Good morning, Mr President. I focus on the renewed debate about state creation. In the conceptual domain, there are many concepts of state. I will restrict myself to the less problematic Weberian definition that we employ to introduce students to the concept of the state. A state is an entity that is endowed with a population, territory, government, sovereignty, and has a monopoly over the means of coercion. Besides, the state is an objectified product of the social contract.

Governments within states are meant to cater to the needs of the people, and administrative units are also geared towards that purpose. To be sure, the state creation exercise accords autonomy to peoples within a multinational state. Unitary states can carve out administrative units that are co-extensive with the identity of their people.

The Nigerian state was conceived as a federation of the nationalities that make up the country. It evolved from the colonial administrative measures to the Lancaster House dialogue of the 1950s. The struggle for hegemony among the dominant ethnic groups, which I have regarded as the dominant contradiction of the Nigerian state, was and has been the bane of a functional federation. The lopsidedness of the original three regions led to the agitation for the creation of more regions. Each regional premier was involved in turf control.

Even the rulers of Western Nigeria wanted the creation of a Middle Belt State and another in the east for the eastern minorities, notwithstanding the caveat of the Willinck Commission. Forces are the centre contrived to create the Midwest region (though the peoples of the region desired it) to spite the Action Group, which desired a country-wide and attenuate its sphere of influence.

The hegemonic struggles of the social forces at the centre to have centralised control over the rest of the regions, especially Western Nigeria, spiralled into a civil war. The war was a major milestone in the attenuation of the federal essence of Nigeria by the victors of the civil war, notwithstanding the hypocritical slogan of “no victor, no vanquished.” The creation of additional states to number 12 was a tactical move by the unitary elements who controlled the central government to break the Biafran solidarity.

In Professor Isawa Elaigwu’s biography of General Gowon, Gowon argued that: “the main obstacle to the future stability in this country is the structural imbalance in the Nigerian federation. Even decree No. 8 or Confederation or loose Federation will never survive if any section of the country is in a position to hold others to ransom.” Gowon offered yet a further justification for state creation.

As he puts it, “I am satisfied that the creation of new states is the only possible basis for stability and equality as the overwhelming desire of the vast majority of Nigerians. To ensure justice, these states are being created.”

That may have been the manifest function. The fact that the creation of the states occurred three days before the declaration of separation from Nigeria by the Eastern Region, affirmed the point that it was designed to break the solidarity of eastern minorities with Biafra. Since the promulgation of Decree No. 13 of 1967, which broke the country into twelve states, subsequent state creation exercises have undermined the federal essence of the Nigerian federation.

It is important to note that statecraft demands uniting a people through the creation of what Odia Ofeimun has called “a common code of morality”. The old Bendel State exemplified that. General Babangida broke it into two to serve the purpose of his failed self-transformation project and increased the over-bureaucratisation of the state.

General Abacha, who a Spanish newspaper, El Mundo, once described as a nasty piece of work, would further augment the states to thirty-six states. It would be recalled that when the country was governed based on four regions, it made progress. As it was increased to thirty-six states, it created quasi-emperors, increased the cost of governance, while simultaneously democratising corruption and reifying impunity of state actors.

Even the recent autonomisation of the 774 local governments by a Supreme Court ruling, celebrated as case law, was itself a violation of the 1999 Constitution as amended and a mortal blow to the nature of the Nigerian federation. The supreme legislative power resides within the units of a federation as a coordinate of the centre.

Mr President, I wish to supply an important caveat here, put differently, advocate for an exceptional case. There are situations where the oppression of minorities has become so intense that autotomising them by state creation maybe germane.

For example, the people of Southern Kaduna, who have been the subject of Fulani-led genocide, deserve a state. It might be useful to envision a big picture, that is, to create a state for the Gwari people of the Middle Belt and the Southern Kaduna people. It is by no means an affirmation of the proliferation of states and the attendant proliferation of perverted elite and the cost of governance.

The above logic was what partly informed the recommendation of fifty-four states by the 2014 National Conference empanelled by President Goodluck Jonathan.

