It feels a bit surreal to be writing about the death of Prince Rogers Nelson just days after an even bigger curtain has fallen. On the night when I went to sleep with the news that Muhammad Ali was in a critical condition in hospital at the age of 74 and after three decades of debilitating Parkinson’s disease, I knew he would be gone by the time I awoke, unbearable though that eventuality seemed to me. Prince’s death, however, was totally unexpected, a jolt out of the blue.

I was at a culture festival when a cursory scroll through twitter brought up the ‘RIP Prince’ tweets that caused my breath to quicken. I knew only one person in my immediate vicinity, someone I had only just met for the first time an hour or so before. I went up to him and said urgently, amidst all the noise, “Prince is dead!” As my listener’s expression changed to register understanding, I knew the moment was both resonant and pointless, for what could anybody do about it? I went back to my seat, ever so lonely in the crowd. Prince’s death, as with the decades when I had lived vicariously through his music, was personal.

Only three weeks or so before, I had been one of thousands that marveled at the sheer fabulousness of his passport photograph when it hit the internet. With a glorious Afro and silken skin, he looked serenely into the camera with his famous doe eyes, complete with the ubiquitous eyeliner. He was “almost unnecessarily handsome at 57,” to quote the UK Guardian’s Alexis Petridis. Prince looked supremely yoda-like, and death seemed far off.

