Those who know his work, will know the limitless range of backdrops against which he works. They will know how he can capture, in the midst of material lack and obvious hardship, the ineffable grace and dignity of Americans of African descent living in America and of Africans living on the African continent.

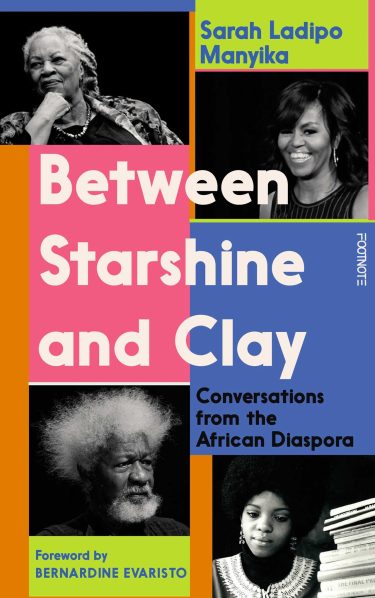

Leveraging a wide knowledge of the aesthetics of her writer’s craft, Manyika’s presentations, like Higgins’s visual masterpieces, express the spirit of the personalities they capture. But these 2 artists, the younger and the veteran, achieve an extension of their visionary gaze beyond the person, to capture also the spirit and dignity of place. Manyika’s guests are based in South Africa, United Kingdom, United States, Zimbabwe, and in Nigeria if you include her autobiographical notes which evoke and reinforce many central themes of the journeys narrated in Between Starshine and Clay.

I get to read some wonderful books. But how many of them demand I pay attention to the way the author has built them? That I focus special attention on the actual building? One can’t engage with Starshine without stopping to admire its canny architecture, achieved by an accomplished writer.

I take an aerial view of the entire text and what emerges looks like a Roman amphitheatre. Or is it a concert hall? I see an arena –it’s also an orchestral pit – with 12 huge personalities inside it. The 12 are Manyika’s orchestra of minorities. She’s in there with them as the conductor. At some distance, on an elevated floor, is what I will term the vomitorium – a passageway of rooms encircling and overlooking the arena. Above the vomitorium hangs a large, bold signpost. The text: Notes of a Native Daughter.

The rooms I see are archives holding Manyika’s colourful arrangement of Notes. Doors lead from one archive into the next. The Notes are autobiographical texts echoing the multiple concerns and themes of the music pouring out of the pit.

Inside the vomitorium, the attentive reader admires the way the notes unite in our ears with the music rising from the orchestral pit below us – the arena of titans. This is a one-of-a-kind composition: an eclectic, powerful, rich composition of themes, concerns, petitions and longings and the reader must visit each of the archives located across the length of the vomitorium to enjoy the entirety of the music.

Each archive is named. We have for example, Arab in France, Oyinbo in Nigeria, Coloured in Zimbabwe and Black in America. The last one, called, The White Continent, is a vast record of the author’s incredible exploration of the South Pole and for us the readers, it is a well-crafted exit out of the amphitheatre.

The Acknowledgements section of Starshine merits a read, opening with a brief summary of the way Manyika has conceived her book. It is no ordinary concept and as the terminus of her own journey, The White Continent represents the book’s structure at its most dynamic. And here is Manyika’s final gift – a vision that extends beyond the 12 titans to accommodate an encounter with 2 incredible, world record breaking women, neither of whom is of African descent. Preet Chandi and Hannah McKeand are respectively of Asian and European heritage. So, in addition to the shudderingly alien landscape, the blinding brightness and glacial temperatures of the South Pole, The White Continent brings to our attention, the trans-racial, trans-continental, intersectional feminism that forms a cornerstone of the author’s vocation.

The architecture of this book is so dynamic, so surprising, that I can only share Evaristo’s wonder: “Between Starshine and Clay is quite unlike anything I have ever read…”

Like a Mule Bringing Ice Cream to the Sun is Manyika’s acclaimed second book. In his review, novelist Andrew Blackman lays emphasis on a theme the author explores: it is the divergence that often exists between the way the world sees us and the way we experience ourselves.

