Nestled in the serene Elsie Femi Pearse Street, Victoria Island, Lagos, Tiwani Contemporary is what the journalist Yinka Olatunbosun has described as a ‘spreadsheet-baring’ statement pieces.

Nestled in the serene Elsie Femi Pearse Street, Victoria Island, Lagos, Tiwani Contemporary is what the journalist Yinka Olatunbosun has described as a ‘spreadsheet-baring’ statement pieces.

The residential building with which the gallery shares a sizeable compound stands out in its environment on account of its fresh white paint, elegant palm trees and sleek glass windows.

The gallery is a dream come true for the Greek gallerist, Maria Varnava, who lived in Nigeria as a child but now resides in England, where she founded Tiwani Gallery in 2012.

Since Tiwani Contemporary arrived in Nigeria in February 2022, the 2,000 square ft. purpose-built gallery has become a ‘diasporic consult’. And as a home to diasporan arts, the work in its sleuth has gravitated to the best of contemporary Africa.

The gallery’s outdooring was with the British-Nigerian painter, Joy Labinjo, whose show, Full Ground, which was curated by Nigerian-American artist and curator, Temitayo Ogunbiyi, who coincidentally, is exhibiting in the second show of the gallery, attracted rave reviews and critical interrogation for its perceived, ‘Nudist’ content

The title of the second show is from Mary McCarthy’s debut novel, The Company She Keeps, a series of six cleverly interlinked New York short stories, which made nearly as much of a splash when it was published in 1942.

Curated by Adelaide Bannerman, the exhibition, which runs from May 28 to August 13, 2022, arrives carrying on its shoulder, a wonderfully compendious confirmation of the intellectual woman.

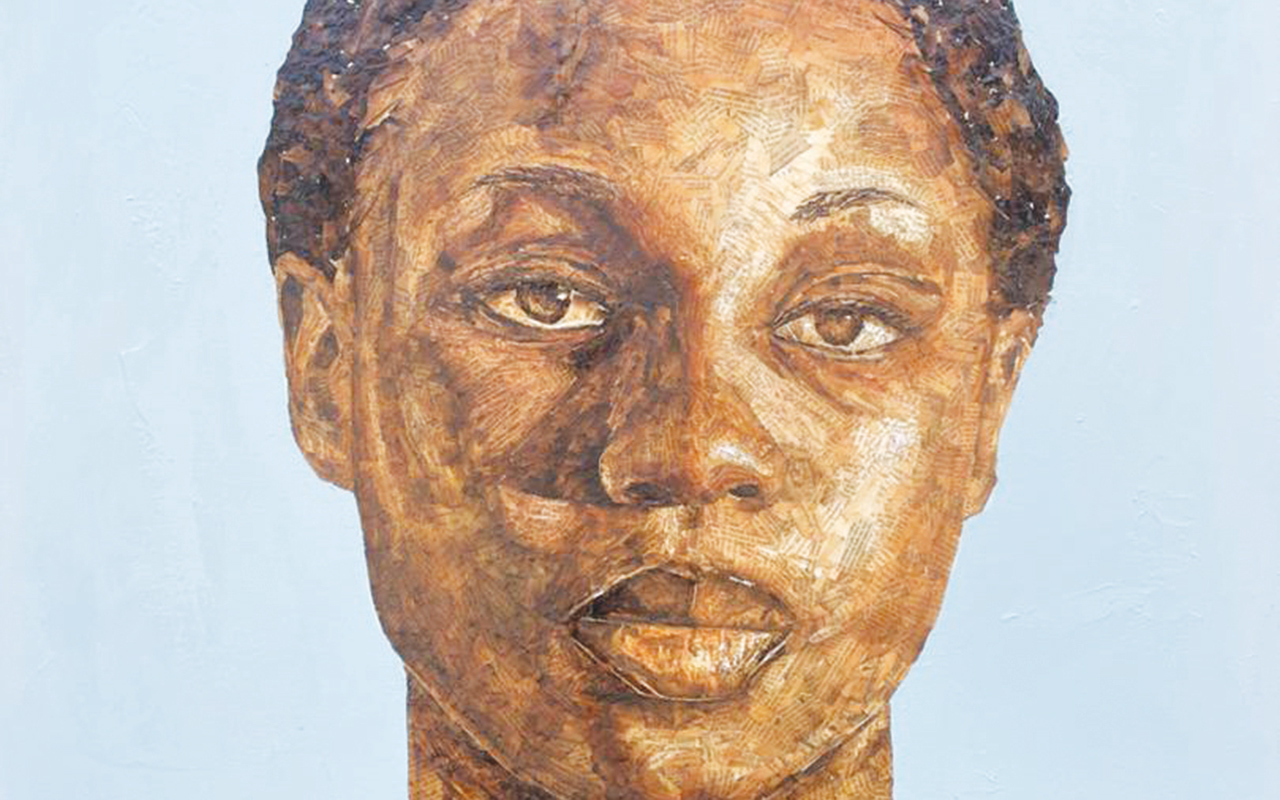

The five exhibiting artists, Chioma Ebinama, Miranda Forrester, Ogunbiyi, Nengi Omuku and Charmaine Watkiss, all women, work internationally.

In the show, they detail the radical circles the woman inhabits and interrogates semi-autobiographical and self-revealing glimpse of a brilliant but fractured matriarchal order.

Materially and collectively, their works draw attention to intimacy, reparative approaches and the valourisation of labour.

Ebinama, who is based in Athens, Greece, engages with animist mythologies and non-western philosophies, and conceptualises her interpretations as drawn and watercolour compositions on rag paper. Her watercolour is lyrical and transformative.

