Fifty-three years after the countrys Civil War, more and more people are coming out with boldness to narrate their experiences during that ugly period of Nigerias history.

Examining key issues and giving accounts of the civil war, these memoirs, novels, short story collections have made post-Civil War Literature one of the most thriving genres in academic discourse.

The Nigeria-Biafra War actually lasted less than three years, between July 6, 1967 and January 15, 1970, during which time the post-colonial Nigerian State fought to bring the Southeastern region, which had seceded as Republic of Biafra, back into the newly independent, but ideologically divided the country. The then seven-year-old Nigeria went to war against its eastern region (with a population mostly dominated by Igbo, but also had Ijaw, Efik, Ibibio and other ethnic nationalities).

The 30-month conflict, which left up to two million civilians dead in the region, is the darkest moment in Nigerias history, and it continues to haunt the country. Fifty-three years after, the factors that contributed to the war, including fears of ethnic domination and political marginalisation, are still present, but not being addressed by political gladiators.

Some of the high-profile war accounts include, Cyprian Ekwensis fictionalisation of crime and disorder in post-war Biafra in Survive the Peace (1976), Chinua Achebes first-hand account as an administrator and writer in There Was a Country (2012), Chimamanda Ngozi Adichies portrayal of middle-class lives in Half of a Yellow Sun (2006) and Chinelo Okparantas centring of lesbian women in Under the Udala Trees (2015).

In Never Again (1975), Flora Nwapa, Nigerias first female novelist, shines light on the lives of ordinary Biafrans during the war. She tells the story of the war from her hometown, Oguta, relying on the day-to-day conversations of the characters to provide the reader with a sense of the climate.

Also, in Sunset at Dawn (1976), Chukwuemeka Ike approaches the War in a manner that is usually overlooked: the fate of inter-tribal marriages at its onset. Infusing humour in an otherwise tragic story, Ike lays out the charming love story of Dr. Amilo Kanu, an Igbo, and Fatima, a Hausa, and how their love and lives are tested. Ike’s account best capture

Elechi Amadis Sunset in Biafra (1973) portrays the Igbo majority as an ambitious and overbearing group going to war against Nigeria and ultimately dragging an unwilling Eastern minority into it.

In The Biafra Story: The Making of an African Legend (1969), the English author and journalist, Frederick Forsyth, details the brutalities suffered by Biafra and the survival tactics it adopted. It has since come to be regarded as a modern classic of war reporting.

The book voices outrage not only at the extremes of human violence, but also at the duplicity and self-interest of the Western governments most notably, the British, who tacitly accepted or, actively aided that violence.

In Prince Chudy Otigba’s account, the reader is taken on a route that is almost coloured by the suffering endured during the period, which many Biafran biographers have said are ‘scarcely and sensibly broached in mainstream discourse’.

An impressive trope, the book is a tale of alienation, displacement, persecution set against a wider Nigerian nation that was lost in Achebe’s There was A Country.

Titled, I Remember: The Nigerian-Biafran War, Graphic Recollections Of A Child, the book goes chronologically from conception to death, with the author given freedom to wander at will like a midfielder in a football match.

The book gives a detailed account of a growing up Nigerian child caught in the middle of the war. It graphically illustrates what life was in the Biafran enclave and how every family contributes souls as trophies of this war. I Remember weaves personal narratives of the war to good effect.

The author uses the flashback technique to interrogate the loss of innocence, a theme, whose effective use is also captured in Sometime in April, a film on the genocide in Rwanda, which vanquished over 800,000 people of both Hutu and Tutsi ethnic nationalities in 1994.

In her foreword, the writer’s daughter, Princess Emmanuella Otigba, says, “I Remember, a story about the war that broke my country, as experienced by a child and told as an adult, gave me some perspectives. It made me realise that I know these things because Ive been on a learning journey, which describes the theme of this book.”

She continues, “reading the synopsis of the writers experience put my life into perception and I believe it might do the same for a lot of people that will read this book. It takes you through the journey of what an average Easterner has experienced and the basis of what makes them who they are today.”

She sums up her foreword with the following words: In fact, as people embrace this book, let it be known that its singular theme can be summed up in a brief sentence: Ozoemena (Never Again).”

As the title suggests, this book comprises graphic recollections of a child victim of the excesses of adults whose deeds led to wanton destruction of lives and property.

The writer is the eye of the camera through which the reader sees the book. He is God’s eye and he captures the event succinctly. Intensely personal, the opening chapter graphically takes you into the book. It is not just informative; it provides a wide ride into the uncharted part of the war discourse.

Titled, Nigerian Soldiers Invade Asaba, 1967, the first chapter lucidly captures the panic, anxiety, chaos and anarchy associated with the pogrom of 1966 and 1967, which led to the war.