In the autobiographical Notes Manyika brings to Starshine, her 3rd book, not only do we find her embracing the syncretism that defines her multi-cultural, multi-faith, bi-racial childhood, she demonstrates a positive acceptance of the world’s multiple takes on her light-gold complexion. She seems at peace with the world’s multiple takes on her complexion’s provenance and based on that provenance, the divergent assessments of her significance as a human being.

It seems likely that her photojournalist’s gaze was born out of this peaceful acceptance of her syncretism. Her plurality is likely the force that has refined her gaze and drawn her so powerfully to phenomena that are very specific and singular within local settings.

She speaks lovingly about her calling:

“Wondering about other people’s life stories is what I do…(I) find that my eye is constantly drawn to stories of people in Africa and its Diaspora…Take the middle-aged woman dressed in iro and buba whom I see in Berlin, sitting on a park bench with an arm around a white child. She reminds me of the woman in Njideka Akunyili Crosby’s painting, Mama, Mummy and Mamma and I wonder…what is this woman’s story?”

Her portraits of the chosen 12 are multi-media collages – richly hued stills in motion picture narratives. The guests tell their stories moving back and forth in time. Their stories are vivid: of dreams chased after; of full lives led – of purpose; of their struggles; disappointments and victories. We hear chuckles and laughter. Her guests like to pause to remember and celebrate their friends, many of whom were destiny helpers, and part of the firmament of luminaries that they share. They are all great talkers, slowing down to share wisdom, lessons learned – to provide the shade succeeding generations need so badly as we battle to slay the dragons of racism and injustice – all kinds – that we confront along on the way.

Bernardine Evaristo’s review forms the Foreword to Between Starshine and Clay. It is the first review of the book I have read and it will be hard to rival. The Booker Prize winner highlights the scope of Starshine comprehensively and yet manages not to reveal the content of the conversations which believe me, is a difficult feat. I feel that the review work for Starshine has already been done by Evaristo and that my own engagement with the book should emphasize only a few things: those aspects of Manyika’s vision that hold a deep personal resonance for me and a handful of treasures that I mined from several of the journeys. By means of this narrower focus, I seek to attract to this book the following categories of reader:

• Those whose cultural orientation is Christian – those who like me subscribe to the idea of Kingdom government but who wonder what on earth it would look like.

• True romantics the world over

• Those like me who are fascinated by metaphors, symbols, motifs and patterns from mythology, from the Bible and from other texts, sacred and secular.

I recently revisited the world visions of Manyika’s dozen. Whether secular humanists, whether professing Christians, each of them longs for a world in which the full spectrum of our rights and in particular the right to dignity of humans of all ages, gender, hues of skin everywhere, are protected. I took my time to read through the thoughts they share and I was deeply moved. Let me give you a quick introduction to 6 personalities: 3 women and 3 men – whose expositions most impacted me.

Lord Michael Hastings is Chairman of the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) and is one of the three professing Christians in the group. He is concerned about, “an increasingly entrepreneurial and diversifying world in which children at school are not being taught the skills to reach complex defined solutions for complex problems”.

He is “motivated by people who…put the energy into changing their lives… (and by people) who want to see the wider world out there give us (people of African heritage) the time and dignity to be heard”

The American poet Claudia Rankine lays emphasis on the right to vote as being at the centre of our power as citizens. In a bid to alert us to the dangers of political passivity, she quotes Aimé Césaire, a founding father of the cult of negritude:

“And most of all beware, even in thought, of assuming the sterile attitude of the spectator, for life is not a spectacle, a sea of grief, is not a proscenium, a man who wails is not a dancing bear…”

[Excerpt from Notebook of a Return to the Native Land by Aimé Césaire]

Nobel Laureate for Literature, Toni Morrison, the powerful lead chorister in the dirge of racial injustice, references The Bluest Eye – her debut book – a tragedy about a little black girl utterly destroyed by racism. I will never, ever, forget the savage ending of that book which was my first encounter with the searing Morrision. Fictional characters from her epic novels, whose names are familiar to her readers worldwide, will follow Sarah Ladipo Manyika to the White House on her first visit there to meet US First Lady, Michelle Obama. She recalls that meeting:

‘As we stood looking at her together, I found myself joined by characters … from my bookshelves back home. These included Toni Morrison’s characters… Pecola, Golden, Sethe, Beloved, Cee, Sweetness and Bride- all dotted around the room in a house once built by slaves, a house they could never have imagined being invited to as guests, let alone standing as equals with those who were white.’

