• President pushing through non-performing budgets repeal, MTEF/FSP, 2026 budget

• Disregards previous poor performances, continues over-budgeting

• Weak, compromised parliament aiding fiscal rascality

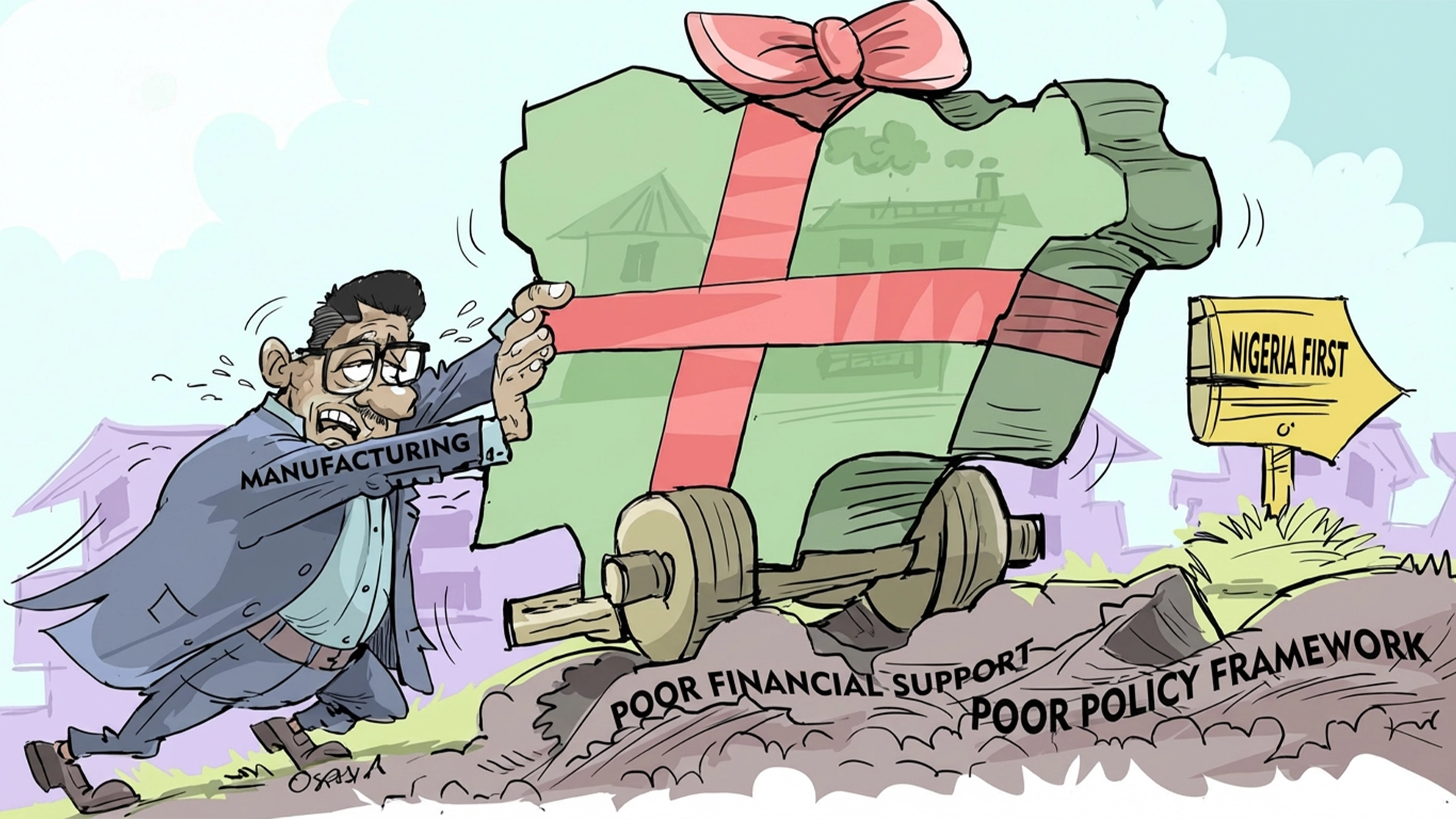

The Federal Government’s budgeting ritual, supposedly a grundnorm of national public financing, has degenerated into a cycle of disorder, fiscal hallucination, politically expedient serial revisions and anything else but empirically supported national resource allocation planning.

