The lagoon in Makoko, one of Nigeria’s largest informal settlements, commonly referred to as Nigeria’s Venice, lay so dark it was almost impossible to see the reflection of the sun. The creek’s colour was a reminder of decades of pollution and informal waste disposal that have stained the water.

It was a Tuesday afternoon in late November. The waterway was busy with wooden canoes — some ferrying children, others food sellers and petty traders — gliding through a maze of silt houses.

On one end of the lagoon, a child, no older than 12, splashed through the water with unrestrained excitement. Nearby, adults sat on wooden benches and stools on the floorboards of the stilt houses. Their voices rising and falling, and their sounds mingling with the laughter and cries of children and the sounds of canoes bumping into each other in the narrow waterway.

Here, in a settlement built on water and largely cut off from formal health services, residents frequently treat malaria-like symptoms without medical testing. They rely on patent medicine sellers and unregulated herbal remedies as their first line of care.

Sitting in a canoe at the foot of one of the stilthouses was Sarah Aifoji, a food vendor in Makoko. Sarah was waiting for her 23-year-old daughter, Hannaj Aifoji, who sat in front of a local firewood stove surrounded by wisps of smoke, to hand her the last bowl of food so she could return to hawking.

Sarah, who was born in Makoko and has lived there all her life, said she experiences malaria-like symptoms at least three times a month. Sarah, however, has never visited a hospital to conduct a medical test in the more than forty years she has spent in the community. This life — of self-diagnosis — is the only one Hannah, the rest of her children, and her two grandchildren who live in Makoko, can relate to.

Self-diagnosis is not unique to Sarah or Hannah. Folorunsho Oke, the 31-year-old fashion designer who resides in the stilt house nearby, had only lived in Makoko for five years. Oke said she treats malaria every month, but she has never visited any laboratory or hospital to confirm what it was she had been treating.

Self-diagnosis, self-medication thrive here. Here’s why?

Makoko exists very close to the luxury that is Lagos Island. It is a dense cluster of wooden structures located just underneath the Third Mainland Bridge, and it has existed since the 19th century. The community’s geography has been identified as a key contributor to the frequency of illnesses among residents of Makoko.

A Professor in the Department of Child Health and Paediatrics at the College of Health Sciences, University of Ilorin, Olugbengba Ayodeji Mokuolu, explained that the unique geography — stagnant water filled with refuse — creates ideal conditions for breeding mosquitoes, which in turn breed malaria.

“A couple of factors constitute the major predispositions to malaria. Here, we are talking about the human host who is going to be affected by malaria, mosquitoes that transmit malaria, and the stages of the development of the mosquito, which has to be within some form of stagnant water environment, the larval stages that metamorphose into the breeding of the mosquito, the level of drug use in that community, and climatic factors.

“The interplay of all these factors tends to determine the predisposition and transmission, the intensity of malaria. Although some of these factors may be present, it does not mean the people living there automatically have malaria. If you take a place like Makoko, some of these factors are prevalent, the community is waterlogged, and the people there are of are low socioeconomic class, and I believe the level of access to preventive approaches may be very low, so they may have a slightly more than average increase in the burden of malaria,” he said.

The geographical disadvantage aside, the lack of access to quality healthcare exacerbates sickness and self-medication in the community. Despite its proximity to the more upscale section of Lagos city, quality healthcare is often considered a luxury. The distance to quality healthcare centres and the meagre incomes of the residents shut many out of quality healthcare. As a result, most fall back on patent medicine sellers, also known as chemists, herbs, and private clinics in the community. They also sometimes rely on medical outreaches from non-governmental organisations.

The traditional ruler of Apollo, a Makoko sub-community, Chief Orioye Jephter Ogbubure, linked the lack of access to quality healthcare to administrative neglect on the part of the government. He complained that the community gets marginalised by the political class except during election periods.

“The government does not come to help us. They only use us to vote during elections. NGOs come here for outreaches mostly than the government. When they come, they can donate food, give elders and widows assistance and others. Most people use private hospitals and chemists. When their medical condition is critical, they visit hospitals on the island or in Harvey Road in Yaba,” said Jephter.

