There is an oft-repeated but seldom scrutinised assertion that the study of history as a subject was removed from the curriculum in Nigeria. It is said that the teaching of history was eradicated from the curriculum, and that is why Nigerians do not study history. But I beg to disagree.

Contrary to what many believe, teaching of history was not stopped. No policy, no legislation has ever prohibited the study of history in our schools nor prohibits the Nigerian from reading. Hence, untrue is the assertion that teaching of history in Nigerian schools has been eradicated. It is important to make this point so as to challenge and correct a narrative driven by an assertion which, in some persons, border on intellectual laziness.

Nonetheless, we must inquire: what really happened to the study of history in Nigerian schools, and what can we do about it? It takes knowledge of history to know what happened to history in our schools.

At a point in Nigeria, art subjects in general began to be marginalised and deemphasised supposedly in order to promote science and technology. Nigeria, policy makers opined, needed to catch up with the “industrial world”.

If I may be permitted to make an autobiographical note. As at the time I was in secondary school from 1974-79, we were made to believe that weak students studied art subjects, while strong and brainy ones studied science subjects. It was a thing of pride for a student to be described as a “Phy-Chem-Bi” student, that is, a student of Physics, Chemistry and Biology.

Some parents discouraged their children from studying art subjects because they wanted their children to become physicians or engineers. They preferred that their children study science subjects.

It was an era in which the sing-song was: “transfer of technology”, an epoch in which science was emphasised to the point of deemphasising arts. The intention was not to eradicate history but to advance science and technology. That logic would seem to have influenced President Shehu Shagari, in his televised address to the nation on the evening of October 1, 1979, to announce his intention to establish universities of technology in Akure, Owerri, Minna and Yola.

A university, by vocation, is a universe of knowledge from which no province of knowledge is to be excluded. But Nigeria began to establish universities in which science and technology were granted near exclusive epistemic privilege while studies in humanities were marginalised.

Given this pro-science policy, not only study of history, but also study of languages, literature, religion and philosophy became casualties. The consequences are now before us: the average Nigerian graduate of tertiary education is afflicted with memory loss, notoriously poor in written and verbal use of English and Nigerian languages, commits simple faults of logic in discussions, and is unethical in sundry ways. Be it kept in mind that ethics is not taught in the faculty of science. It is taught in the department of philosophy which is domiciled in the faculty of arts.

Now, where you have a human being afflicted with memory loss because he has not read history, incapable of communicating because he has not studied the use of language, and incapable of being logical in his thinking because he has not studied philosophy, there you have formed someone close to a monster. Little wonder our common life is characterised by interminable and seemingly insoluble disputes, debates riddled with fallacies that often end in violence. But the problem is not peculiar to Nigeria.

In 1994, the day after President Richard Nixon’s funeral, I had asked the young American university students I was teaching at Boston College if they knew why President Nixon was impeached. No one in the class knew. I thought I could help by offering a clue. So, I asked if anyone knew about Watergate scandal. Only one student knew Watergate to be a building in Washington, DC.

He neither knew what purpose the building served, nor what the scandal was. If, as at 1994, the young American students I was teaching knew nothing about the Watergate scandal that led to Nixon’s impeachment and resignation from office of President of the United States, then lack of interest in the study of history is not peculiar to Nigeria. It is a fall out of a prevailing technocratic mindset that has supplanted the sapiential mindset. There is greater interest, not in facts but in figures and gadgets, than in wisdom. Today, that interest has become even sharpened by interest in the STEM courses.

It is extremely difficult to sustain a democratic culture without studying history. Here in Nigeria, the largest voting bloc is made of young Nigerians who know very little about history of Nigeria, or have been presented with ethnocentrically slanted versions of Nigerian history, and who know little or nothing about antecedents of candidates campaigning for public office. Surely, the only beneficiaries of this loss of history are members of the political class in this country. They are able to assume public office, not just because they mightily succeed in compromising the electoral process through vote buying, snatching of ballot boxes and falsification of results, but also because their antecedents are largely unknown to the largest voting segment.

Loss of history institutionalises and perpetuates tyranny. A tyrant gets into office because voters are ignorant of his history. Assuming office, he suffers from memory loss induced by loss of history. For if he knew history, he would have known that tyrants never end well in history. Whoever does not wish to be a tyrant must study history. Then he would learn that tyrants end up in the trash can of history.