Anna Deavere Smith, an American playwright with roots in Nigeria, describes herself as a “race woman… trying to uplift the race”. She and others like her are in the trenches, fighting for freedom, in daily opposition to the ferocious half of the US population who ‘don’t think of …African American artists as truly American’. The other half of America include those souls crushed by the weight and shocking injustices bred by those divisions and the brave ones trying to heal the divisions, in the case of Ms. Deavere Smith, through pioneering theatre art.

Let’s go to Zimbabwe. Produced on his mobile phone during a night of “anxiety” and “shame”, Pastor Evan Mawarire’s video #ThisFlag, was a desperate protest against the economic and political conditions of Robert Mugabe’s Zimbabwe. How could he ever have guessed its outcomes and the destiny that awaited him? #ThisFlag unleashed “(The) largest social media movement his country has ever witnessed” and transformed this Pentecostal pastor of a small church “from an unknown man into a marked man” What #ThisFlag and Mawarire’s subsequent socio-political activism have done is to take him out of obscurity and – in his impoverished, persecuted nation – dumped on him a dangerous global recognition.

We’re back in the US where Senator for New Jersey, Cory Booker, asserts that we should all possess “a great imagination”. He calls for, “artists in every profession” because the elected leaders he looks up to the most… are “masters of poetry… (They) touch something real in themselves and connect to something real in you”.

Cory Booker’s words take me back to the “large house” with which Bernardine Evaristo opens her Foreword. I am there now, paying attention to the US senator and to the other men and women Manyika has chosen to headline her celebration. 12 titans stand in the arena but in this work of exceptional political art, collectively, they embody a dizzying range of disciplines, leanings, vocations, abilities, knowledge, honours, awards, activities and can’t you hear the foment for world transformation rising from the orchestral pit?

3 professing Christians, 1 Pentecostal pastor, 1 British peer of the realm, 2 documentary film-makers, 2 theatre arts practitioners, 2 politicians, several civic leaders, a former US First Lady, a Zimbabwe Junior President, a Senator, a BAFTA winner, a Peabody and an EMMY winner, 2 or more curators, a Guggenheim, Lannan and MacArthur fellow, 3 Professors, a nurse, a lawyer, an actress, many authors including biographers and historians and those so furnished with the history of their fields, they are living historical documents. All are champions of democracy: fair, inclusive, unifying democracy. All are activists. They are human, civil, economic, political, social, environmental rights activists. Most are artists. Isn’t this house beginning to look – and importantly, beginning to sound – like the Congress, the House of Representatives, from Cory Booker’s dreams?

Can Between Starshine and Clay not be described as a site, a state in which his longing has been made real for governance by artists? Read through the profiles with which Manyika has prefaced each of the conversations and listen closely to them. Don’t the track-records of the 12 testify to the change-making impact that their influence and wisdom, their decision-making and projects, their collective spirit and compassion, have made in the communities they serve?

I haven’t spoken to the author about her choice of 12 journeys. Why that number? Why not any other? But I would be surprised if this daughter of an Anglican minister is unaware of the immense significance of the number 12 in the Bible. It is the Kingdom number of government. The “large house” Bernardine Evaristo pictures in her Foreword, the one “with 12 successful black people sitting in their own rooms inside of it” has now been replaced in my heart with a vision of 12 elders assembled at the city gates, like the elders of ancient Israel. The city at whose gates they have gathered is the world they are birthing through their works.

Everywhere in Starshine discouragement is expressed over the too many instances of gender, racial and economic injustice but we also hear Michael Hastings talk about the progress made in Great Britain in the weighty register befitting – I suppose – a member of the House of Lords. At 102 years, the athletic centenarian Mrs. Willard Harris lifts us up with a confident list of the great strides America has taken towards a more perfect union. The ‘long, probing look’ she turns to fix on Manyika reminds the author, ‘that she cannot afford to despair, especially when (she considers) what Willard and her generation endured and how hard they fought for change’.