The Lagos State Commissioner for Health, Akin Abayomi, did not respond to comments at the time of filing this report.

Residents told The Guardian that the practice of self-diagnosis and medication persists due to the lack of nearby government-funded health centres and the high cost of malaria testing and treatment in private hospitals. The cost of formal healthcare is, as a result, well beyond the reach of many in the community.

One female resident, Seina Loko, said that she has never undergone a malaria test and rarely visits the hospital for treatment because she cannot afford it.

“I treat malaria three times a month. I never get tests done or visit the hospital for treatment because it is expensive. I have three children and even when they have malaria, I don’t take them to the hospital,” Loko told The Guardian.

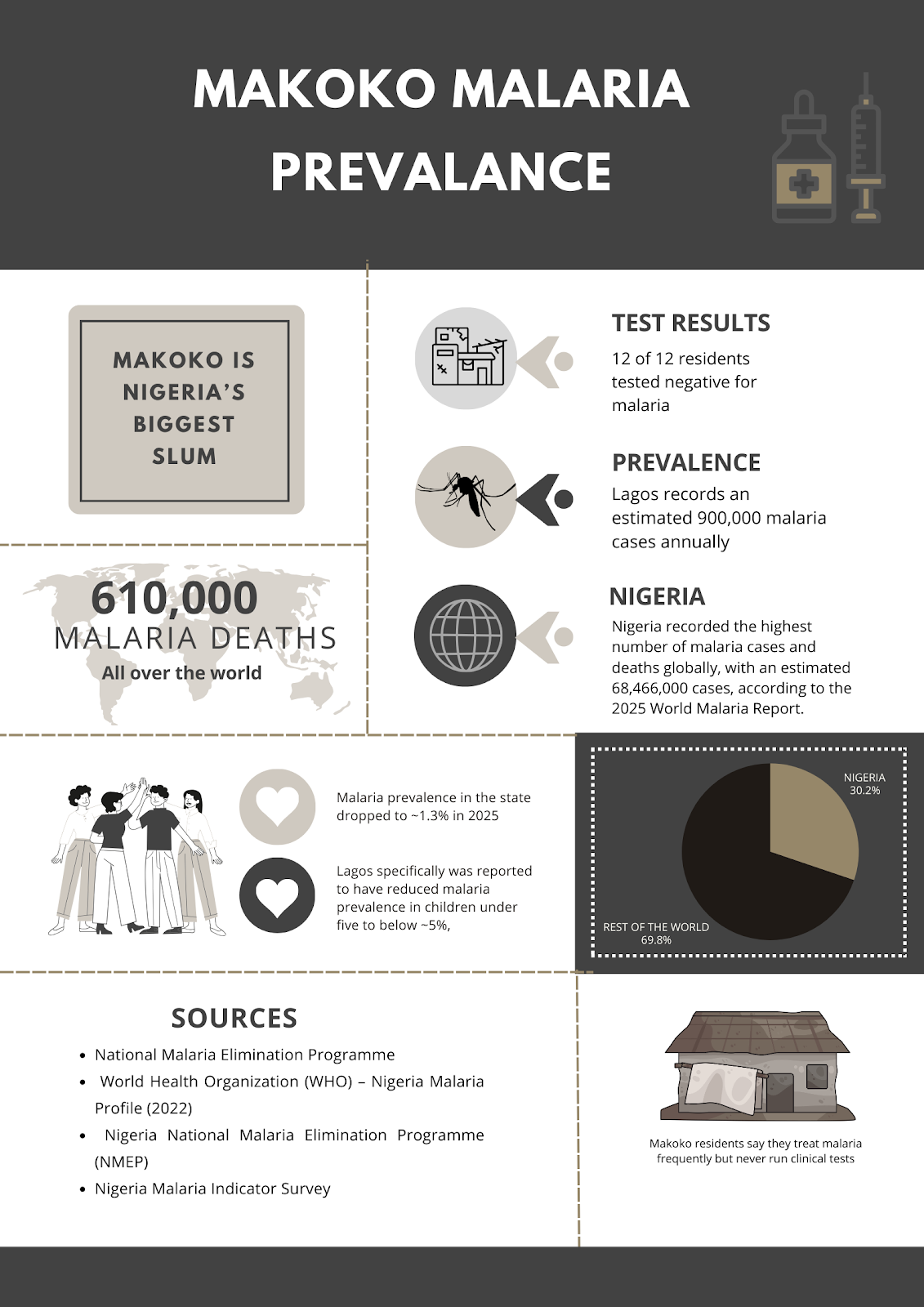

Nigeria already bears the highest burden of malaria in the world, and the conditions in Makoko make residents particularly vulnerable to infection. According to the 2025 World Malaria Report, the country recorded an estimated 68,466,000 malaria cases and accounted for approximately 30.3% of all malaria-related deaths. Of the approximately 610,000 malaria deaths recorded worldwide in 2024, Nigeria accounted for an estimated 184,800.

The Lagos State Commissioner for Health, Prof Akin Abayomi, however, noted that Lagos State, where Makoko is situated, has the lowest malaria prevalence in the country, with an estimated 900,000 cases annually.

Many residents of Makoko, however, claim that malaria is a recurring ailment in the community.

The results of research published in 2023 corroborate the claims of residents. After sampling 100 respondents in Makoko, the results showed that 20 respondents treat malaria weekly, 28 treat it monthly, 15 treat it quarterly, 9 treat it twice a year, 11 treat it yearly, 15 treat it at no specific time, and 2 treat it daily.

Mathew Sunuf, who claims to be a doctor at Minaga, one of Makoko’s privately owned floating health clinics, told The Guardian that the clinic attends to approximately 60 malaria cases per month. While expressing faith in the figure quoted, Sunuf said that the clinic collects blood samples from patients and sends them to laboratories for testing.

“When a person comes in here to complain of malaria, the first thing we do is try to stabilise them by administering drip. We then collect their blood samples and take them to the laboratory to run tests. When the result comes out and confirms the patient has malaria, we administer injection, drip and prescribe medicine for them,” said Sunuf.