At the heart of the crisis is what many have described as an entrenched fiscal rascality, enabled by a weak, complacent, and compromised parliament that indulges in the growing practice of robbing Nigerians of the real benefits of public expenditure, while corroding the entire economy.

The national budget, a document the market had associated with a central instrument of national planning and every citizen religiously looked forward to as a bastion of public trust and hope going into a new year has rather been downgraded into a rolling document of optimistic assumptions and politically convenient alterations even as half-hearted implementation becomes a norm, leaving public finance increasingly exposed to shocks and arbitrariness.

Elsewhere, budget parameters are tested and forged in fire. But the national budget estimates and their benchmarks are not better than mere bets of speculative asset traders, which detracts from the seriousness of national financial planning.

And as the country reels in the consequences of a broken public financing system, President Bola Tinubu is pushing down the throats of the long-compromised National Assembly, which his ruling party has held by the jugular, two supposedly important documents – the 2026-2028 Medium Term Expenditure Framework/Fiscal Strategy Paper (MTEF/FSP), as well as the 2026 appropriation bill.

The former has scaled through the legislative hurdle with literally no value addition. In a matter of weeks, the latter could go the same path.

Thoughtfully crafted as the holy grail of fiscal discipline, the twin documents have become mere rituals. At best, they have been denigrated to articles of trade, advancing the self-serving behaviours of politicians at the seat of power.

Yes, one of the documents has been passed, while the other is expected to secure legislative approval in a few weeks, with no changes exceeding what is required to benefit the lawmakers. Most Nigerians really may not expect anything of substance, in terms of the pursuit of the common good, to come from the legislation.

In between, the President also came asking for a repeal of two budgets that ordinarily should have run their full cycles, giving a hint that the government could strangely muddle the content of three fiscal baskets together going into the new year and compound the budget monitoring crisis and only to create more room for official manipulation.

Tinubu’s budget appropriation re-enactment letter said the action was meant to end overlapping budgets. But the President may have only succeeded in officially calling out the aberration by its name. The content of the letter suggests the opposite of the open claim – legitimising overlapping budgets.

Sadly, the President did little to address many underlying concerns. Does the government intend to extend the 2024 budget beyond its borrowed life (2025)? Does he want to revalidate the acts only to retire them? What about the prospect of muddying up the associated project tracking, monitoring and reporting?

Meanwhile, there was a media report of a circular from the Ministry of Finance directing ministries, departments and agencies (MDAs) to carry over 70 per cent of the 2025 capital programme to next year. So far, there is near-zero knowledge about the operationalisation of the directive and its status in light of the President’s interest in re-scoping the plan.

Last Friday, Tinubu added to the fray when he presented a fresh 2026 spending envelope of N58.1 trillion to the National Assembly to mark another round of what has become a yearly elite bargain rather than a thorough legislative process that should put the feet of the cabinet members on fire.

Until the presentation, there was a strand of rationalisation that the expected 2024/2025 consolidated act could serve the purpose of the 2026 budget to truly end the era of “overlapping budget” – a radical but realistic fiscal option, perhaps.

If the assumptions of the 2026 budget draft are surprising, the chains of events leading to the presentation of the supposedly important legislative document were more intriguing.

The December 16 request for a “repeal/re-enactment” of the 2024 and 2025 appropriation acts is significant. It is the first time a Nigerian president would make such a demand: that two non-performing budgets be reactivated concurrently.

Two streams of thought came from the President’s request. Once, he comes across as a blatantly honest leader. Why pretend when it is obvious the two budgets are on the verge of failing? On the contrary, the action betrays the feel-good posture his administration has maintained over the years and the extent of the fiscal crisis he supervises.

At N21 trillion, the 2024 budget achieved a revenue performance of 80 per cent, relatively better than the previous years. And with N8.56 trillion spent on debt cost, the government brought down the debt service to revenue ratio to a remarkably low 41 per cent in comparative terms.

