Director General of the World Trade Organisation (WTO), Dr Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, said that turning away from open trade would only lead to greater price volatility, inflationary pressures and weaker growth prospects overall.

Speaking at a recent economic policy symposium that had in attendance, global leading central bankers, policymakers and economists, she said predictable trade is a source of disinflationary pressure, reduced volatility, and increased economic resilience whereas fragmentation of trade into rival blocs would be very costly. “A world that turns its back on open and predictable trade will be one marked by diminished competitive pressures and greater price volatility,” she said.

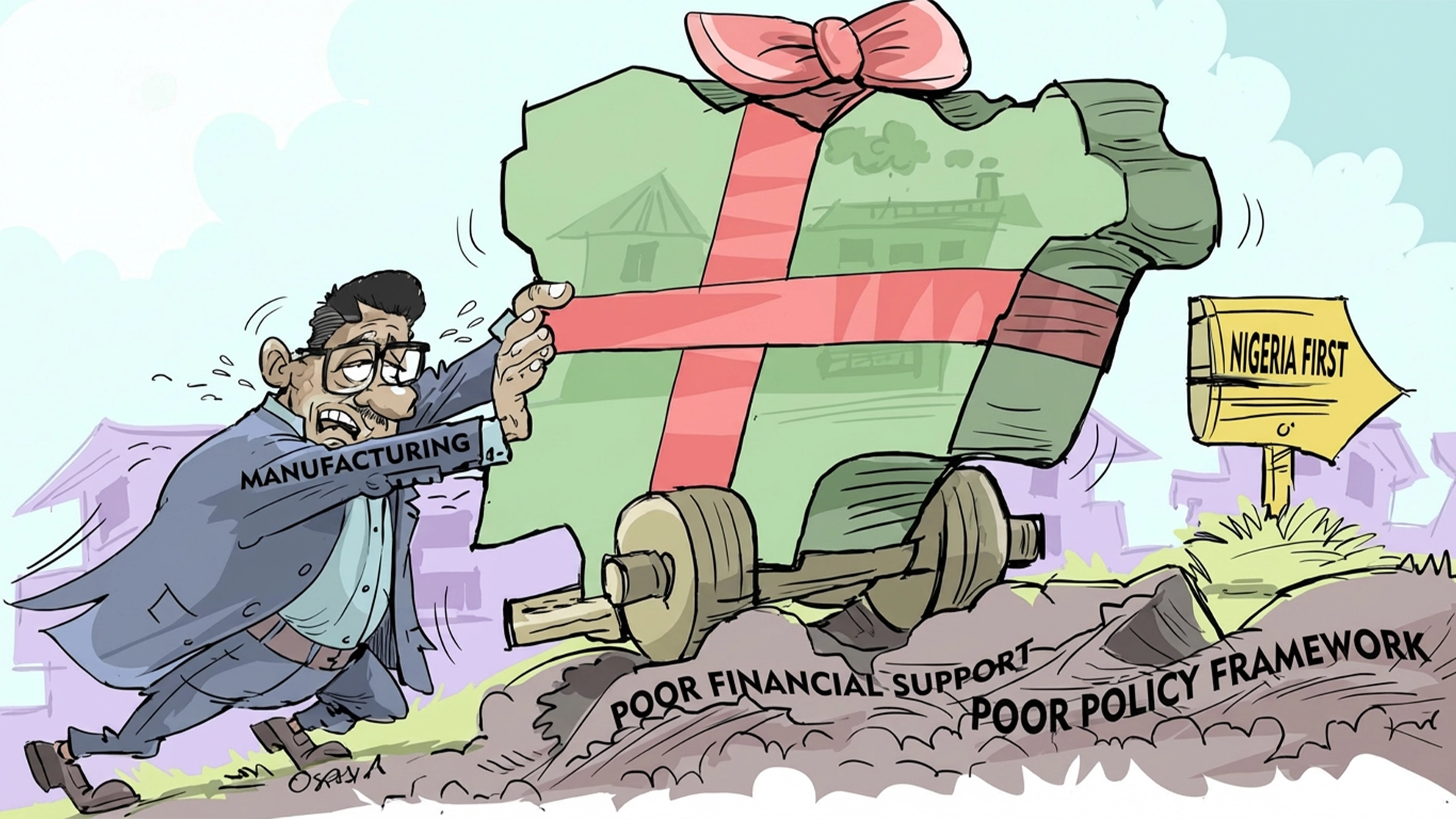

Sustained inflation has made a comeback across the world, with subsequent monetary tightening exacerbating debt distress and financial instability for dozens of developing economies, like Nigeria. Some policymakers have looked at these shocks, alongside rising geopolitical and regional tensions, and concluded that globalisation needs to be rolled back.

However, WTO economists estimate that if the world economy decouples into two self-contained trading blocs, this would lower the long-run level of real global GDP by at least five per cent, with some developing economies facing double-digit welfare losses.

Despite all the tensions and skepticism around trade, overall trade costs for agricultural products, manufactured goods, and services have fallen by 12 per cent over the past two decades, with the increased digitalisation and trade in services potentially becoming a powerful disinflationary force.

‘“Falling trade costs for goods and especially for services mean that globalisation can still be an engine for increased growth, efficiency, and economic opportunities, while also contributing to price moderation,” the DG said.

Increased digitalization and trade in services boosted by initiatives such as the agreement on Services Domestic Regulation, concluded by WTO members accounting for over 90 per cent of global services trade, and the ongoing talks on electronic commerce now being negotiated among 90 WTO members, could become a powerful disinflationary force, she noted.

“Seizing these opportunities requires open and predictable international markets, anchored in a strong and effective rules-based multilateral trading system. Rather than deglobalisation, there is a strong case for diverting some of the energy behind re-shoring to re-globalising production instead,” Okonjo-Iweala noted. She added that evidence of re-globalisation is already visible in countries like Vietnam, Cambodia, Romania, Morocco, and Turkey, all of whom have increased their participation in value chains across a range of goods and services.

“Today, as businesses recalibrate how they think about scale efficiencies versus concentration risks, they have an opportunity to bolster supply chain resilience by taking this diversification process further, to encompass more places in Africa that have good macroeconomic fundamentals but remain stuck on the margins of the global division of labour. Re-globalisation is a far better alternative and I urge us all to embrace open trade, multilateral cooperation,” she said.