An auxiliary nurse who works in a chemist in Makoko, Mahoutin Akissoe, told The Guardian that anti-malarial tablets are the most popular items in her shop.

“Most people who come to purchase medicine request malaria medicine. It sells faster than any of the other drugs we sell here,” she said, pointing to the shelf where anti-malaria tablets were displayed.

In Nigeria, medicine retail outlets, which often sit between street drug sellers and fully licensed pharmacies, commonly referred to as chemists, play a major role in everyday healthcare, especially in low-income and underserved communities, such as Makoko.

They provide easy access to drugs without prescriptions, diagnosis, or laboratory confirmation. For many people, especially in informal settlements and rural communities, chemists are often the first point of care. Patients briefly describe symptoms and drugs are dispensed based on guesswork rather than clinical testing, enabling self-medication, which is often considered a substitute for people who cannot afford proper medical care. This practice is prevalent in Nigeria, and Makoko is no exception.

In Makoko, every illness is malaria

When residents experience symptoms similar to malaria, such as weakness, headaches, and increased body temperature, they often attribute it to malaria. This culture has been emboldened by the unaffordability of quality healthcare, among other factors.

When she spoke with The Guardian, Elizabeth Mehento, a 30-year-old mother of seven and a roasted fish trader, sat in her home in Makoko with her children sprawled around her on the creaky waterboard floor of the house. She recounted when her 11-year-old son fell ill a week after his birth. She said he had fallen ill with malaria, and his condition deteriorated quickly.

“He is the only child I have that falls sick with malaria the most,” she said, pointing at a fair-complexioned little boy who lay on the floor. He attempted to get up, moving his legs, while his head stayed turned in one direction and could not move.

“When he had malaria as a baby, people said evil people inflicted it on him. I went to so many places seeking treatment for him and spent lots of money. I lived in a hospital for a whole year, and this was how he turned out. Everything started with malaria. He does not speak, walk, or sit,” she said.

Natalie Messe, an 18-year-old mother of one, also claimed to treat malaria twice a month. When asked to describe the symptoms she felt during those times, Messe said she experienced weakness, high body temperature and frequent headaches. Other residents The Guardian spoke with said they experience similar symptoms frequently and whenever they do, they consider it malaria.