But that is where it ends. The budget was handed more feathers – with its life stretched across two years – yet it could not fly high in terms of delivering on capital expenditure, which underperformed by 54 per cent. The Federal Government, according to the budget implementation report (BIR), spent a total of N6.37 trillion on capital projects, even with its execution extended till this month, leaving a hole of N7.4 trillion on the appropriated N13.77 trillion.

The running budget may not be better, going by the President’s interim report. As at the end of the third quarter, only N3.1 trillion or 17 per cent of the target was released as capital expenditure, Tinubu told the National Assembly.

Whereas the Minister of Finance and Coordinating Minister of the Economy, had earlier disclosed to the lawmakers that the government was in shortfall of N30 trillion or 74 per cent of its ambitious N40.8 trillion revenue target as at December, the President said the government had realised N18.6 trillion at the close of the third quarter in reminisce of official contradictions the citizens have been regaled with.

The supposed next year’s budget estimates were prepared and presented with the parameters, the hurriedly passed 2026-2028 MTEF/FSP – a document the law says should get to the lawmakers four months before the end of the year, but was only approved by the Federal Executive Committee (FEC) in December.

The Senate had passed the rolling plan on December 16, whereas the legislative process broke down at the House of Representatives over disagreement on the oil price benchmark, some members felt could be more conservative. Eventually, the lower chamber also carved in and allowed the document to go through to starve off further budget presentation delay.

Like the oil price benchmark, which the MTEF/FSP 2026 – 2028 retains at $64.85 per litre, the Federal Government continues to double down on hope, adopting best-case scenarios, which suggest that it rarely learns from the historically wide gap between earned and projected revenue.

Last year, the variance between actual and earned revenue was -19 per cent, which was relatively low compared to the previous years’ average but 2023. In 2022, the government projected N9.97 trillion but earned N8.81 trillion, while the figures were N6.64 trillion and N4.64 trillion, respectively, a variance of -30 per cent. During the eight-year administration of late President Muhammadu Buhari, the variation was as wide as over 40 per cent in some years.

Except in 2023, the government had consistently underperformed its revenue targets, a challenge mostly linked to imaginary benchmarks as opposed to working with more conservative scenarios. Most African countries work with the worst-case scenario when planning their yearly budgets. But Nigeria had done the opposite in recent years.

As of September, assuming the President is correct (Edun has a different figure), the government earned a total of N18.6 trillion, which is 46 per cent of the ambitious N40.8 trillion contained in the 2025 budget.

If the government maintains the same pace, it will end the year with N24.8 trillion as its equity in the N54.99 trillion budget, leaving the deficit (financed and unfinished) at N31.19 trillion. A 57 per cent fiscal deficit is untidy, notwithstanding the considerations.

All other 2026 budget estimate assumptions are equally spurious. Crude is a major anchor of the revenue, projected at N58.18 trillion, but the assumptions are fragile at best, given that Nigeria’s actual oil production and export prices have repeatedly missed targets in recent years.

Whereas the country struggles to meet the 1.5 million barrels per day (mbpd) Oil Producing and Export Countries (OPEC) quota, the government is counting on a daily production target of 1.84 mbpd next year – an ambition already considered unrealistic. A major snap could send the price of oil trading 30 per cent or more below the benchmark $64.85. Already, the price is a significant premium on the OPEC Basket.

The benchmarks of crude, which is driving the numbers, are off what is considered a realistic assumption, which could detract from the prospect of meeting the revenue target (N34.33 trillion). Over 40 per cent markup on the annualised earnings of this year is an ‘oversize’ for a country whose major revenue streams are externally extremely volatile and significantly outside the country.

Other figures are no less troubling. A project deficit of N23.85 trillion, which is over four per cent of the output level, betrays the government’s lack of commitment to fiscal stability and debt sustainability. This gap means the government expects to borrow heavily – a familiar pattern that has eroded the fiscal headroom. The deficit dependence, some experts have said, reflects budget optimism over policy realism.

A debt servicing allocation of N15.52 trillion, 26.7 per cent of the entire budget, a commitment that exceeds the combined planned spending on some critical sectors, increasing concerns about shrinking fiscal space for growth and social investment.