But a caveat is in order. As desirable as the study of history is, whoever wishes to study history must beware of revisionist history, that is, blatant or subtle distortion of facts, of narratives told not at the service of truth, but at the service of ideology and propaganda.

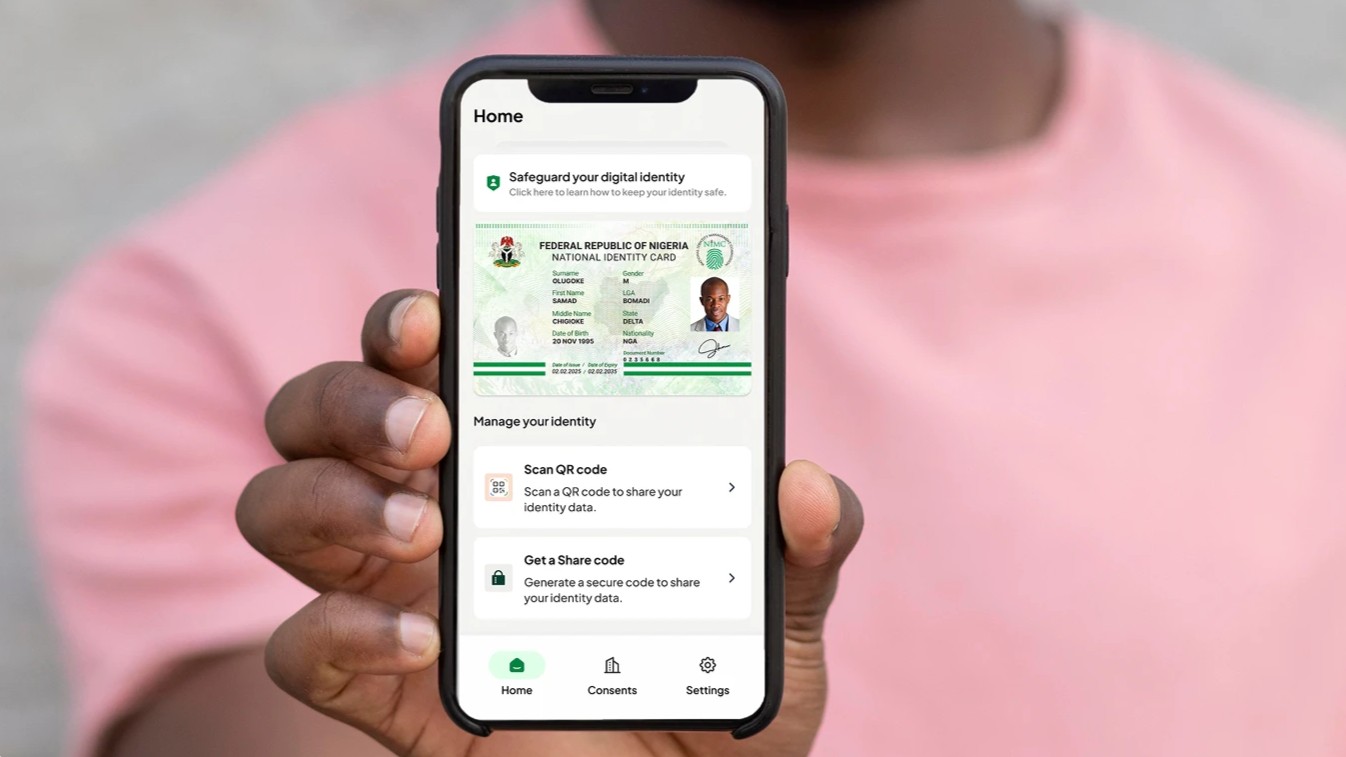

Many Nigerians, young and old, have not learnt from our past mistakes because we do not study history. However, Nigerians ought not to blame government for not knowing their history. No one stops anyone from buying and reading history books. In fact, the cell phone, when connected to the web, is the largest library in the world. We need to spend more time reading history from that library than we spend watching movies on the cell phone.

Whoever wishes to learn history is not deprived of documents. In a country where people tend to believe whatever pastors and politicians say, whoever does not wish to be deceived must read. But, as we all know, if you want to keep a secret from Nigerians, put it in writing.

Father Akinwale is Professor, Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies, Augustine University, Ilara-Epe, Lagos State.