According to the United States Centre for Disease Control and Prevention, the symptoms of malaria include fever and flu-like illness, chills, headache, muscle aches, and tiredness, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhoea.

Despite widespread belief in Makoko that these symptoms indicate malaria, Professor Olugbengba says the disease cannot be diagnosed without testing.

“We encourage that before you treat malaria, you should get tested. If you begin treatment without getting tested to confirm it is malaria, you could waste precious time waiting to treat the disease to see whether there is no response. risk the condition deteriorating into an outcome more sinister than malaria,” he said.

He added that self-medication carries numerous adverse effects, such as resistance to anti-malaria medicines.

“Most self-treated medications are likely to result in incomplete treatment, and when you do that, you are presenting your blood as a theatre for the emergence of resistance to anti-malarial medicine. It means that when the person now has malaria, the drugs available are no longer going to be effective. And that can lead to rapid deterioration of the patient’s condition.”

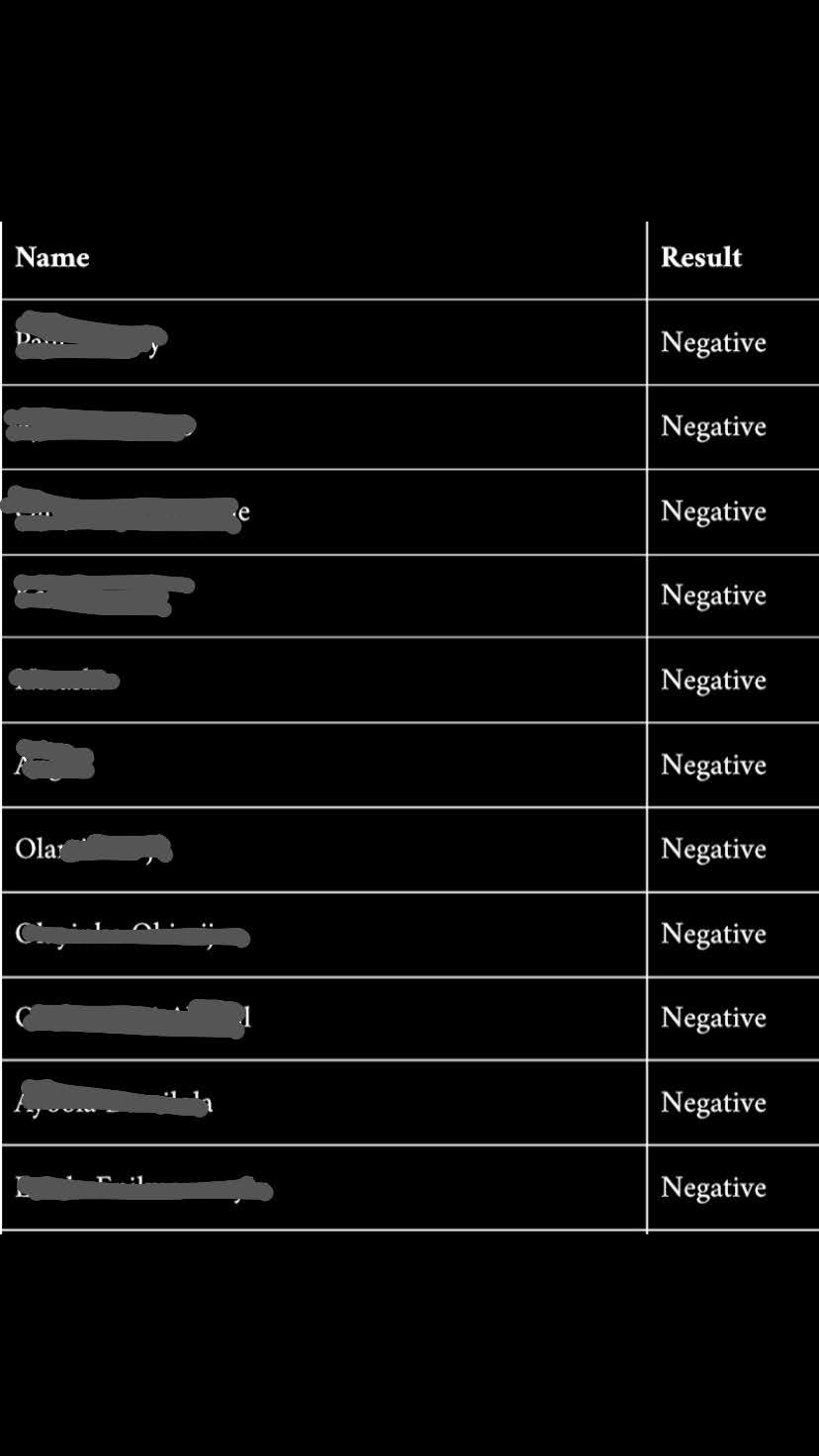

To assess the accuracy of self-diagnosed malaria cases in Makoko, malaria rapid diagnostic tests were administered to 12 residents who claimed to be experiencing the disease and they were tested. Despite reporting symptoms commonly associated with malaria, none of the residents tested positive for the disease.

Among those tested was an eight-year-old boy whose mother said he had been experiencing symptoms she believed were malaria-related for three days before the test was conducted. The result also came back negative.

Reliance on alternative medicine

In the absence of affordable and reliable healthcare, many Makoko residents turn to alternative medicine to treat what they believe is malaria.

Alternative medicine refers to health practices and products used in place of standard medical treatments (such as prescription drugs or surgery), encompassing a wide range of therapies, including herbal remedies.

Herbal mixtures brewed from leaves, roots, and bark are widely sold by local vendors and prepared at home based on generational knowledge and word-of-mouth recommendations.

Ogungbure, the traditional ruler, said that the practice of using herbal remedies to treat malaria in Makoko is an age-long practice passed down from generation to generation.

In conversations with ten residents of the community, each admitted to preparing herbal remedies at home for malaria treatment.

For Lorim Loko, a female Makoko resident who claims to treat malaria weekly, herbal remedies commonly referred to as “agbo” are her first point of call whenever she experiences symptoms similar to malaria.

“I always prepare agbo for myself whenever I am sick. I treat malaria every week.

