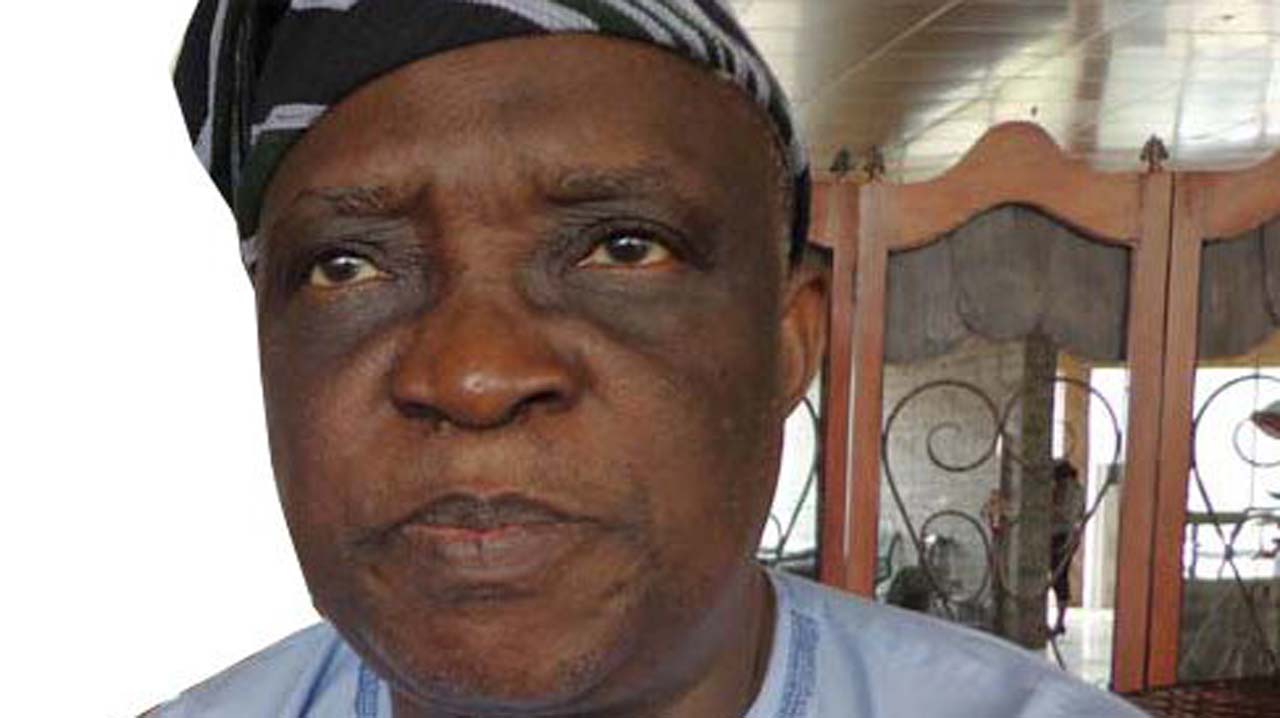

Professor Olu Obafemi, is one of our country’s pivotal scholars and writers of very deep thoughts and value. He is without question one of our foremost senior professors of theoretical and practical aesthetics who has dwelt and written on almost every subject, but his central subject is humanity.

He is a humanist par excellence. He does not joke with this column as one of its distinguished contributors and consistent readers. Not long ago, precisely on March 22, 2024, he delivered a lecture on a subject very dear to my heart and to the hearts of all patriots to the Academic Staff Union of Universities, University of Jos Chapter.

The full title of the lecture was “Government’s Commitment to Funding Public Universities in Nigeria: The past, the present and the future.” I was about to write about our new central government’s thought on the funding of tertiary education since the new government announced its plan and guidelines for loans to be granted to students of our universities.

I was going to do so here from the perspective of humanity of loans for universities’ students when I encountered Professor Olu Obafemi’s lecture aforesaid, which I consider, rightly or wrongly, a milestone in Obafemi’s canon. Every reader of this column (and every Nigerian) deserves to be provided this potent, brilliant lecture – which I hereby provide. Until it ends, as you read it, starting from today, it is my wish that the excerpts I bring you numberless hours of patriotic pleasure and heavenly happiness in these unhappy times – as you know now what you didn’t know.

Here we go.

“Education is the powerful weapon which you can use to change the world. There is no doubt about it. Education is a powerful tool for change.” (Nelson Mandela)

State funding was a guarantor of fairness. But markets in education, left to themselves, would reproduce inequalities of wealth and social capital…

Modern states elsewhere support universities because their benefits are social as well as individual, and they have been the creators of individual opportunity, social solidarity and national identity (Robert Anderson, British Universities Past and Present: Humbledon Continuum. 2006)

Preamble

It is a matter of great honour and delight to be asked to give this Lecture to our great Union at this historical trajectory of our unions and universities’ life. For someone like myself, vibrantly nurtured and nursed by the life and struggle of ASUU since 1982, when I became Secretary of the University of Ilorin Chapter and 1983 when I was elected Chairman of the same Chapter and therefore a member of the National Executive Council (NEC), my life and growth have been inextricably linked with the life, travails, struggle, and growth of the Union at all levels.