The show features her suspended circular painting, the Bride 2 (2022), inspired by a scene of matrimonial rite, as featured in Chinua Achebe’s 1958 classic novel, Things Fall Apart. This is presented with the audio piece, Prayer for when fear strikes at dawn (2022).

The metaphorically fluidity of her work allows visitors to understand her natural environment in a new way and ensure that the painting is reflexive sequence of the African cosmogony.

Forrester’s work subsists in the worlds of emotions that equal the seriousness that parents, lovers and friends encounter.

Ogunbiyi comes with how commerce, architecture, history and botanical cultures inform the interactions and gestures that inscribe public and private space.

She continues her robust, knotty work of setting down the sinews and resistances of actual life experience. Avoiding the contiguous snares of sweetness, the work transcends the context of social privilege to enter into the high stakes of real life, in which every daughter must learn.

Working across the disciplines of painting, drawing and sculpture, she presents, You will labour to find value anew and Sweet Mother, Mama Ibadan (2022), which honours the dexterity and labour of women.

Omuku presents Candyscape (2022), which adapts her interests in the politico-cultural representations of the figurative body to comprehend the psychotherapeutic impact of landscape on the psyche.

She plunders a range of traditions to do so itself in a manner that tells such story. She brings a pantheon to life and counting rhymes and rhythms of her objects.

Continuing her signature use of silk Sanyan fabric, Candyscape is a large-scale oil painting that momentarily suggests a retreat for the body, to harness the restorative power of real and ideated landscapes.

While Watkiss, another British artist, (UK) is based in London. Her suite of new drawings, Àse (2022) brings Watkiss’ matrilineal deities to Nigeria. These ‘plant warriors’ are the human and spiritual embodiment of medicinal plants and seeds dispersed to the new worlds from West Africa via the transatlantic trade between the 16th and 19th centuries. The deities’ journey is a custodial and reparative rite ceremoniously reminding what flora was taken.

The founder of Tiwani, Varnava, a member of the team of art practitioners, curators, artists and gallerists, who have ushered in a new trend in visual landscaping of Nigeria, explains that the gallery is helping to revitalise the contemporary art scene in the world’s most populous black nation.

She believes that patronage from a pan-African collector base ought to be cultivated, including individuals and organisations.

“I really think we’re navigating through an interesting moment at the time,” says Varnava. “There is such excitement and support around art from Africa and the Diaspora. It is also a time of great speculation.”

This note of caution is understandable. Tiwani Gallery is a commercial enterprise with lofty aims for expansion well beyond its Nigerian venture.

“We need more rigorous support, and for collectors to support older but also a younger generation of artists,” she adds. “That is very necessary for the longevity of this moment.

The lady, who grew up in Lagos, says. “I moved to Lagos from Cyprus when I was 40 days old. I lived here until the age of 11. I grew up around works by Suzanne Wenger, Twin Seven Seven, Bruce Onabrakpeya, Ben Osagie and the like.’’

Upon the completion of her master’s degree in African Studies with a focus on African art at London’s School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), she set up her gallery in Fitzrovia, central London. For her, the location of the gallery was important to the message she needed to convey. Having previously worked with an international auction house, she discovered a weakness in the international visual art scene.

“I thought there wasn’t enough engagement with contemporary material from Nigeria and Africa then. I started researching and talking to people that were interested in publication or exhibition just to introduce to London an additional kind of ‘vibe’ to the art scene,’’ she says.

Her encounter with the late Nigerian curator, founder and director of Centre for Contemporary Arts (CCA), Bisi Silva, in 2008, influenced the birth of Tiwani Contemporary.

“She was instrumental to the development of Tiwani as a whole. She was a great friend and mentor and helped me set up Tiwani in London. And throughout the process of the last 10 years, it was always an open conversation with Bisi when she was still with us and also with my colleagues,’’ she recalls.

“For me, I thought commercially, it would have made sense to establish this in New York or Paris. But then, I feel very close to my Nigerian upbringing. I feel very passionate about the artists I work with and the themes that I want to explore. I feel that if we want to be part of the movement of Africa globally, then we need to be here, talking to local artists and also engaging with local patrons. Basically, I would love to see more works of Nigerian artists.’’

Thus, Tiwani Contemporary has become an institution in Nigeria to help build relationships, convey messages and bridge the gap between artists and collectors both local and international.

WHILE reflecting on her early days at Tiwani Gallery in London, she recalls the hurdles crossed to position contemporary African arts where it is.

“I was an outsider in every single way. I was an outsider in the sense that my production was full of artists from Africa and in the diaspora. Some fantastic galleries were already working with some of them. The October Gallery has El Anatsui but I wasn’t part of the gallery system. I was an outsider because of the geography that I represented. The only way to overcome that was through the quality of the artists that we choose to engage. We have to create the track record through the shows. We had to find the bias and it was a long journey, not an easy one. We also had shortcomings in the early days that we learnt from.

“It was a constant learning process every single day but I think in the past four years or so, things started to feel a lot, I don’t want to use the word easier but smoother. Suddenly we are out chasing clients and now clients are chasing us- so there is a shift. And we have a bigger kind of movement at the moment.”

“If you want to build a truly international collection, we must include Africa in the conversation. Tiwani began to shape things and that led to the creation of an art fair specifically for African galleries. It corrected how art from Africa should be valued.

“People had this idea that just because I worked with artists from Africa, the price of the art should be cheaper or less. But we have helped to break those commercial barriers. Galleries and auction houses are not the best of friends but suddenly, there is a shift in the market and we can see a synergy between the two,’’ she reveals.