Her reason for resorting to herbal remedies is the same as other residents who turn to self-medication. They cannot afford treatment costs. More importantly, access to primary healthcare is limited.

Another resident, Maria Zanu, who is in her thirties, told The Guardian that she goes to the hospital occasionally to seek healthcare, but turns to herbal remedies more times than she has visited a hospital for treatment.

“I have lived in Makoko for over 30 years. Despite sleeping under a mosquito net, I still treat malaria frequently. Whenever I notice malaria symptoms, I buy the required herbs and prepare it at home. It is cheaper than hospital treatment,” said Zanu.

All the residents who admitted to using herbal remedies to treat malaria expressed confidence in the efficacy of the remedy in curing malaria. The professor, however, says otherwise.

According to the professor, no herbal remedy has been scientifically proven or tested to cure malaria.

“There is a common belief that herbal remedies can treat malaria because many antimalarial drugs originated from traditional Chinese medicine and later became standard treatments. However, based on the available scientific evidence in Nigeria, I am not aware of any local herbal remedy that has a proven, effective antimalarial impact. This is a scientific position, not a dismissal of ongoing research.

“There is an active field of study called phytochemistry that continually explores which plants may have medicinal properties, including antimalarial effects. Research in this area is ongoing, and it remains possible that useful compounds could be discovered in the future. However, it is important to be factual with the public: at present, there is no herbal medication with a sufficiently concentrated antimalarial active ingredient to be used for curative purposes,” he said.

He added that the infamous neem leaves commonly referred to as “dongoyaro” in Nigeria, which has been described by many Nigerians as the most potent herbal remedy for malaria, does not contain active anti-malaria components needed to cure the illness.

“Even widely known remedies such as dongoyaro do not contain the critical mass of antimalarial compounds required for effective treatment. At best, people are taking suboptimal doses of substances that may appear to have antimalarial effects but are not clinically effective. For this reason, I would strongly discourage the use of herbal medication for treating malaria.”

A researcher and lecturer at the University of Lagos, Stephanie Alaribe, after exploring alternative strategies to manage and treat malaria, made a drink from mango, dongoyaro and African peach and fed it to mice infected with the Plasmodium berghei parasite. The mice were thereafter examined for three possible responses: preventive, suppressive, and curative effects of the polyherbal mixture.