There is a refutation of the intention to create more states from the National Assembly. It has yet to deliberate on issues of state creation; however, it has admitted that the Constitution Review Committee has received over forty-two proposals for state creation. Mr President, it is more economical to collapse existing states into autonomous provinces within regions than to create more states.

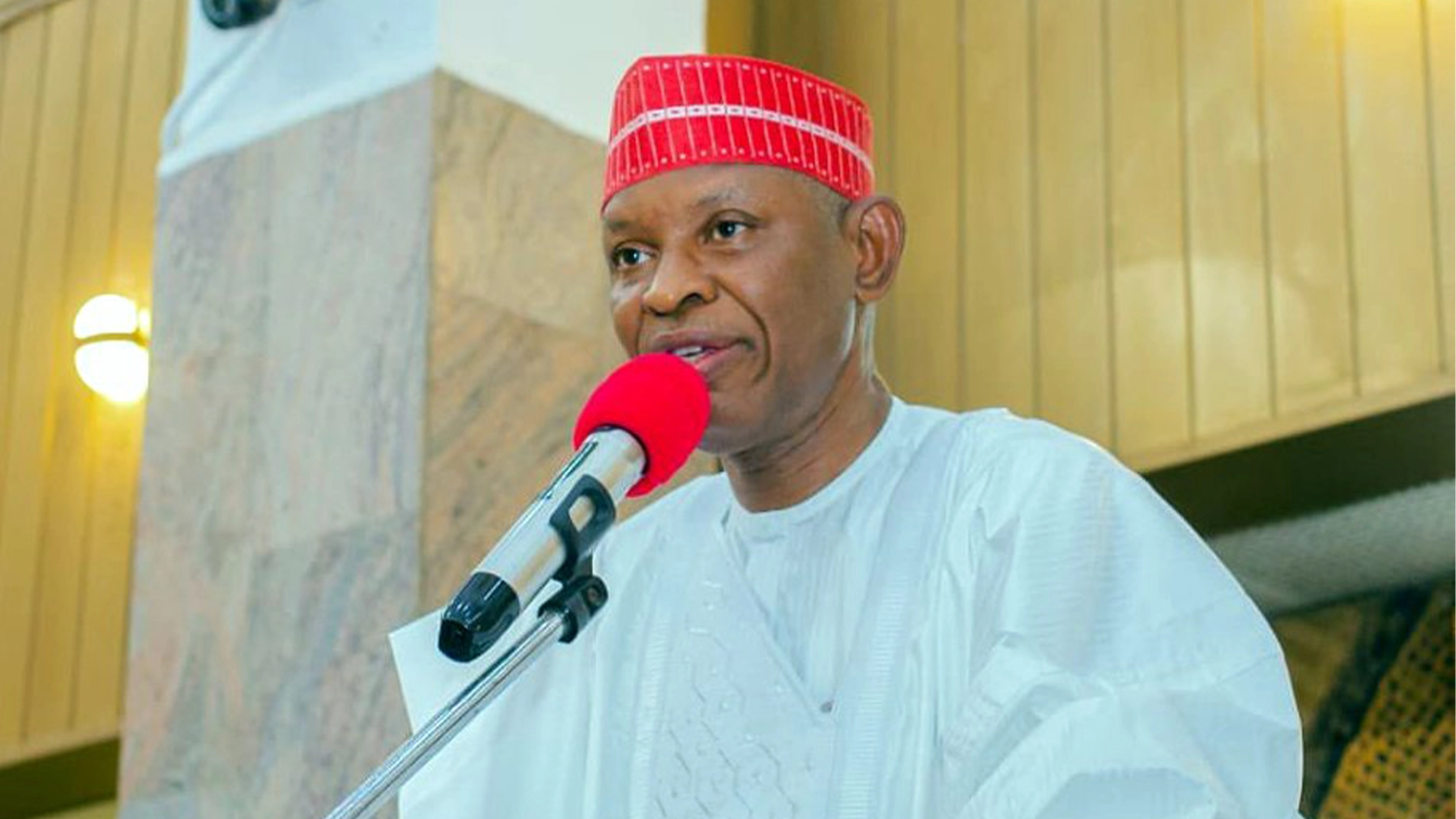

Prof. Akhaine lectures at the Lagos State University.