On the level of struggle, my engagement dated back to the unions first main negotiations with government in 1982. I was a mere foot-soldier in the process and the definitive outcome of that struggle is foundational to all the union’s struggle. You can just simply assume, and correctly too, that I am an active/almost a serving veteran in the life engagement of the Union, including being an official part of the government team, of the most recent renegotiation between Federal Government and University-based unions—the result of which has never seen the light of day, no thanks to Government. In recent history, ASUU Unijos has been a domain of experience and involvement for me and I am thus an unofficial, ‘member’ of the UNIJOS Chapter.

This is, therefore, indeed homecoming in many particular respects. But I have also served government, a few times, in non-Executive positions, given me ample insight to the workings of both sides.

Of Heroes…

I must mention, as this talk is on the Union’s Heroes’ Day, that it is germane to briefly reflect on the guiding philosophy of Heroism. As a student of Literature, I frequently confront the concept of heroism as a tool of analysing society and the human experience. Ideally, Heroism is predicated on people and citizens’ ideals for transforming’ civic ideals into action through courage, immense sacrifice, selflessness to achieve the highest possibilities for communities, societies, and nations.

Some pay the supreme sacrifice for these ideals to be achieved, and for which society immortalises them, if those societies have a heroic culture, that is societies where most people fight for human ideals. Some heroes succeed and live on, and thus become venerated and revered. They then serve on as lifetime inspiration as their societies grow. ‘The German Marxian playwright, Bertolt Brecht, dwelt on the question of Heroism in his play, “The Life of Galileo”. Many of us may be familiar with the story of the real Galileo Galilei, the physicist/astronomer/ mathematician who transformed, in fact revolutionised, the world’s perception of the natural; that the earth and other planets revolve around the sun, and paid the supreme sacrifice for such a rebellious truth.

In the dramatic fiction of Brecht, Galileo’s student Andrea says: “Unhappy is the land that has no heroes” to which his master replies: “No. Unhappy is the land that needs heroes”. Both perspectives are tenable. Galileo did not consummate his knowledge, was taken as lacking courage, a coward and thus a non-hero; an anti-hero. In idle societies of uncritical hero worshipping, heroes are left alone to carry society’s burden. Invariably, the heroes crumble under the weight. These are called tragic heroes. This is the kind of society where there is conformism, escape, where man’s fate is left in the hands of individual saviours.

In ASUU, where most of its members are committed to the collective struggle of renewal of their own lives and society, heroes have been here: some have left us, leaving behind their mammoth, extraordinary and uncommon exploits, which keep us and society going—The Mahmud Tukurs, Esko Toyos, Festus Iyayis, the Alao Aka Bashoruns, Tunde Oduleyes, David Jangkams, Tunde Fatundes, Aaron Gana and many others, have left us. Others are still here with us, in the trenches, leading the revolutionary struggle—where you find our leaders in the eighties and late seventies or a little less plying the road for the ideals of national redemption—Jeyifo, Olorode, Osoba, Asobie, Fashina, Awopetu, Sunmonu, Jega, Mangvwat, the Falanas, and so on, a day of heroic symbolism is in order.

Here in Jos, the symbolism is well perceived and erected. The true heroes are etched on the Wall of Fame and those who carry on with unedifying mannerism are glued to the Hall of Shame.

The Body

In all these years of the life of the Nigerian academia, and its travails, its struggle, to improve the lot of university education and the state of our nation, Funding, the provision and availability of resources to build and develop university education in the public sector, has been the recurrent, perennial and unresolved challenge and thorn in the education stakeholders’ flesh. It has been adduced by educationists that over 70 per cent of the crisis bedeviling university education has been directly attributable to funding.

Issues of inadequate welfare catering for staff and students, resource input, infrastructure, research, are all products of poor funding by the Federal government. And the struggle to make government right these wrongs has been the cause of incessant strikes by staff, especially ASUU and, to some extent, the other university-based unions. I must state here, for the avoidance of doubt, that government’s insensitivity and half-hearted responses to all these demands; also, the fact that as the ever-increasing demands of university space in the face of diminishing and slimmer resources in the nation, funding the universities continue to deteriorate, abysmally, perennially; all these led to the incessant closure of the universities and the galloping decline in the standard and quality of Nigeria’s university education.

This is why this topic to examine the nature of government’s commitment to funding university education in the public sector is not only rife, timely, germane but apt as a subject of open discourse and I thank this Chapter of our union for opening it up for further examination in order to find a solution to it in the interest of knowledge production, knowledge delivery and reception upon which our nation’s civilisation and development recline. As Professor Ojetunji Aboyade (1982), whose Lecture I have been unable to keep out of my memory ever since he delivered it at Unilorin, and I will refer to copiously here, had asserted, quite graphically,

even for its own self-preservation,’ and progress, ‘Any modern society needs some kind of university institutions where education at its highest level can be provided and knowledge can be advanced in an atmosphere of scholastic freedom, peace and comfort. The growth of nations and the wisdom of peoples are therefore intimately bound up with the flourishing of their universities.’

To be continued.

Afejuku can be reached via 08055213059.