Alaribe noted that at the end of the research, none of the decoctions had completely cleared the parasites, but they all produced substantial clearance. He added that the combination of all the plants could be useful in suppressing malaria in its early stages, but further studies would be required to determine if it would be effective for treating malaria in humans.

While explaining the dangers inherent in relying on herbal remedies for treatment, the professor noted that they could be harmful to the kidneys because the composition of the remedies is unknown. Some research has found that they contain heavy metals (like lead, cadmium, mercury) that are known to damage organs such as the liver when consumed repeatedly.

Parents feed herbal remedies to children

Children also bear the brunt of limited healthcare access in Makoko. Many children born and raised in the community have never set foot in the four walls of a hospital for treatment because their parents cannot afford it. So, when ill, they also undergo the same processes as the adults: self-diagnosis, self-medication and a reliance on herbal remedies for treatment.

Mehento, the mother of eight, confirmed this. Rather than take her children to a health facility for treatment when they fall ill, she relies on it for treatment.

“Whenever any of my children fall ill, I prepare agbo at home and give it to them,” she told The Guardian.

In this community, parents often give herbal remedies to infants as young as six months when they fall ill. Natalie Messe, an 18-year-old mother of a nine-month-old infant, told The Guardian that she administers it to her son whenever she notices any signs of illness.

“I noticed my son developed malaria symptoms in September. I had no money to take hom to the hospital for treatment. I prepared agbo at home and gave it to my son,” said Messe.

The use of herbal remedies is widespread even among pregnant women in the community. Loko recalled taking them during each of her three pregnancies and said she has passed the practice on to her children, the eldest of whom is now 15 years old.

Public health experts have warned against administering herbal remedies to children, citing that they are unregulated by government bodies like the National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control (NAFDAC), meaning there is no guarantee of the ingredients, dosage, quality, or safety, and they can result in severe medical complications.

A US-based paediatrician, Karen Norton, noted that herbal remedies are not a safe health alternative for children.

“The main problem with most herbal remedies and over-the-counter supplements is that they have not been scientifically tested and proven to be effective or safe by randomized, double-blind studies,” Norton noted.

Lagos malaria eradication efforts

Nigeria bears the highest malaria burden globally, accounting for roughly a quarter of all cases and nearly a third of all deaths worldwide, with children under five and pregnant women being the most vulnerable populations.

According to the Society for Family Health (SFH), malaria kills nine people every hour in Nigeria and an estimated 30 per cent of child deaths and 11 per cent of maternal deaths each year are caused by malaria. Additionally, two in every four people with malaria in West Africa are Nigerians.

Nigeria’s Minister of Health and Social Welfare, Prof. Ali Pate, however, noted that malaria transmission is declining in Lagos. According to the minister, Lagos has a positivity rate of less than 5 per cent, compared to 90 per cent in the past, a development he described as an amazing success.

Lagos Health Commissioner says Lagos still records an estimated 900,000 malaria cases annually, with febrile illnesses presumed to be malaria contributing to over 50% of general outpatient visits in public health facilities, despite its low malaria prevalence.

The state government has been able to reduce the state’s malaria burden through community awareness and collaborations with NGOs and private organisations. It also plans to reduce malaria prevalence below 1% through the launch of the Pathway to Malaria Pre-Elimination & Digitisation Program. Makoko residents, however, claim that they receive abysmal support from the government in improving healthcare access in the community.

While Lagos records progress in malaria control, communities like Makoko remain on the margins of that success, where poverty, distance, inequality and exclusion continue to shape health choices.

For Aifoji, Mehento and other Makoko residents, illnesses like malaria are no longer seen as an emergency but as an expectation, treated with whatever their pockets can afford as they cling to the hope that one day quality healthcare will no longer be a luxury.

This report received support from the Thomson Reuters Foundation as part of its global programme aiming to strengthen free, fair and informed societies. Any financial assistance or support provided to the journalist has no editorial influence. The content of this article belongs solely to the author and is not endorsed by or associated with the Thomson Reuters Foundation, Thomson Reuters, Reuters nor any other affiliate.