of life is marked by all kinds of experiences; the pleasurable and the most difficult, the sinister and the benign… the bitter and the sublime.” It was in the cusp of this that he narrates his mother’s encounter in 1960 at the annual baby show in Okeho where baby Tunji, without “a prize-winning physiognomy” caught the attention of a Reverend Sister who delivered a message to wit, no matter the challenge the author’s mother encountered grooming the child, he was never to be taken “outside the faith.”

Thus, when in early life, he encountered a head-cracking recurrent pain that defied all prognoses and even spiritual medications, Olaopa took this existential travail, which almost drove him to the point of suicide, as one of the agonizing experiences that come with the binary offering of life.

In Further philosophical reflection on my spiritual journey so far, Olaopa, deploying philosophy, agonizes about Pentecostalism leaving the most cogent route of faith and its slithering into what he termed an absolutist theology.

In virtually all other chapters of the book, the reader has availed a peep into the fecund administrative career experience of this numero uno intellectual public servant.

It is a very massive reflection and insights into, in the words of Professor Eghosa Osaghae, one of the writers of the two forewords of the book, “the nexuses among public policy, public administration, civil service and governance on one hand, and how these can be transformed along the paths of the reforms that seek to address the pathologies of bureaucracy.” This, Olaopa did in this book, with a philosophically in-depth and clinical knife that is delivered with the aid of scientific analyses.

To be continued tomorrow

Adedayo, PhD, a public affairs analyst, wrote from Lagos.