His imagery is concrete.

The author says, “my Mama came running, crying, searching for me and my elder sister, her first child, who was two years older than I. Mama was crying and saying in the Igbo language that Ndi Awusa abatago Asaba (Nigerian (Hausa) soldiers have entered Asaba); that Onitsha Bridge, the only access route across River Niger by land between Asaba and Onitsha, had been blown up by the Biafran soldiers to forestall the invading Nigerian soldiers from crossing into Onitsha from Asaba. There were rumours of massacres by Nigerian soldiers, going on in Asaba.”

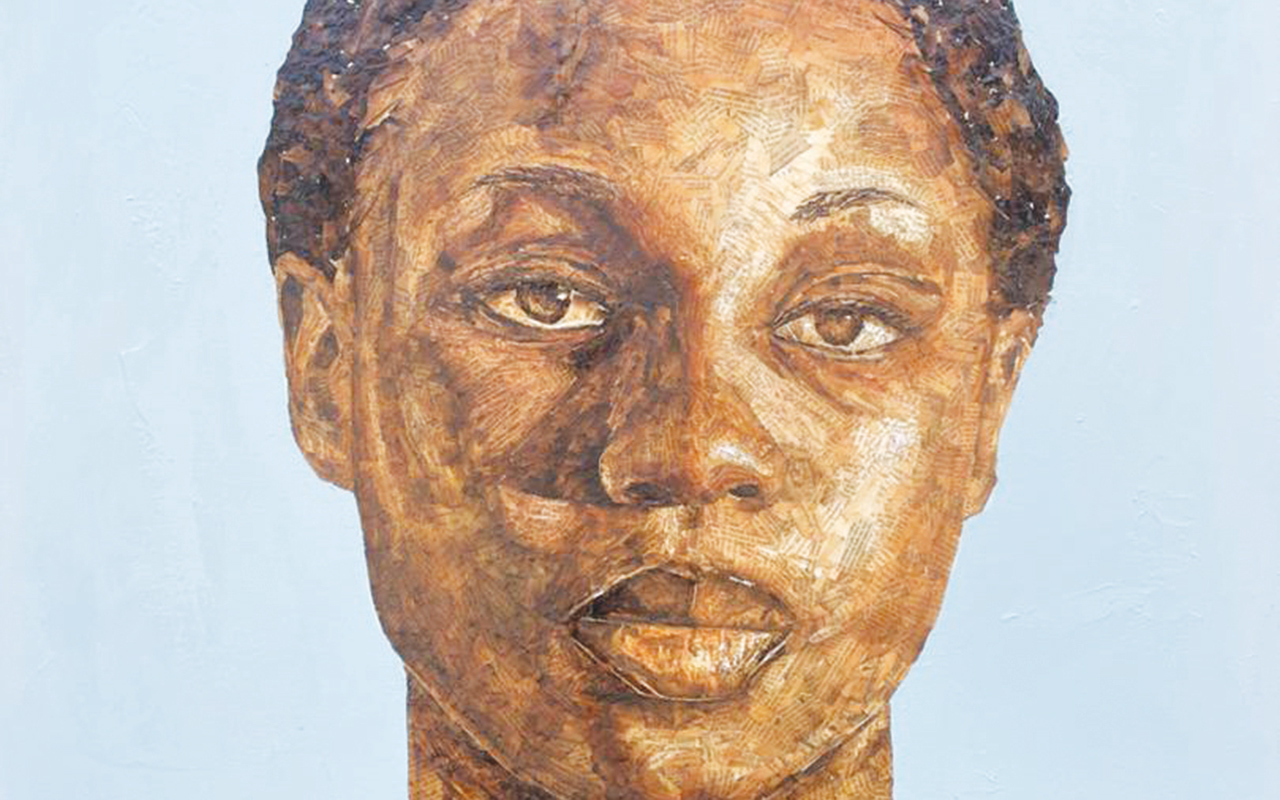

With this opening you could glean into the character of his mother: “Mama, as I remembered her then, was a very beautiful, tall black, and strong lady in her early 20s. She was nicknamed Akwete Nwanyi or Nwanyi Ghana because of her beautiful, flawless, smooth, unblemished skin and unique blackness, a resemblance to Ghanaians. She was indeed a very beautiful young lady with a gap tooth, always happy, smiling, and joyful; a pleasant personality to be with, amiable, religious, and a lover of God.”

The author, who was a child when war broke out, nevertheless, witnessed the suffering and pain, and has tried to capture its effects, especially on children and women. This makes the book a must-read for every lover of peace, not only in Nigeria but also globally. This is because war brings nothing but agony and pain and must be avoided at all costs.