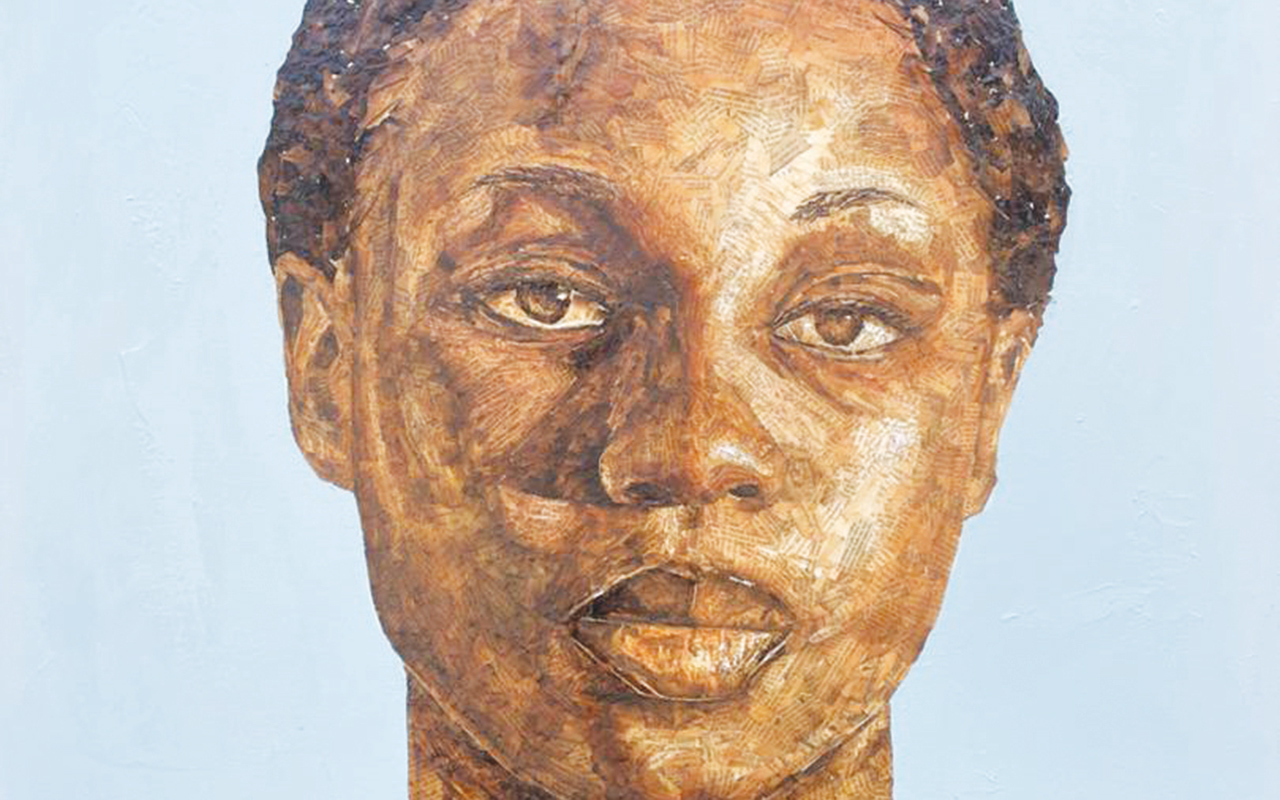

He was one of a select band of legends concerning whom I harboured a fear of bad news. Now, watching performances from his ‘I Wanna Be Your Lover’ period circa 1980, clad in the revealing costumes he favoured then, one notices he had an appreciable muscular build. Some of the muscle had been shed by the time of ‘Purple Rain’ (1984); he was svelte and chiseled as a sculpture by the time of ‘Kiss’ (1986). He grew more willowy in the later years, his sleeves almost billowing. Seen on rare occasions on TV, standing on a stage at some award ceremony or other, he had a luminescence. A hush would fall on the star-studded audience in the presence of true music royalty. He had become a precious thing.

I never got over the shock of hearing his deep speaking voice, miraculously emitting from the same vocal chords that sang funky falsetto on many hits. He was an enigmatic combination of fragility and resilience. As the years rolled on after the demise of his great musical rival, Michael Jackson, I would look at Prince on the TV screen, thinking: Look at you, you survived!

Prince appeared to weather the decades relatively unscathed, seeming to keep the ravages of fame at bay. As Jackson frayed at the edges under the public gaze, transmogrifying into the so-called ‘Phantom of the Popera’, Prince’s own eccentricity never threatened to consume him. The one tragic detail in his story – the death of his only child a week after birth – only inspired the empathy of fans.

Known for a time as ‘The Artist Formerly Known As Prince’, he was a true artist. He was our Mozart, channeling all his talent and energies into the creative endeavour. Music, he insisted, was not a thing of pride at all but a gift to be shared with the world. “There isn’t anything non-music. I am music,” he had said, when asked about his non-musical pursuits. If he had a fitness regime, we never knew the details. He didn’t indulge in activities that served to demystify some superstars. He came to London regularly enough in the 80s and 90s but was never photographed running through Hyde Park with a fitness trainer and a bodyguard in tow in the style of Madonna. When he did the seemingly mundane – as with newspaper reports that he had joined the queue for a burger at a fast food restaurant somewhere on the British Isles, wearing his signature heels, and to the amazement of regular clients who fell off the line – it was hyperreal, portraying him as an invincible, otherworldly persona, further cementing his allure and mystique. British tabloids liked to describe him as “pint-sized” back in the day, but he only loomed larger in the imagination.

We’ll never know if the burger queue incident actually happened; no images surfaced. We now know he was a familiar figure cycling in and around his Paisley Park estate in Minnesota, U.S. But we didn’t see the photos either, not until after his death. He was in total control of his own image and career. None of the usual baggage of stardom for him, it seemed. He was reported to be a stickler for clean living. There were no known arrests, no previous history of drug abuse, no bust ups in clubs; he teased music fans with his sexuality but there were no sex scandals. All of which made his sudden demise, mired as it was in an opioid overdose, all the more bewildering.

“I am transformed,” he had tweeted, only days before. When his plane made an emergency landing a week before his death, I stopped for a second on seeing the news, then I shrugged it off. He would be all right, I thought. “Wait a few days before you waste any prayers,” he told fans at his last public appearance. And then he was truly transformed.

It’s not every day you hear an inconsolable Naomi Campbell weeping down a phone line to CNN, or see political commentator Van Jones fighting back tears on live TV, or Motown legend Stevie Wonder crying for his lost brother in music. The CNN studios went purple to commemorate the passing, as did great landmarks around the globe. Not even the cover of The New Yorker was exempt.

As Ebony Magazine put it, “When the news broke about Prince’s death, it took our collective breath and seemed that almost instantly, the whole world turned a shade of purple.” As for me, I had the gardener plant a small field of purple, as my tribute to His Royal Purpleness.