The multiplicity of words coming from the dozen and the myriad common features of their narratives, are choral, orchestral. If Manyika’s aim is to elicit a wider call and response, then this reader is a passionate chorister. When the 12 give voice to what they hate to see in the world, I join their protest. When they give voice to what they long to see birthed in the world, signposts appear along the road to the New Jerusalem, the heavenly city which lights up the horizons of hope secreted in my heart.

Romance. The stories in Between Starshine and Clay are romances. The 12 protagonists are knights. Their romance is with the communities they serve. These include prisoners in the UK’s criminal justice system – of great concern to Michael Hastings; these include the black women authors and publishers whose rich works would have been ignored without the efforts of Margaret Busby to include them in the great canon she has built of black women’s writings. These include the women and girls whose stories form the core of the service to the world Xoliswa Sithole delivers as a documentarian of human suffering. Sithole’s films are protests, petitions, demanding the darkness in the human condition be replaced by beauty. The spirit of romance is this beauty. Romance is loving, giving, honouring, consecrated living.

If only it could shape how governments govern; how we govern ourselves; how we perceive ourselves and interact with one another; how we perceive the planet we live in and how we enter into communion with it. How we go to war and how we administer justice. If only every sphere of our fractured world were influenced by this spirit.

Back to the Foreword where Bernardine Evaristo remarks apologetically, [because the term is over-used], that the 12 are role models. Of course they are. They are standard-bearers, crusaders whose careers have exposed the lie at the heart of the intellectual prejudice that slavery and colonisation spawned.

Some years ago, in a television interview, I heard Henry Louis Gates Jr. state that in race relations, intellectual prejudice is the final barrier. Just last year, 2022, I ran into Sarah Ladipo Manyika quite providentially in Oxford Circus, London, and she repeated to me what Gates had said. But though I believe strongly that the last barrier is not an intellectual one but the biological, the physical and therefore insuperable one, I nevertheless believe just as strongly that it is vital to crusade against intellectual prejudice. We have our work cut out for us using the shining truths about us to expose the speciousness and dangerous lies at the bottom of this particular prejudice. It has for too long sabotaged the aspirations of many people of African descent living as minorities in the 4 corners of our world.

Intellectual prejudice is a major cause of the low value placed on black men and black women; on black boys and girls and to understand it is to apprehend the urgent need to rethink our relationship with our continent and with the rest of the world. Read Wole Soyinka’s Starshine conversation in which Nigeria serves as a microcosm of the African region. The Nobel Laureate is contentious here, holding that the “sense of national belonging and appropriation” is missing from our nation; the “sense of a cohesive entity to which one can dedicate not just mind, but spirit”, is missing.

He builds an impassioned case, “You can see it even in the way (other nations) sing their national anthems. Look at their faces, when they hear their national anthem played, you can see them retreat into their interior being. It’s there, you can watch it.”

The Nobel Laureate for Literature may be well-travelled, peripatetic even, but Soyinka remains the most vocal champion of returnees. Let the shining ones bring home to Africa, that sense of belonging and appropriation, that feeling of being part of a cohesive entity, let them bring home the golden fleeces of their expertise.

Because the harsh truth is this: without the achievement of parity in the arena of knowledge production on the continent, [one that will enrich the common wealth of the world] there will be, from the rest of the world, a sustained, unbroken refusal to apply the principle of reciprocity to us which the rest of the world applies to itself. We have our work cut out for us.

Toni Morrison. Claudia Rankine. Xoliswa Sithole. Wole Soyinka. Henry Louis Gates Jr. Margaret Busby. Anna Deavere Smith. Willard Harris. Michelle Obama. Michael Hastings. Evan Mawarire. Cory Booker.

The 12 whom Manyika has assembled in Between Starshine and Clay have done a great deal more than begin the painstaking task of exposing and dismantling lies that endanger. In their own distinctive ways, each of them is leaving the world a far more hopeful place, a world whose riches are far more accessible to us than they would have been had these men and women not lived and worked in it, striving to plant bountiful trees in whose shade succeeding generations of humans will sit.